International Sawfish Day

Illustration by Jamy Silver | © Save Our Seas Foundation

Each year on 17 October, we celebrate the curious group of rays called sawfishes. With their serrated, blade-like snouts that we call their “rostrum”, and their tall dorsal fins and low-slung bodies suited to cruising the seafloor, these extraordinary fishes make our seas the otherworldly place at which we all marvel.

On the flattened underside of a sawfish, you’ll find their nostrils and gills, and in their mouth, the domed teeth that grind the crabs and small fish they eat. And what about that odd “chainsaw” on their head? The rostrum is used to sense, stun and manipulate prey in the murky waters of their preferred habitat.

Illustration by Jamy Silver | © Save Our Seas Foundation

There are five different species of sawfish, and all tend to live relatively long (anywhere between 25 – 30 years, but each species is different). They reach sexual maturity late (around 10 years for some species) and the largest species can grow up to 7 m long.

Why Is There A Sawfish Day?

All species of sawfish are classified as Endangered or Critically Endangered, which means that they face a serious risk of extinction in the wild. International Sawfish Day is used to highlight their wonder, their role in keeping our ocean ecosystems healthy and balanced – and the threats they face, so that we can collectively work to make sure we never lose these rapidly disappearing titans. These slow-breeding, long-lived creatures are fished for their valuable fins that are illegally traded in international markets. Their rostra see them frequently tangled in fishing gear like gillnets and trawl nets, and their habitats continue to disappear as we build on and convert coastal areas around the world.

Illustration by Jamy Silver | © Save Our Seas Foundation

What Is Being Done To Help Sawfishes?

