There’s something about sawsharks…

Managing sawshark populations requires good information on where they move and what their relative abundance. Jane and Paddy are using a variety of methods to improve our understanding of the conservation status and management of sawsharks threatened by fishing in south-eastern Australia.

I grew up in a family connected to the ocean. Every holiday and numerous weekends were spent at the beach and many of my foundation memories of childhood feature family, surf and fishing. I distinctly remember deciding to become a marine biologist after watching David Attenborough’s 1979 BBC series Life on Earth as a child. I have been fortunate in life to have achieved my childhood passion and to have surrounded myself with an equally passionate, enriching and supportive group of family, friends and colleagues.

I completed a BSc at the University of Sydney in Australia, then an MSc at the...

Kentucky is probably one of the stranger places for a marine biologist to come from; the closest access to the ocean was about a nine-hour drive east. Nevertheless, I always felt drawn to the ocean, even though I grew up so far away. I was fortunate enough to spend summers at the beach along the east coast of the USA, summers that sparked my interest in the ocean at a very young age. There was always something to see just below the surface – fish, crabs, jellyfish, sharks – and all of it such a mystery to me as a...

Diversity, Dynamics and Destinations of Sawsharks from Southeastern Australia

Improve the conservation status and management of two species of sawsharks heavily impacted by commercial fishing in southeastern Australia. This will be achieved using analysis of movement and migratory patterns (tagging via satellite telemetry), trophic structure (fatty acid and stable isotope analyses), genetic structure (DNA markers) and multidimensional modelling.

Predicting the population structure of elasmobranchs is difficult, especially for deeper-water benthic species. In theory, large-bodied elasmobranchs in pelagic waters have higher vagility than their demersal counterparts and are expected to have low or no population structure (panmixia). Many pelagic and benthic species show patterns contrary to this expectation, however, such as whale sharks and cownose rays. Even sympatric species can show contrasting population structure. Because population structure cannot be reliably predicted, best management practice requires assessment at the individual species level.

Seven of the eight species of sawsharks globally are fished by trawling, gill netting or longlining yet little is known about the long-term impacts of this fishing pressure. Common and southern sawsharks have been commercially fished for over 90 years in Australian fisheries, but the ongoing sustainability of this harvest is unknown. We need to assess population structure and movement patterns now to truly understand their conservation status.

Sawsharks typically inhabit benthic habitats of the continental shelves and slopes, ranging in depth from 0-1240+ metres. As our knowledge of their depth is reliant on commercial catch data, it is likely that they inhabit waters deeper than this. Sawsharks are demersal and live on sand and gravel habitats with little complexity. Two Australian species have overlapping distributions in latitude and depth: the Common Sawshark (Pristiophorus cirratus) and the Southern Sawshark (P. nudipinnus). Initial studies of diet and stable isotopes of the species suggest resource partitioning occurs between the species where their distributions overlap.

