Keeping watch on Palmyra’s sharks

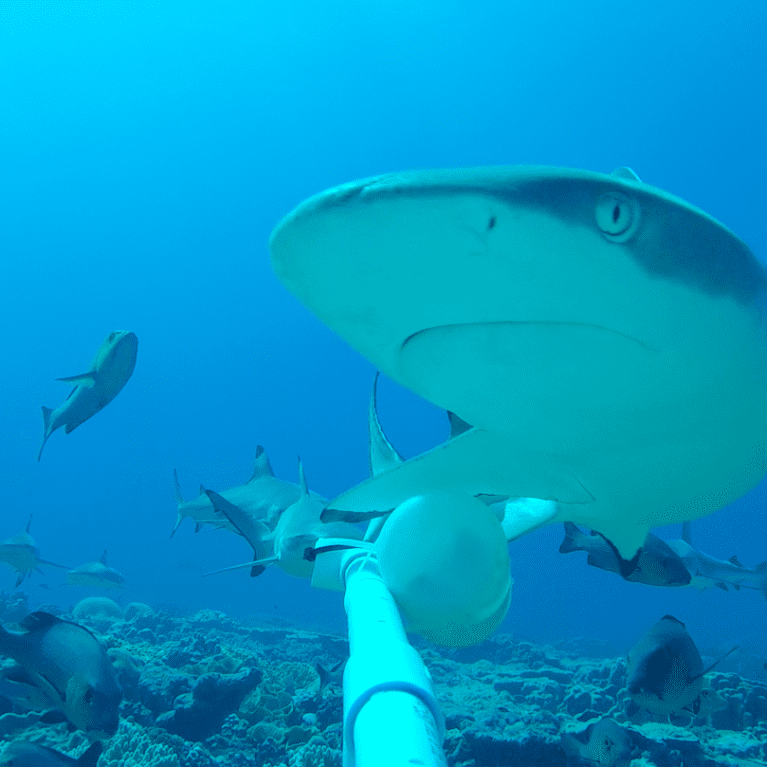

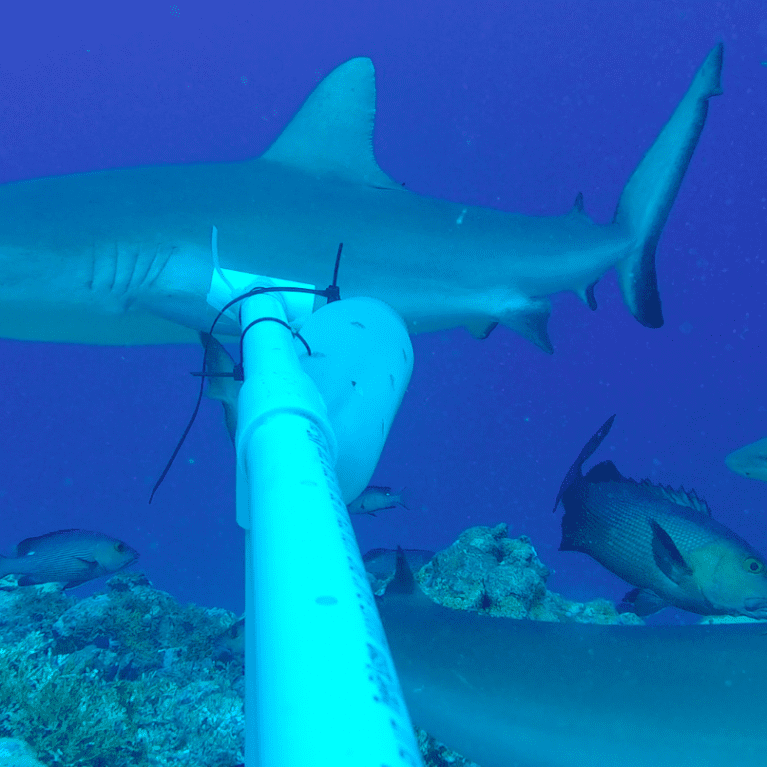

Divers are traditionally used to estimate shark numbers, but human presence changes shark behaviour and can make these estimates inaccurate – but how inaccurate? By using underwater cameras to count sharks, Darcy aims to answer this question.

The first shark I ever saw was a leopard shark, swimming slowly beneath the shallow Californian waves. I was a small child surfing on a body board and my instinct drove me to ditch the board and dive in towards the shark to take a closer look. A strong survival instinct has never been my strong suit, but my fascination for sharks has continued and never wavered. Whether snorkelling or diving, I am always the person looking out towards the open ocean, waiting, hoping, willing something big to swim by.

My shark fascination became a commitment to shark conservation when,...

Accounting for shark behaviour in estimates of reef shark population size and abundance

This project aims to establish the behavioural response of reef sharks to human presence (during diving, snorkelling, boating and provisioning) and then to quantify that response as a correction factor in order to correct bias in existing estimates resulting from diver-based visual surveys.

The way in which individual sharks interact with humans makes it nearly impossible to assess accurately shark populations with diver-based visual surveys. For example, in areas with little human presence, sharks may approach SCUBA divers out of curiosity, positively biasing abundance estimates. Conversely, in regions with consistent diving activity, sharks may acclimatise to diving and display no reaction or even possible evasion to diving activity, negatively biasing population estimates.

This is disconcerting as shark populations associated with both the pelagic environment and coral reefs are estimated to have declined by as much as 90% globally. It’s critically important that we work to improve the accuracy of estimates of shark population size and abundance by accounting for behavioural biases. By doing so, we can better assess a species’ conservation status and prioritise and inform marine management.

Animal behaviour is known to bias significantly estimates of population size and abundance. Avoidance behaviour may lead to underestimates of population size, whereas curiosity may positively bias abundance estimates. Reef sharks are known to display a wide range of behavioural responses to SCUBA divers and snorkelers, provisioning activities and boating. However, rarely are these behaviours considered in estimates of population size. Given that previously non-targeted coral reef-associated sharks are now declining at rates similar to their pelagic counterparts, it is imperative that we accurately assess reef shark abundance and changes in population size through time.

Palmyra Atoll in the northern Line Islands provides a unique opportunity to assess how a natural coral reef ecosystem functions in the absence of extractive fishing pressure. Palmyra is a remote, uninhabited US National Wildlife Refuge in the central Pacific Ocean that supports a large population of grey reef Carcharhinus amblyrhynchos and blacktip reef sharks Carcharhinus melanopterus. Given the absence of fishing, shark populations are thought to exist at a stable carrying capacity. However, different visual survey methods conducted by NOAA’s Coral Reef Ecosystem Division (CRED) between 2001 and 2008 reveal fluctuations in shark counts. For example, grey reef shark numbers appear to be declining according to counts made using underwater transects. Yet during the same time period, grey reef shark counts increased for surveys conducted by towed divers. This begs the question: does human presence have a quantifiable effect on the behaviour of reef sharks at Palmyra Atoll? And if yes, what are the consequences of this bias on visual survey estimates of reef shark abundance?

- Quantify the behavioural response of reef sharks to diving and snorkelling.

- Quantify the behavioural response of reef sharks to boating.

- Quantify the behavioural response of reef sharks to provisioning (during non-extractive fishing activities).

- Correct and calibrate existing visual survey estimates based on the above findings.