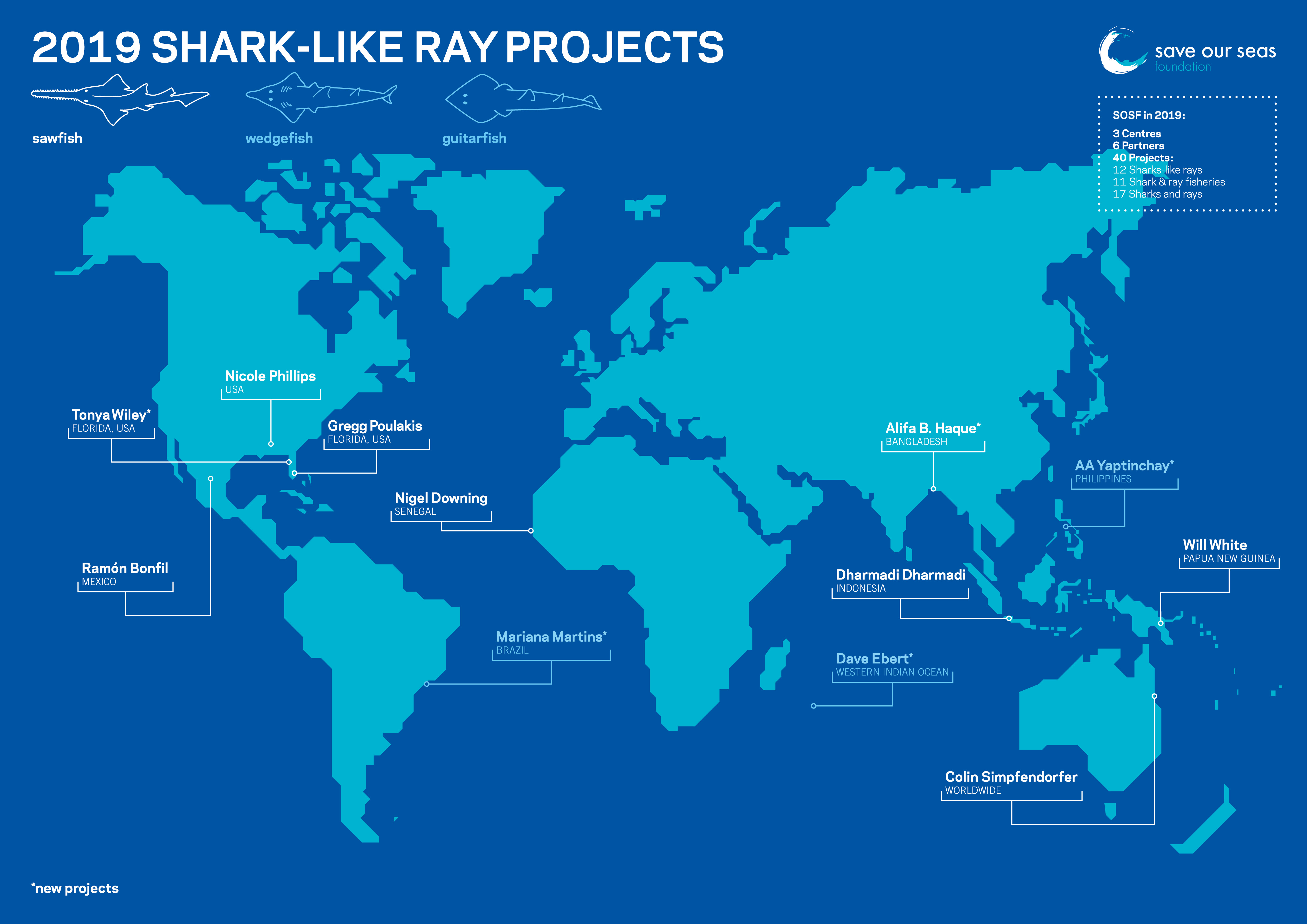

The Save our Seas Foundation has prioritised supporting sawfish research and conservation since at least 2012, recognising that until recently, this was considered the most threatened group of fishes in the sea. Their status hasn’t improved; rather, the plight of guitarfishes and wedgefishes has worsened so that they are now the group of rays closest to the brink of extinction.

