Activities at the Shark Lab

Samuel, better known as Doc, has been studying sharks for 50 years. He discovered how sharks see and even gave us insights into how they think. He founded the Bimini Biological Field Station in 1990, and has been training and inspiring young shark researchers ever since.

I am a fisheries ecologist and avid outdoorsman. I grew up in rural Central Florida, spending much of my childhood at the local beaches and coastal rivers. With a mother who was a marine biology teacher, my interest in marine sciences was fostered at an early age.

A desire for new scenery and wild places took me across the USA to Alaska, where I pursued a career as a fisheries biologist. I worked for several years on large research grants monitoring salmon populations and the effects of invasive northern pike in South-Central Alaska. However, my true passion was working with sharks...

As a child in the late 1940s, I was what we in Miami called a ‘water baby’. I used to go down to the docks and look at every fish that was brought in. While the other kids were playing baseball, I was out there looking for sharks and fishes and walking the beaches for miles, collecting seashells. At age 12 I taught myself to scuba dive, and when I was a teenager we used to sail out to the reefs on an 80-foot schooner and spend the weekend on a reef, feasting on the fish we had speared.

My...

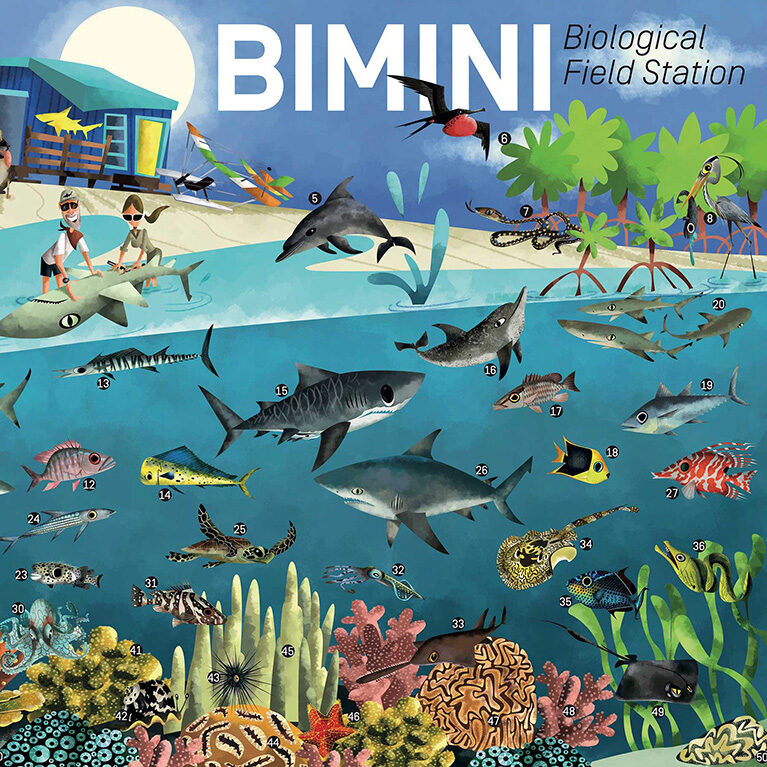

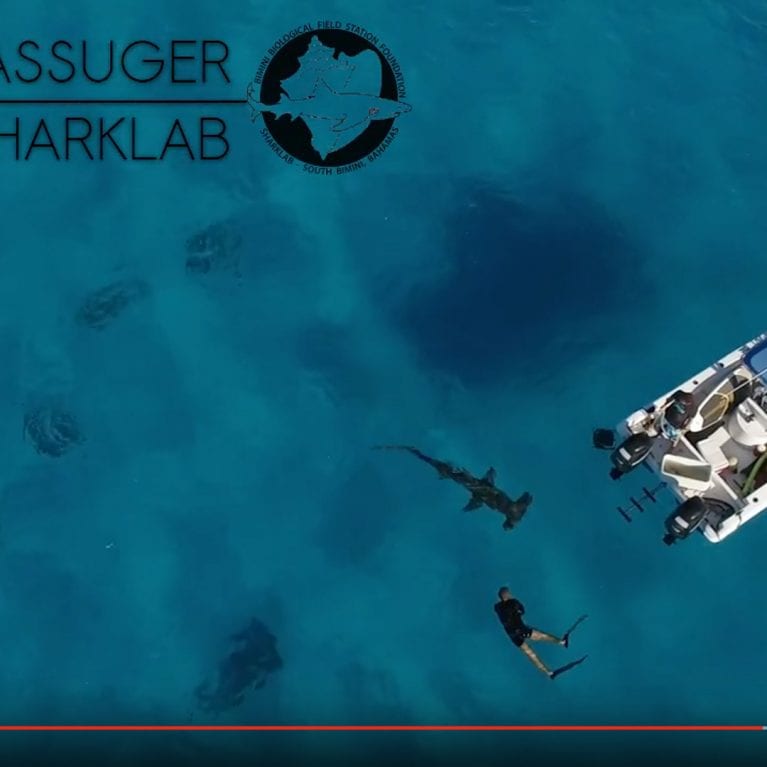

Elasmobranch research, education and conservation in Bimini, Bahamas

The goal of the Bimini Biological Field Station Foundation is to advance knowledge of the biology of sharks and rays, and the role that they play in the marine ecosystem, and to improve their management and conservation as well as enhance public perception and understanding of these fishes.

