Deep-dwelling and little-known

As pressure on marine resources increases, fishers have to explore deeper and deeper waters to make a living. What does this mean for Belize’s deep-sea sharks? Ivy aims to understand the threat to these animals, before it is too late.

If you ask anyone who knew me as a child, they will probably tell you that all I ever wanted to be was a marine biologist. Other than a short-lived dream to be a ‘marine biologist artist’, I never grew out of my infatuation. I grew up landlocked in Louisiana and Arkansas, but every summer my family rented a beach house in Dauphin Island, Alabama. That week at the beach was one of the highlights of my youth and I can remember noting the annual changes in our crab traps, sea trout catches and the beach erosion as time passed....

Characterising the emerging deep-water shark fisheries in Belize

This project’s key objective is to establish a baseline for deep-water shark species in Belize to underpin their precautionary, science-based management. The data collected during this project will be used to highlight the existence of deep-water sharks among Belize’s public and provide a baseline of abundance, diversity, life history and preferred habitat information prior to overexploitation.

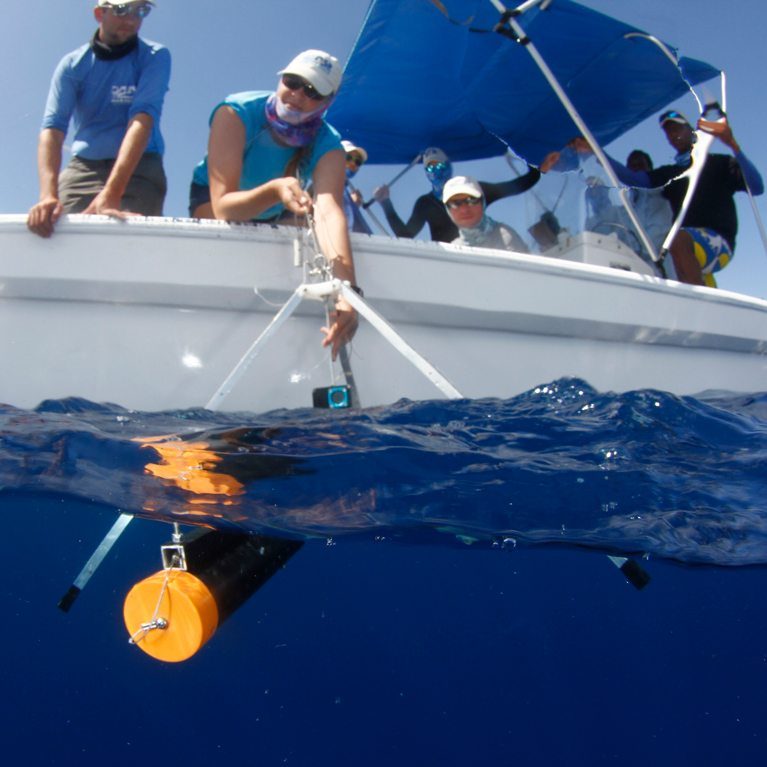

Lighthouse Reef, Glover’s Reef and Turneffe Atoll in Belize, Central America, make up three of the four off-shore atolls in the Caribbean. Known as the Mesoamerican Barrier Reef System, these atolls are part of the second largest barrier reef system in the world. Many fishers – though based in coastal communities – fish far from their homes and use the atolls of Belize’s barrier reef as base camps. As such, all three of Belize’s atolls are important fishing areas for communities throughout the country. The atolls’ proximity to deep water (more than 1,500 metres deep, one kilometre from shore) puts unmonitored deep-sea fish species easily within range of these fishers. Tour operators based in more coastal locations have also recently begun taking guests to participate in ‘deep drop’ fishing, and shark by-catch has been documented in these operations. Historically, deep-sea fisheries have often already been well established and fish populations in decline before any biological surveys are conducted. This is especially true for shark species, which suffer from a general lack of data worldwide and typically exhibit life history strategies that make them vulnerable to overexploitation. These characteristics make deep-water shark species slow to recover from exploitation, while their deep habitats also make them difficult to study. The Belize government’s interest in expanding shark fisheries, along with the threat from poaching and illegal export, puts these species at risk before they have even been identified and characterised.

Working with local fishers during our normal fishery-independent field work in Belize, we learned of the deep-water fishing practices some of them were adopting. Deep-water fisheries are well-established in many developing countries, and destructive fishing practices have been mostly allowed to go on unchecked in many of these regions. The scale of the deep-water fishery in Belize appears to be small for the time being, but rapid expansion could occur with the influx of larger fishing vessels from other countries. Traditional fishers have reported catches of a number of deep-water shark species, including sixgill and sevengill sharks, dogfishes and even a possible goblin shark. Local tour operators bringing guests out for deep-drop fishing have also reported capturing sixgill and sevengill sharks just metres from the barrier reef. These catches and encounters are generally chalked up to anecdotes, with the fishers rarely reporting or photographing their bizarre catches. Likewise, it is generally only when specifically asked that fishers will tell of the small shark with large green eyes that they caught several months ago. However, as these stories added up, it became apparent that not only were fishers catching deep-water sharks, but they were increasingly targeting deep-water fishes as part of their normal fishing practices. Many fishers are bringing sharks up along with their snappers from depths over 400 metres.

The aims and objectives of this project are to:

- Characterise the scope of deep-water fisheries in Belize.

- Identify and survey deep-water fishers to determine levels of effort, gears used, species caught and economic importance.

- Collect morphological information and tissue for species identification.

- Train fishers to measure, tag and release live deep-water shark species and collect samples from mortalities.

- Characterise deep-water shark assemblages in Belize through fisheries-independent sampling.

- Conduct fishery-independent surveys with fishers to target deep-water shark species.

- Provide science-based information for the precautionary management of deep-water fisheries.

- Raise awareness of deep-water shark species among Belize’s stakeholders through multiple channels, including social media, presentations, written publications and large public events.