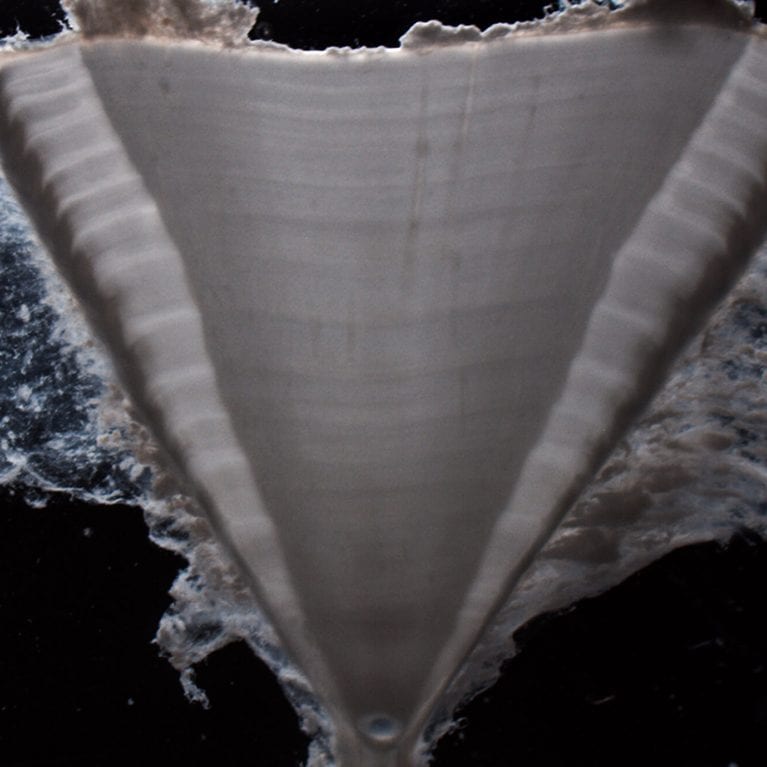

Two distinctive features of pristiophorids are their barbels and rostrum. The rostrum is an elongation of the skull’s rostral process and is armed with modified dermal denticles (rostral teeth). Unlike any other elasmobranch, Pristiophurus are characterised by whisker-like barbels. Precisely how sawsharks use their barbels and rostrum is unknown, however, it is presumed that these structures act in a tactile manner to sense and capture prey.

These sharks are relatively small, growing to a maximum length of ~150 cm, with females growing larger and weighing more than males. Accurate ageing is difficult, but estimated lifespan is nine to 15 years. Pristiophorids are ovoviviparious. Time of breeding is unknown but is thought to be during the austral winter.

The major threat to sawsharks is commercial fishing. P. cirratus and P. nudipinnus have been routinely caught as incidental bycatch by commercial fisheries for over 90 years. Circumstantial evidence suggests that the size and number of individuals have declined over the century. The IUCN lists these species under the category of “Least Concern” because catches are restricted by annually revised quotas. Sawsharks in other areas globally are listed as “Near Threatened”, “Data Deficient” or are yet to be formally assessed due to poor understanding of their biology, demography and ecology. Current assessments of their sustainability status are difficult. For example, it is unclear whether P. japonicus is a naturally rare species or if the species has already been depleted through commercial fishing.

Understanding past baselines is always difficult in species that have been exploited over long periods of time. Decreases in population size can result in a loss of genetic diversity and have a deleterious effect on population fitness. Understanding losses of past fitness will facilitate assessments of exploitation and give insight into future conservation efforts. P. cirratus and P. nudipinnus exhibit wide distributions across Southern Australia. Such extensive distributions often harbour cryptic species and spatially-structured genetic subdivision, and it is uncertain if eastern and western populations of each species are genetically distinct. Genetic diversity is directly related to extinction risk. In general, more genetically diverse populations can cope with higher levels of threats, such as fishing. Prolonged threats can lower genetic diversity and increase the susceptibility of impacts to populations. Our proposed research will use molecular analysis to unequivocally establish the population structure and resilience of the two species.

