How to survive when your mother is a cannibal

Few sharks in the world are as well understood as the juvenile lemon shark, and that is in large part thanks to the extensive work done by Dr Samuel Gruber and the Bimini Biological Field Station on the nursery populations that inhabit Bimini’s coastline. From life history and anatomy, to behaviour and learning, to proving their individual personalities, there is little we don’t know about them. Yet, while we are surrounded by hundreds of these tiny sharks year-round, we very rarely encounter them alongside their adult counterparts. Adult lemon sharks predate on these juveniles, and space partitioning is evolutions way of preventing the species from causing its own decline. But, in a lagoon full of predators, and without these more experienced adult sharks around them, how do these small and naïve animals survive the dangers of Bimini?

Lemon sharks reproduce at the same time every year, which means we know they will predictably return to Bimini to give birth in the Spring. That is exactly what we saw this April, when we were lucky enough to capture five lemon shark pups immediately after their birth. As they wriggled through the water, struggling to orientate themselves, it struck me how vulnerable they seemed. Only 35-65% of lemon sharks will survive their first year of life here. Yet for a species with a conservative life history, maximising survival of pups is of paramount importance. Once we had captured the pups and quickly taken DNA samples and measurements, some of the fascinating ways these newborns are able to adapt became apparent.

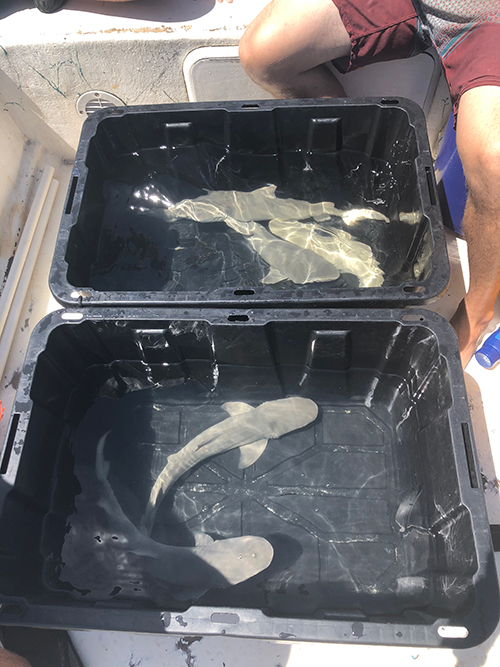

Newborn lemon shark pups. Photo by Clemency White | © Bimini Biological Shark Station.

One of the most noticeable features were their gummy mouths. Lemon sharks come prepared to predate with a full set of small needle-like teeth. But similarly to their dermal denticles and fins, they are uncalcified at birth – likely to save their mother some trouble. This makes them look non-existent, even up close. While we are sure there is no maternal care after birth, the open scar between their pectoral fins tells us that this by no means goes to say there is no maternal investment. Connected by an umbilical cord, up to 18 pups will grow and develop through direct nourishment from the placenta. This ensures that all 18 will be born with good survival chances at a length of 55-65cm, and weighing around 1 kilogram, capable of swimming, predating and surviving alone.

Astonishingly, when we release all five of the pups into the mangrove nursery, where they will develop and grow for the next 13 years before they leave Bimini, they are almost unrecognisable to the sharks we caught just 15 minutes prior. Calcification has occurred rapidly; their teeth are sharper, their fins more robust. Their dermal denticles are now rough and textured and, as we watch them swim off into the tangled roots that will provide them valuable safety, they swim strongly and effortlessly. A stark contrast to the dazed manner in which they swam away from their mother. This quick adjustment is another way that this species has evolved to “hit the ground running” without parental protection.

All five newborn pups being transported to their mangrove nursery. Photo by Clemency White | © Bimini Biological Shark Station.

This is just the beginning for these pups. The lagoon holds extreme temperature changes, an intense tidal range and a multitude of predators that they will have to navigate if not to perish. Yet, while it would be both unlikely and a shame for them to re-encounter their cannibalistic mother, they would certainly have a lot to thank her for in enabling them to survive that long.