A decade at the D’Arros Research Centre

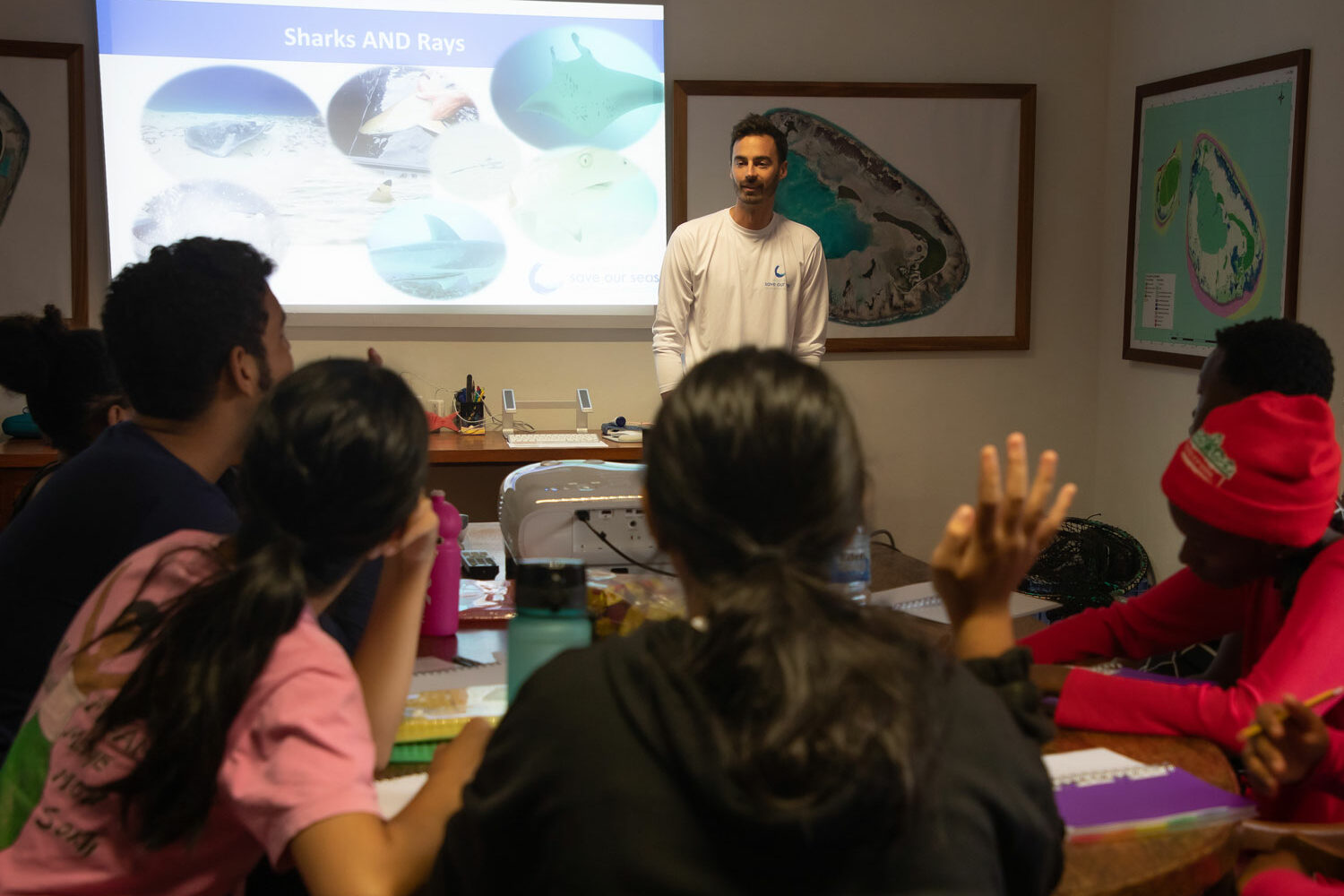

‘There is so much still to do. There is so much we can do to teach people about threatened species and what we’re doing to protect them,’ begins Ellie Moulinie, a research officer at the Save Our Seas Foundation D’Arros Research Centre (SOSF-DRC). ‘I’d add to that,’ offers Dr Robert Bullock, the research director on D’Arros Island. ‘There’s only so much you can tell people, children in particular, about conservation and the environment without the story becoming sad or boring. But if you can just show them…’