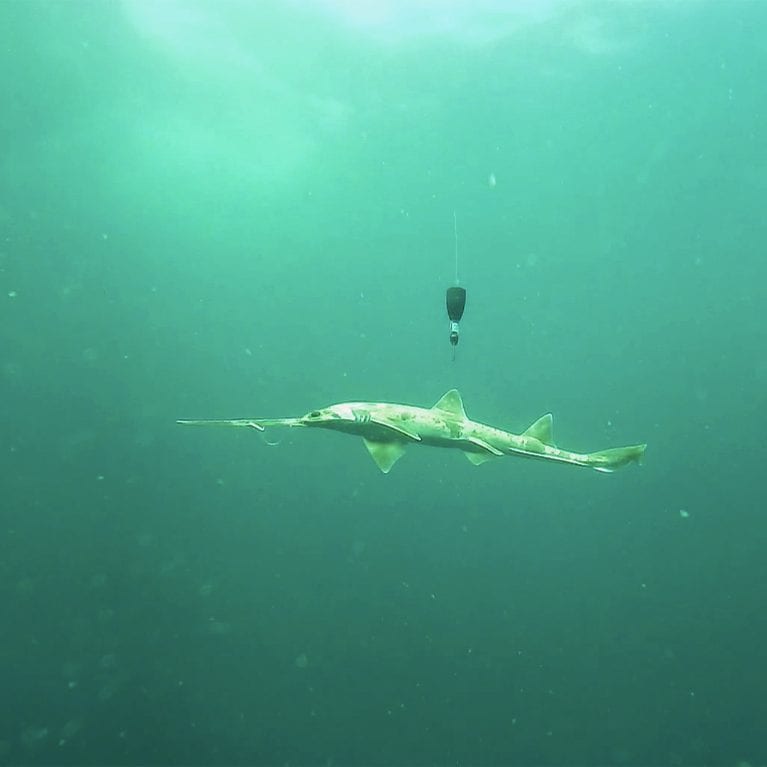

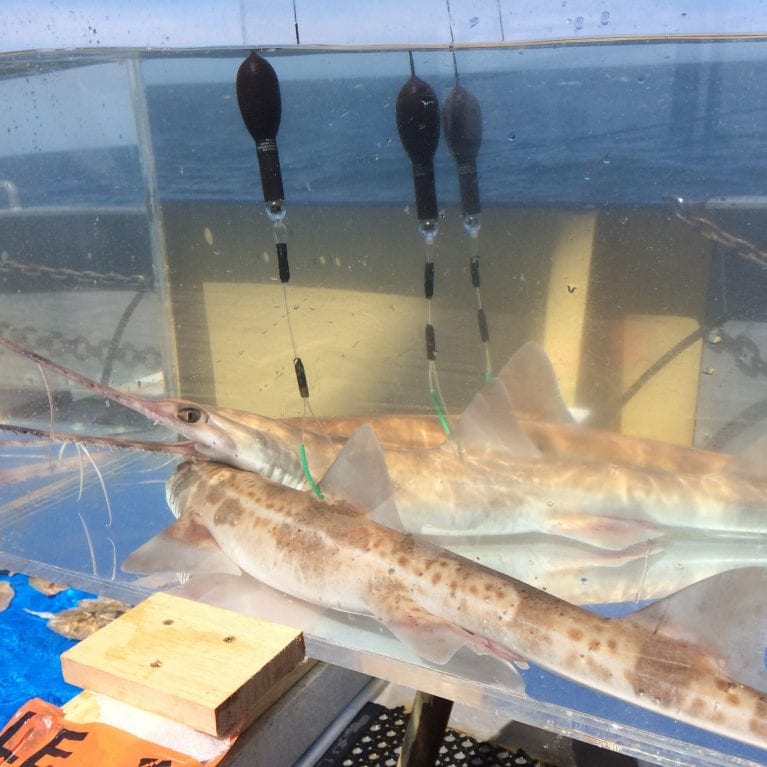

Little is known of movement patterns of deep water benthic sharks. Based on movements of their shallower counterparts, it is presumed that they display high site fidelity and residency. In my pilot study of P. cirratus tagged with PSATs, however, individuals moved over 250 km in 30 days exhibiting movement on scales larger than expected. Our proposed research will assess shark movement in relation to habitat use, diet and abiotic parameters through tagging, Fatty Acid Analysis, Stable Isotope Analysis and multidimensional modelling.

- To define migration patterns, philopatric behaviour and environmental drivers of the two species of sawsharks in southeastern Australian waters through Pop-up Satellite Archival Tags (PSATs). PSATs will allow for detailed movement of benthic individuals to be assessed against abiotic measures like temperature and salinity.

- To establish habitat use and ecology of the two species of sawsharks using fatty acid analysis (FAA). Fatty acid biotracers can identify temperature ranges, habitat and trophic sources of foraging and can describe the surrounds the animal moves through with the PSATs. This method complements the SI objectives.

- To establish the ecological role of the two species by assessing their geographic diet and food-web interactions through stable isotope analysis (SI) and gut contents. These analyses determine the relative importance of the sharks in their local food web, prey choice, and dietary choice. This method complements the FAA objectives.

- To determine the population structure of the two species of sawsharks in southeastern Australian waters and assess for any evidence of multiple paternity. The first objective will assist management in commercial fisheries and the second will improve our understanding of sawshark reproductive biology and assist conservation efforts.

- To model results from the previous objectives into a multidimensional-scape, coined “The Sawscape”. We will then input data on other sawshark species globally to examine its broad utility. Our findings will be shared with the IUCN, managers, conservationists, and with the wider community through media outlets, workshops, and other outreach.