Adequate conservation and management of shark populations is becoming increasingly important on a global scale with declines documented worldwide. A recent study estimated the total catch and fishing-related mortality for sharks globally was more than 100,000,000 sharks per year. There is an urgent need for the collection of biological information on many shark species, which the Bimini Biological Field Station Foundation aims to address.

The following background information relates to two of our objectives that show the diversity of projects that the Bimini Biological Field Station Foundation conducts. One is pertinent to management and conservation of large coastal sharks, specifically the great hammerhead, and the other harnesses the lemon shark as a model species for advancing behavioural theory and understanding individual variation.

Great hammerhead: a crucial need for spatial data

The great hammerhead shark Sphyrna mokarran is a target or by-catch species in a wide variety of fisheries throughout its range, and substantial population declines are suspected to have occurred in many areas as a result of fishing. The great hammerhead in particular is highly sought after in the international shark fin trade because of its large fins. It has also been added to CITES (Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species) Appendix II and is categorised as Endangered by the IUCN (International Union for the Conservation of Nature) Red List.

A real conundrum for fisheries across the globe is how to reduce capture of hammerheads? Prohibiting retention would not be effective as they have the highest at vessel mortality of any species (about 90%). Thus it is crucial that we understand more about space, habitat use and behaviour of this species. Do they use migratory corridors? Are there spatial hotspots?

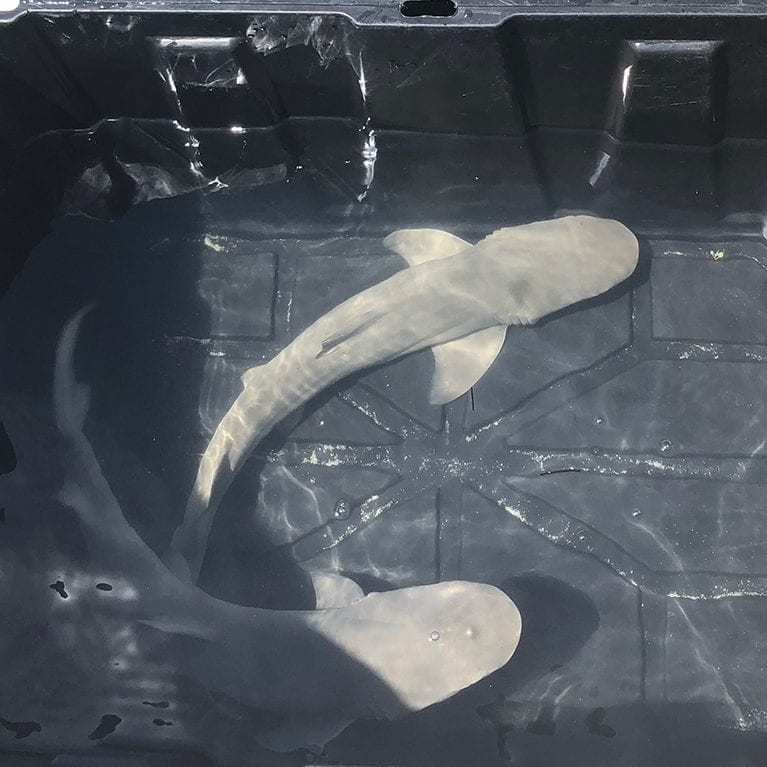

Consequences and cause of personality

Personality differences are widespread throughout the animal kingdom and represent individual behavioural variations that are consistent over time. They determine the way animals react to novel and challenging situations, which can affect resource acquisition, social interaction, survival and reproduction. Personalities have been well studied in freshwater fish. However, despite important ecological and evolutionary consequences, nothing is known about personality variation in sharks and other large marine fishes. Personality variation in apex predators, such as sharks, could have implications for the health of marine ecosystems. The attributes of the lemon shark Negaprion brevirostris system in Bimini allow a range of questions to be explored that cannot be asked of many other wild-ranging animal species. Such as, is personality heritable? How do mortality and growth of juvenile sharks correspond to behavioural types or syndromes? Does this correspondence change over ontogeny and ecological conditions?

Elasmobranch research, education and conservation in Bimini, Bahamas.

Public presentation at MODS: Save Our Seas Distinguished Speaker Series : Shark Research in the Bahamas