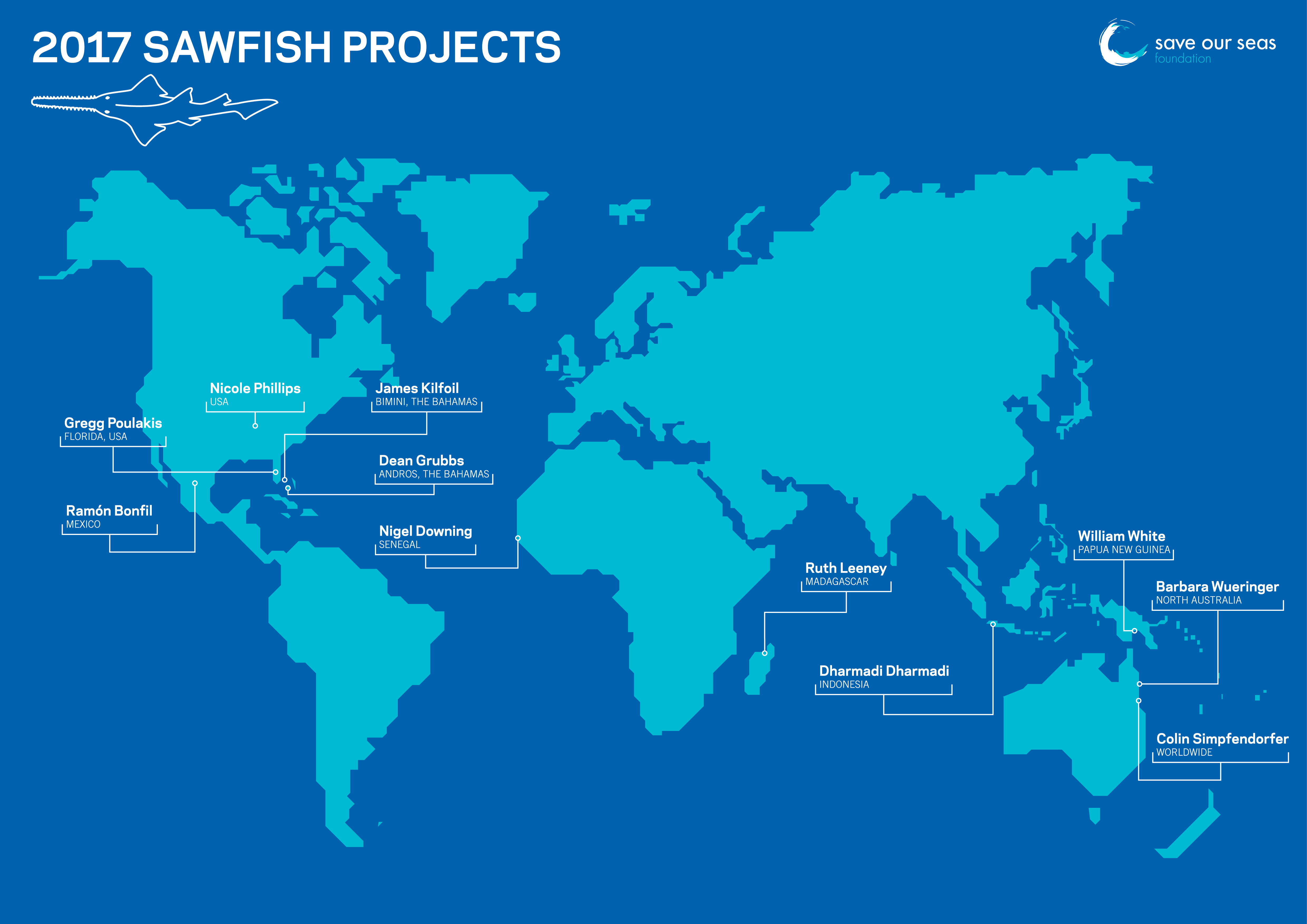

You can follow the work of project leaders in Africa, Asia, Oceania and Central America who have been breaking conservation ground in some very under-resourced areas. Ramón Bonfil is using new technologies and a multidisciplinary approach to find and eventually protect Mexico’s smalltooth and largetooth sawfishes. Armelle Jung has focused on West Africa where the AfricaSaw team developed reporting networks in coastal communities, encouraging them to report sawfish catches. Ruth Leeney searched for sawfish rostra to show that sawfish are still present in at least two river systems, and are at serious risk from gillnet fisheries, in Madagascar. More than 40 years since discovering a shark and ray nursery ground in Senegal, Nigel Downing is returning to investigate if indicators that the sawfishes in the region are all but extinct are true. Alifa Haque is training local fishers in Bangladesh to help map where these four Critically Endangered sawfish species were found and what habitat is essential for their survival today. William White hopes to identify where sawfishes can still be found in Papua New Guinea and how they fit into the local culture and economy. Barbara Wueringer looked at the role of largetooth sawfish in Northern Australia’s waters, and worked with citizen scientists to highlight one of the species’ last strongholds. Dharmadi is running a baseline study to assess where sawfishes can be found and how many are left in Indonesia.

In the USA, Gregg Poulakis is using environmental DNA (eDNA) to track smalltooth sawfish in Florida to determine whether they still past nursery areas and learn about their range and whether it is expanding. Tonya Wiley is searching for clues in Tampa Bay, the first known place where recovering smalltooth sawfish populations would extend their range north.

By analysing rostrum samples from around the world, Nicole Phillips is investigating the genetic health of largetooth and green sawfishes and will estimate how much genetic diversity was lost during the declines sustained by these species. Colin Simpfendorfer is working with sawfish experts around the world to undertake a global sawfish survey using environmental DNA (eDNA). Sonja Fordham has also worked over the years to improve national, regional, and international policies for sawfishes (and other sharks and rays), using scientific evidence to advocating for limits on shark fishing and trade.

What Can You Do To Help Sawfishes?

You’re well on your way already, by simply having read more to educate yourself about the issues. Share your newfound knowledge – with family and friends, at school and at work, and use that to voice your support for sawfishes by lobbying your government to enforce protection measures and uphold the international agreements they’ve signed (like CITES and CMS). You can support science-based conservation in your country, like the expansion of protected areas, and keep your friends accountable to fisheries regulations by being a responsible seafood consumer and ocean-user.

Saving sawfishes sounds complicated, especially because the challenges to their conservation differ from country-to-country. It is definitely complex, but there are many ways you can help. After working for years in Mozambique, Madagascar and Papua New Guinea, Ruth Leeney advises that a smart move will be to support organisations working in low-income countries through donations, helping them to continue their focused and informed work on-the-ground to address local issues. These organisations spend years getting to grips with relevant challenges and suitable solutions, but the lack of resources in these regions holds them back from implementation. Governments, she adds, need to provide livelihood alternatives for coastal communities and reduce their reliance on fisheries. You can petition your own government to clamp down on the illegal trade of fins from protected shark and ray species.