Four years on, are we saving sawfish?

Four years after the first sawfish conservation strategy was released, what have its impacts been so far? SOSF project leader Ruth H. Leeney of Protect Africa’s Sawfishes provides an overview of the many sawfish projects supported by SOSF since the strategy’s release and assesses how far we have come.

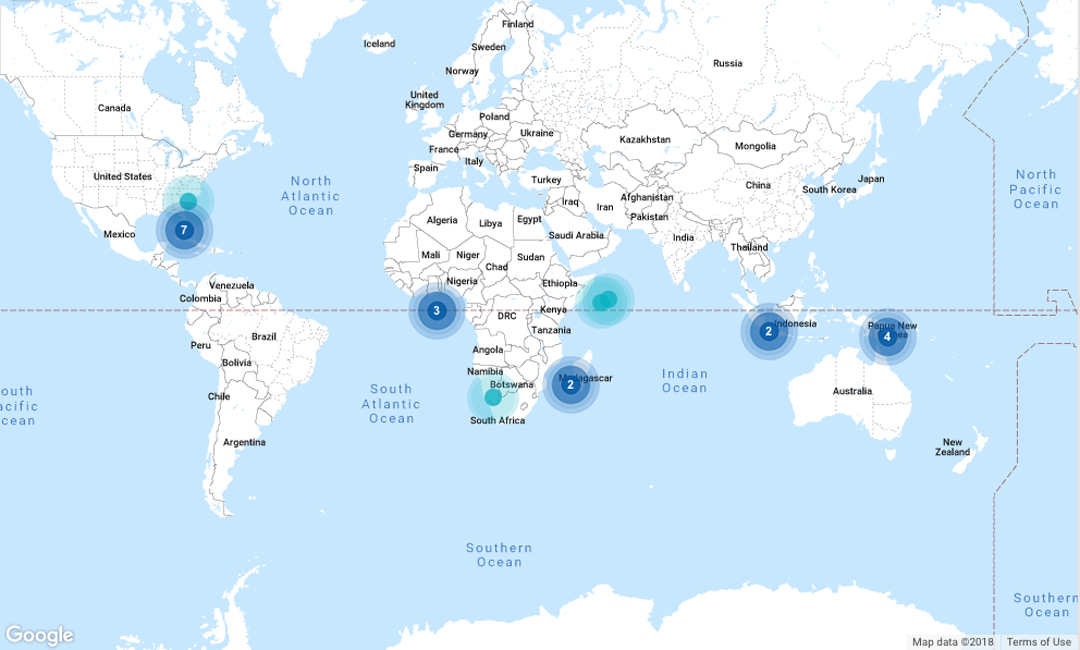

A global map of the locations and number of Save Our Seas Foundation funded sawfish research projects in the region.

(Click here to view the interactive map.)

The first Global Strategy for Sawfish Conservation, the result of a collaborative workshop involving many shark researchers and policy makers in 2012, shone a spotlight on the critical state of the world’s sawfish populations. Published in 2014, it called for national and regional actions to prohibit intentional killing of sawfish, minimise mortality of accidental catches, protect sawfish habitats, and ensure effective enforcement of such safeguards, strategic research and responsible care in captivity. The Save Our Seas Foundation (SOSF) supported the development of this strategy and, inspired by its compelling message, decided to make sawfish a priority for funding. Since then, SOSF has invested more than US$ 650 000 in 13 research and conservation projects to gather data and educate the world about this critically endangered family of fish. SOSF’s tribe of sawfish researchers and advocates have a truly global distribution, with dedicated efforts taking place in Mexico, USA, West Africa, Madagascar, Indonesia, Australia and PNG, and several projects with global scopes.