The SOSF-DRC team of four, comprising research officers Dillys Pouponeau and Ellie together with Robert and programme director Henriette Grimmel, are well aware of the importance of the island ecosystem where they work. And as they reflect this month on a decade of research at the SOSF-DRC and celebrate the Save Our Seas Foundation’s management presence on D’Arros, their focus remains on what broader value their work contributes to conservation in Seychelles. ‘It’s extremely valuable that people can access this near-pristine environment,’ explains Dillys. ‘And they can do so through direct experiences such as our environmental camps for children or through the information we can share from the findings of our research and monitoring projects.’

Photo © Christopher Vaughan-Jones

A wild place of wonder

D’Arros Island hovers like a green thumbprint in the vast blue of the Western Indian Ocean. It is only one of 115 islands that are flecked across the Republic of Seychelles’ vast territorial waters – its exclusive economic zone – but it lies roughly 255 kilometres (160 miles) south-west of the archipelago’s largest island, Mahé, making it one of the remote and largely uninhabited Outer Islands of the Amirantes group. Accessibility becomes a key word when discussing D’Arros and its neighbour St Joseph Atoll (they are managed together as a single ecological unit). Indeed, the fact that they are so inaccessible – D’Arros lies 45 kilometres (28 miles) from the commercial flight path heading to Desroches Island – may have kept this region relatively wild and ecologically functional.

But without some idea of the value of the role these islands play in maintaining the environmental health of Seychelles and contributing to livelihoods in the Western Indian Ocean, it is harder to understand how to manage it and justify its continued protection. That’s where a decade of insights from the SOSF-DRC comes in to form the basis of the region’s future.

A rapid biodiversity survey in 2017 by the SOSF-DRC recorded 514 marine species from 17 different families here. The team puts it another way in its most recent scientific publication: the species recorded here make up almost two-thirds of all reef-associated species ever documented in Seychelles. Of the species noted in the survey, 22 were new records for Seychelles (16 of these were fish) and one was entirely new to science. The discovery of the tiny goby fish Eviota dalyi, or Daly’s dwarf goby, was a hint as to the rich and complex life that still needs to be discovered and understood in this region. The findings also indicate why the region is an ideal site for a research centre and how protection here can contribute significantly to the overall conservation of marine life across Seychelles.

