Sharks and lasers

My field of vision, already limited by my mask, narrows further as I focus on my camera’s screen through its underwater housing. Having to concentrate so hard means that I am temporarily oblivious to my immediate surroundings, so I’m somewhat startled when I look up from my camera and gaze into the cold eyes of a 3.6-metre (12-foot) great hammerhead shark Sphyrna mokarran. It’s so close I can count its teeth.

© Photo by Chris Bolte

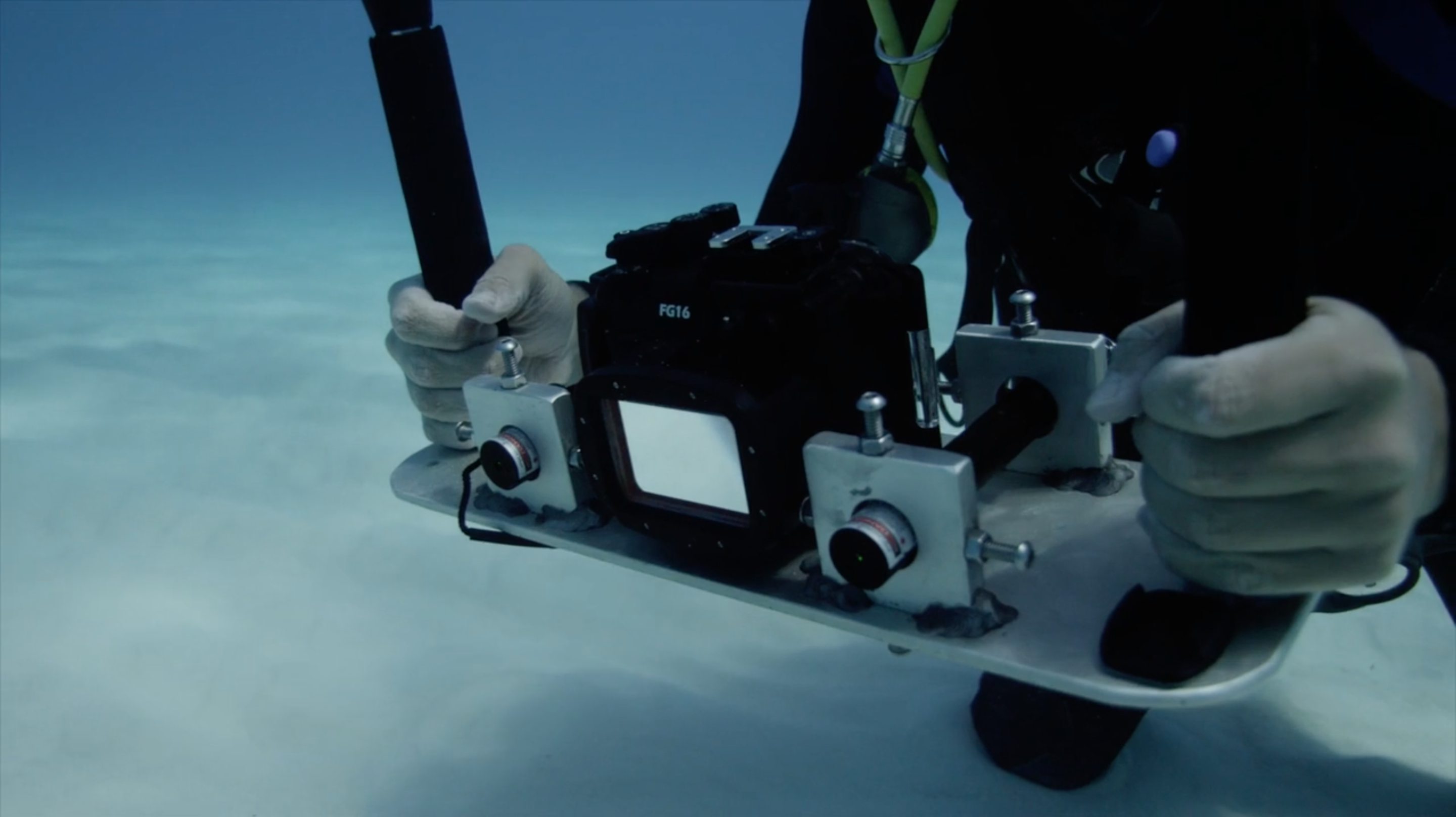

Believe it or not, this is actually a pretty normal winter’s day with the Shark Lab in Bimini and it is a critical component of our great hammerhead research project. These personal encounters enable us to get close enough to photograph the sharks while projecting two parallel laser beams onto their bodies. The lasers, set 20 centimetres (eight inches) apart, can be used to estimate the total length of individual sharks, giving us valuable life-history information. This technique, called parallel laser photogrammetry, has emerged as a simple, non-invasive method to estimate with a fair degree of accuracy the sizes of large marine species such as manta rays, whale sharks and great white sharks – essentially, any animal that is difficult to capture safely.

© Photo by Duncan Brake

In the water next to me, managing the bait-filled container used to attract the hammerheads, is my good friend and colleague Jack Massuger. As the vortex of sharks swirls around him, he remains composed, sifting through the blockade of stubborn nurse sharks to gently coerce the hammerheads into exposing their sides to my camera. If a shark’s side is anything but perpendicular to the twin green beams, it introduces an error of parallax. This means that, due to the angle between the photographer and the shark, the distance between the lasers will change, resulting in skewed length estimates. Getting perfect photos is a process that requires patience. We spend many dives and many hours with the hammerheads.

Using laser photogrammetry, paired with photo identification to distinguish between individuals, we are beginning to learn more about these enigmatic predators. How long are they spending in Bimini? Do they come back every year? Are these individuals sexually mature? Where were they before they came to Bimini, and where do they go when they leave?

© Photo by Duncan Brake

© Photo by Duncan Brake

After a season of data collection, we know that more females visit than males, and many of the sharks are large enough to be sexually mature. Using photo identification, along with acoustic receiver arrays, we have been able to locate sharks that we see in Bimini in places like Key Largo, Virginia and the Bahamas’ Exuma Islands, which has helped to reveal their large-scale movement patterns. Listed as Endangered by the IUCN, the great hammerhead faces strong fishing pressure for its distinct, scythe-like fins. Our goal is to learn as much as we can about the species so that we can use this information to protect individuals wherever they travel.

© Photo by Bimini Shark Lab

As dusk falls and the light begins to fade, the dive feels like a scene from a science-fiction horror movie. Sharks emerge from the darkness, continuing to circle around us. Two bright green laser beams slice through the water as we record a few more measurements, persisting until it’s too dim to continue. As our air dwindles, we take a final few rasping breaths through our regulators and slowly ascend. It is calm, oddly serene to have these sharks pass within centimetres of us, elegant in their slow, rhythmic swimming. As I shut down the lasers and pass my equipment up to the boat, I can’t resist looking down one last time. Hammerhead sharks pass beneath us and then, one by one, begin to disperse. These laser measurements are important for our research and conservation, but there is something else, something sublime, about just watching these sharks fade gently into the sanctuary of the dark, blue water.

© Photo Bimini Shark Lab

To keep up to date with Bimini Shark Lab, follow us on Facebook, Instagram or Twitter.