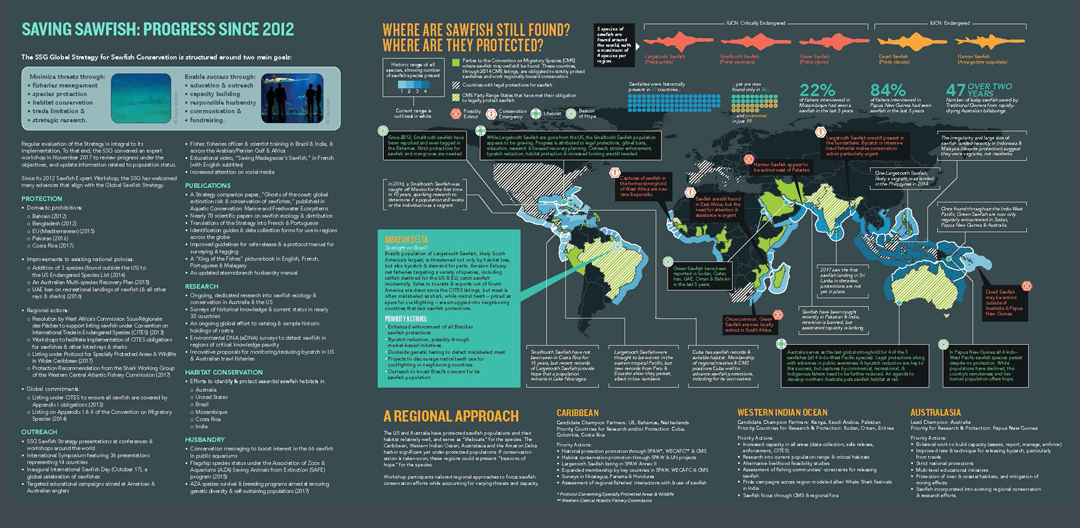

Image © IUCN Shark Specialist Group

Saving Sawfish - Progress and Priorities' - a brochure issued by IUCN Shark Specialist Group in June 2018, summarises the progress made so far for sawfishes, and the research and conservation priorities for the future. Image © IUCN Shark Specialist Group

(Click here to go to the Progress and Priorities website)

In light of the IUCN Shark Specialist Group’s recent release of ‘Saving Sawfish – Progress and Priorities’ – an update to their strategy – we celebrate the efforts made by all of the SOSF grantees focusing on sawfishes, and highlight some of their achievements in the past four years.

Sawfish strongholds

Back in 2014, researchers had already established that sawfish populations were present in Florida, the Bahamas and Australia. These have been termed ‘lifeboats’ for sawfishes – areas where researchers and conservationists hope sawfish populations have the best chance of recovery. Research in these regions has been able to focus on more detailed questions about sawfish ecology, population structure and conservation status. Gregg Poulakis and his research team have been collecting water samples in Florida, from which they extract environmental DNA (eDNA) to learn which habitats are used by smalltooth sawfish. Dean Grubbs and his colleagues have been studying sawfish habitat use in Florida and the Bahamas for eight years, aiming to determine where adult sawfish mate, where the females give birth and where important nurseries are. When they caught an adult female sawfish in 2016, off the remote island of Andros, they documented on film the live birth of sawfish pups in the wild – a world first which proved that that in addition to southwest Florida, the Bahamas is also a pupping area for smalltooth sawfish. The adult female sawfish was satellite tagged and travelled at least 385 km over the course of the following year, providing the first evidence of long-distance migrations by smalltooth sawfish in the Bahamas. James Kilfoil is also working in the Bahamas, assessing whether drones can be used as a non-invasive way to conduct aerial surveys for sawfish. Off Australia’s Cape York Peninsula, Barbara Wueringer works with citizen scientists to investigate the role of sawfishes in the region’s coastal and estuarine ecosystems.

The groundbreakers

In contrast to Florida, the Bahamas and northern Australia, even as recently as 2012, next to nothing was known about sawfish abundance and distribution in many parts of Africa, Asia, Central and South America. Thanks to SOSF support, numerous research teams have been venturing out into the field and, for the first time, describing previously-undocumented sawfish populations and habitats which may be in need of protection, as well as those where, more soberingly, sawfishes are now seldom seen. This less-than-glamorous work in remote areas with challenging conditions, and sometimes without any sightings of sawfishes at all, takes a special kind of commitment.

Ramon and his team enjoy some magical moments in the middle of a stream completely covered by mangrove canopy. They aim to sample every possible sawfish habitat. Photo © Ramón Bonfil

