Baby sharks sharing space

Sharks don’t look after their babies, but they do choose a safe place to give birth. Ornella’s studies young blacktip reef and sicklefin lemon sharks in St Joseph’s lagoon to see how they get along while growing up together.

While a humpback whale and her calf surface for air, majestic killer whales chase their prey, a pod of dolphins plays in front of a stunning sunset and several shark fins mysteriously break the surface of the waves.

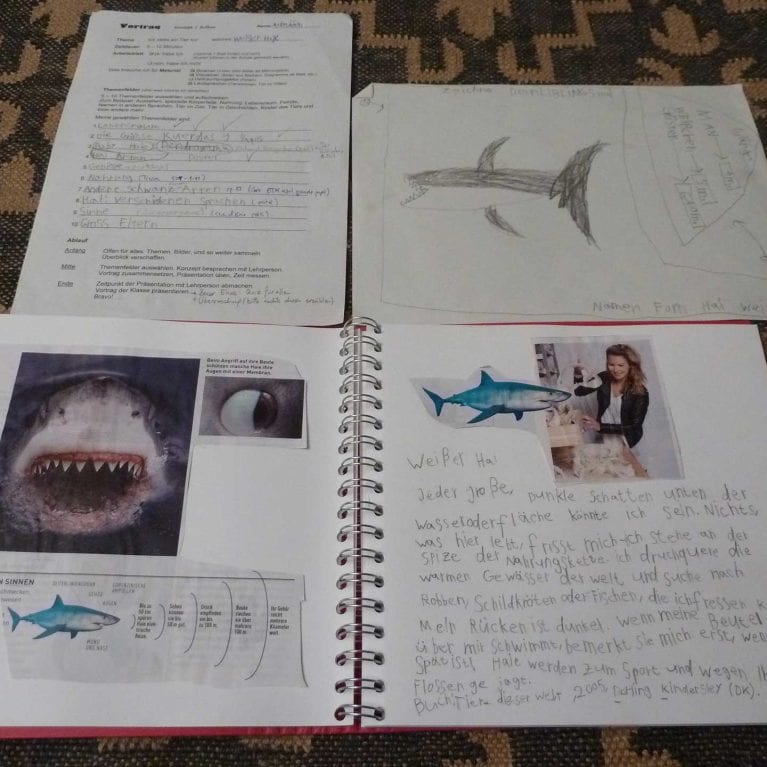

No, this is not a gaudy daydream, but an image of the ocean my young self created while growing up in landlocked Switzerland. Countless drawings like this from my childhood depict my early fascination for marine life, especially the large mammals. Years later, I am a doctoral student working passionately with sharks and I wonder why...

Habitat and resource partitioning of juvenile sharks and their roles in remote coastal ecosystems

To conduct an initial assessment of populations of sicklefin lemon and the blacktip reef sharks in a remote coastal ecosystem and investigate how natural resources are partitioned between and within these species. These findings will be crucial for general management and conservation strategies of juvenile predators in this and other nursery habitats.

Global increases in fishing pressure, habitat loss and biological vulnerability of sharks has resulted in steady population decline. Many shark populations lack baseline data, hampering their management and conservation. This research will add to our understanding of sharks in remote coastal ecosystems.

The sicklefin lemon Negaprion acutidens and blacktip reef shark Carcharhinus melanopterus are both known to live in coastal habitats and atoll lagoons throughout their lives; juveniles of both species show a high degree of site-fidelity to only a restricted portion of these habitats, known as nurseries. Juvenile sharks benefit from the protection and food provided by these nurseries until they reach a certain age when they disperse from their natal home.

For a long time it was believed that young sharks living in undisturbed nursery habitats were able to feed and grow with little to no competition, because it was assumed that the nurseries provided more than enough food for the inhabiting species. But more recently, studies in coastal nurseries have demonstrated that juvenile sharks have high mortality rates coupled with slow growth rates, which is most likely at least partially attributable to an uninvestigated lack of food. Aiming to validate this assumption, various studies have demonstrated that a coexistence of shark species in limited coastal habitats relies on the successful partitioning of naturally occurring food resources or spatial segregation.

Furthermore, resource and niche partitioning is not necessarily restricted to the population level, but can also occur among individuals within a population. This intraspecific variation facilitates the successful coexistence of individuals of one species.

The lack of studies originating from the Seychelles to date, coupled with the rising interest in the roles and importance of predators in coastal nurseries for management and conservation strategies, prompts research with multidisciplinary methods. Such research should include movement data and dietary investigations (of stable isotopes and stomach contents) in order to fully understand the ecology and biology of these predators.

The aims and objectives of this project are to:

- Assess population structure, abundance, life history traits, survival rate, growth rate, reproductive growth and genetic relatedness (60 samples) of the sicklefin lemon Negaprion acutidens and blacktip reef shark Carcharhinus melanopterus.

- Determine home range size, degree of site fidelity and spatio-temporal movement patterns.

- Examine stomach contents and take tissue samples to determine resource partitioning between species and whether intraspecific variation exists.