In Mexico, Ramon Bonfil and the Proyecto Pristis México team have been conducting drone surveys of potential sawfish habitats, as well as collecting water samples which will be analysed for eDNA. Ramon aims to identify areas still used by sawfish – information critical in the development of local conservation strategies. The team’s education and outreach work with fishing communities meant that when a fisherman caught a smalltooth sawfish in January 2016, it was reported to Ramon. This was the first known capture of a sawfish in Mexican waters for several decades, suggesting that there may still be a remnant population using Mexico’s Caribbean coast. Armelle Jung and I have both conducted baseline assessments for sawfishes on the African continent. Armelle’s work has been focused in West Africa where the AfricaSaw team have developed reporting networks in coastal communities, encouraging them to report sawfish catches. She has conducted interviews to better understand whether sawfishes are still encountered by fisherfolk. My research in Madagascar has likewise used interviews and searches for sawfish rostra (saws) to reveal that sawfish are still present in at least two river systems, and are at serious risk from gillnet fisheries. I also developed an educational book, ‘The King of the Fishes’, with SOSF support and over 4,000 copies have been distributed to fishing communities throughout Madagascar and Mozambique. Nigel Downing is assessing whether sawfish are still present in southern Senegal, whilst William White is documenting the presence of and fisheries for sawfishes around Papua New Guinea. In Indonesia, Dharmadi and the ‘IndoneSaw’ team are likewise collecting baseline data to establish whether sawfishes are still present, and encouraging fishing communities to release any accidentally-caught sawfishes alive.

Ruth Leeney has distributed French, Malagasy and Portuguese versions of the educational book 'The King of the Fishes' in fishing communities throughout Madagascar and Mozambique. Photo © Joca Faria

Global scope

In addition to these site-specific projects, several projects have a broader reach. At the University of Southern Mississippi, Nicole Phillips and her research group are analysing samples of sawfish tissue from around the world, often taken from rostra in museum collections, to estimate how much genetic diversity has been lost during the declines sustained by sawfish populations. Colin Simpfendorfer aims to resolve the current global distribution of sawfishes using eDNA survey techniques. SOSF has also supported Sonja Fordham’s work to advance sound national, regional, and international policies for sawfishes (and other sharks and rays), by advocating for science-based limits on shark fishing and trade, protection for endangered species and stronger bans on finning.

A diver off of the coast of Florida is dwarfed by a critically endangered Smalltooth Sawfish.’ Photo © Michael Patrick O’Neill

What’s next for sawfishes?

Since the publication of the first Global Strategy for Sawfish Conservation in 2014, sawfish research and conservation activities have spread rapidly to cover new parts of the globe and have uncovered important information which in some places, gives hope and in others, paints a clearer picture of demise. A lot remains to be learnt about sawfish biology and ecology but, in many countries, we will never have the opportunity to do so if we do not first protect the remaining sawfishes from any further decline. Whilst sawfishes are already well-protected in Florida, the Bahamas and Australia, many developing countries do not have any legislation pertaining to sawfishes and of those that do, most lack the resources or capacity to enforce those laws. Simply put, conservation of sawfishes in the developing world will require a different tack. A multi-pronged approach to educate communities on why protecting sawfishes is important and how it will benefit them; assess the socio-economic importance of sawfishes and the willingness of fishing communities to change their behaviour; develop viable alternative livelihoods for communities and encourage community-led strategies for managing sawfish catches, is more likely to be successful.

A Smalltooth Sawfish entangled in fishing gear off the coast of Florida. Photo © Michael Patrick O'Neill

Why are these conservation strategies important?

The Global Strategy for Sawfish Conservation raised awareness amongst not only the research community but also the broader conservation community and the public, of the precarious state of sawfish populations globally. The impressive collation of historical reports to generate a basic understanding of past sawfish distribution revealed huge holes in our collective knowledge of sawfishes; astounding given their huge size, their coastal habitats and their importance in traditional cultures around the world. This catalysed the development of many new research projects, and funding bodies found more than ample justification for the many applications they received, in the strategy document.

Whilst the surge in sawfish-focused research has been remarkable, some baseline assessments (such as those I conducted in The Gambia and Guinea-Bissau) have indicated that sawfishes may now be too rare for any recovery attempts to be successful. Given how many other marine species are in need of research and conservation efforts, and our constant battles as researchers, conservationists, advocates and educators to fund our work, it is important that we identify places where further resources and research efforts will be likely to have a positive outcome for sawfishes, as well as those areas where sawfishes realistically have little chance of recovery, and set priorities accordingly. At the same time, it is essential not to write off areas in the developing world, which face significant challenges for conservation but which are, after all, the areas where much of our planet’s remaining biodiversity is found.

Save Our Seas Foundation is proud to have supported a number of projects that have added many previously missing pieces to the jigsaw, providing novel information that contributes to a far better understanding than we have ever had before, of where sawfishes exist, the threats they face, and how we can address those threats. Armed with that knowledge, let’s continue to empower researchers, educators, advocates and communities to celebrate these unique animals and protect them, and their habitats, for generations to come.