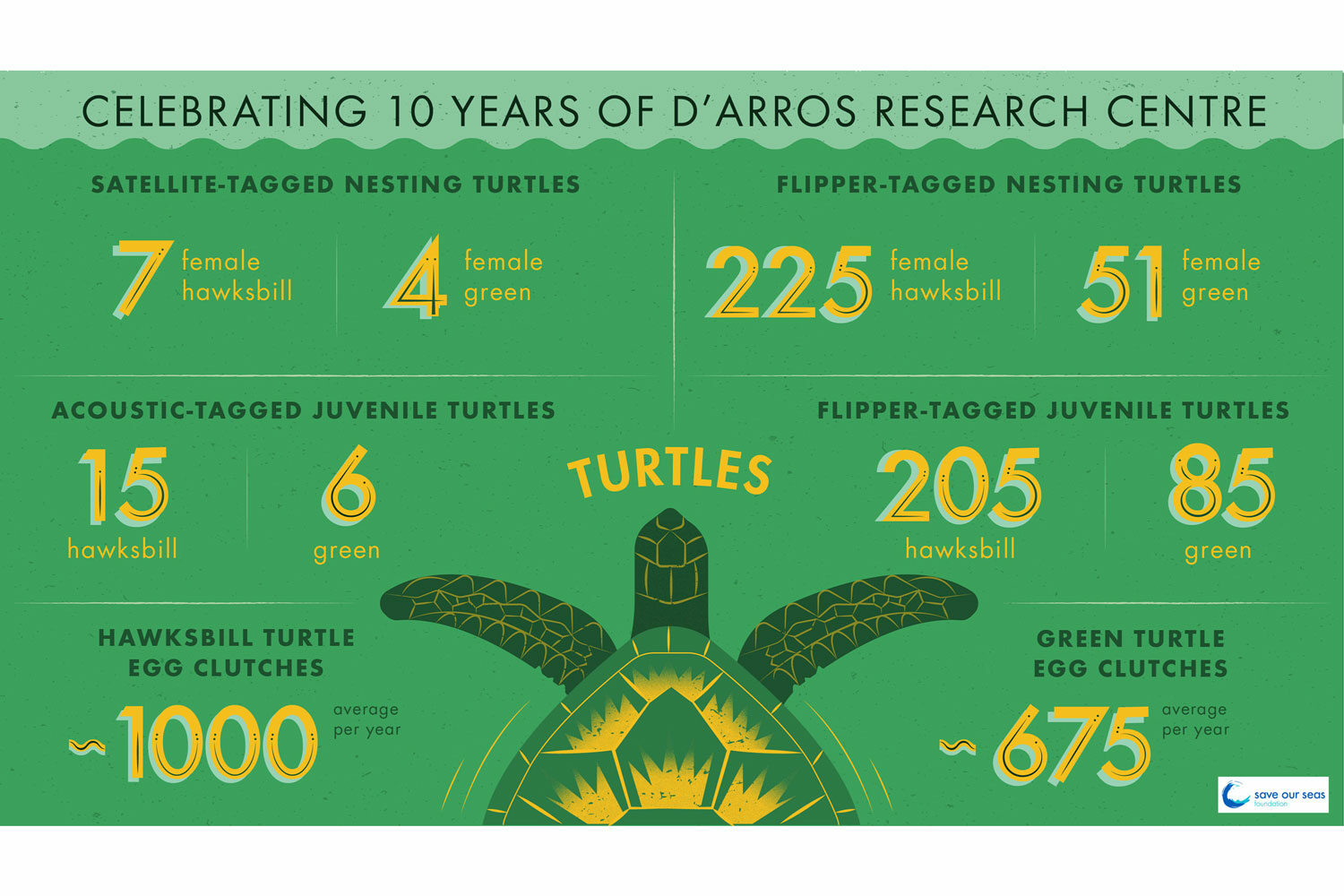

Going further back in time, Dr Jeanne Mortimer has been monitoring turtles in the region for so long, she has earned the nickname ‘Madame Torti’. She has demonstrated that Critically Endangered hawksbill and Endangered green turtles use the area for nesting. Her monitoring has also shown that about 1,000 hawksbill and 675 green turtle egg clutches are brooded annually, an astounding phenomenon that may set new generations of tiny turtles off to replenish ailing population numbers elsewhere. And when Dr Kevin Weng and Andrew Grey tagged 20 humphead wrasse, they showed how important D’Arros Island and St Joseph Atoll are to this ponderous-looking reef fish too. The humphead wrasse is Endangered but also hugely important to commercial fisheries and tourism, and it seems that a population uses specific parts of this remote haven as refuge.

click on images to enlarge & find out more

Of the 19 different species that researchers have studied directly at the SOSF-DRC in the past decade, 15 are considered threatened according to the International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red List of Threatened Species. Endangered sharks and turtles, vulnerable stingrays, manta rays and Aldabra tortoises and the largest nesting population of wedge-tailed shearwaters in the Western Indian Ocean make this a site not only of surreal biodiversity richness, but also of critical conservation importance.

For these reasons, D’Arros Island and St Joseph Atoll are recognised as a Key Biodiversity Area (KBA). This is an area where, if suitable protection and management are prioritised, we can significantly repair the environment and ensure that its functions healthily. With skies aflutter with lesser noddies and fairy terns, frigatebirds, tropicbirds and crested terns, the region has also been identified as an Important Bird Area (IBA). In addition, in 2020 D’Arros Island and St Joseph Atoll were each gazetted by the Seychelles’ government as marine protected areas. With the largest aggregation of reef manta rays in all Seychelles socialising at coral cleaning sites around the islands and healthy fish populations that are important for replenishing exploited sites elsewhere on the Amirantes Bank, it’s little wonder that D’Arros and St Joseph are considered critical for marine biodiversity.

A decade of research action

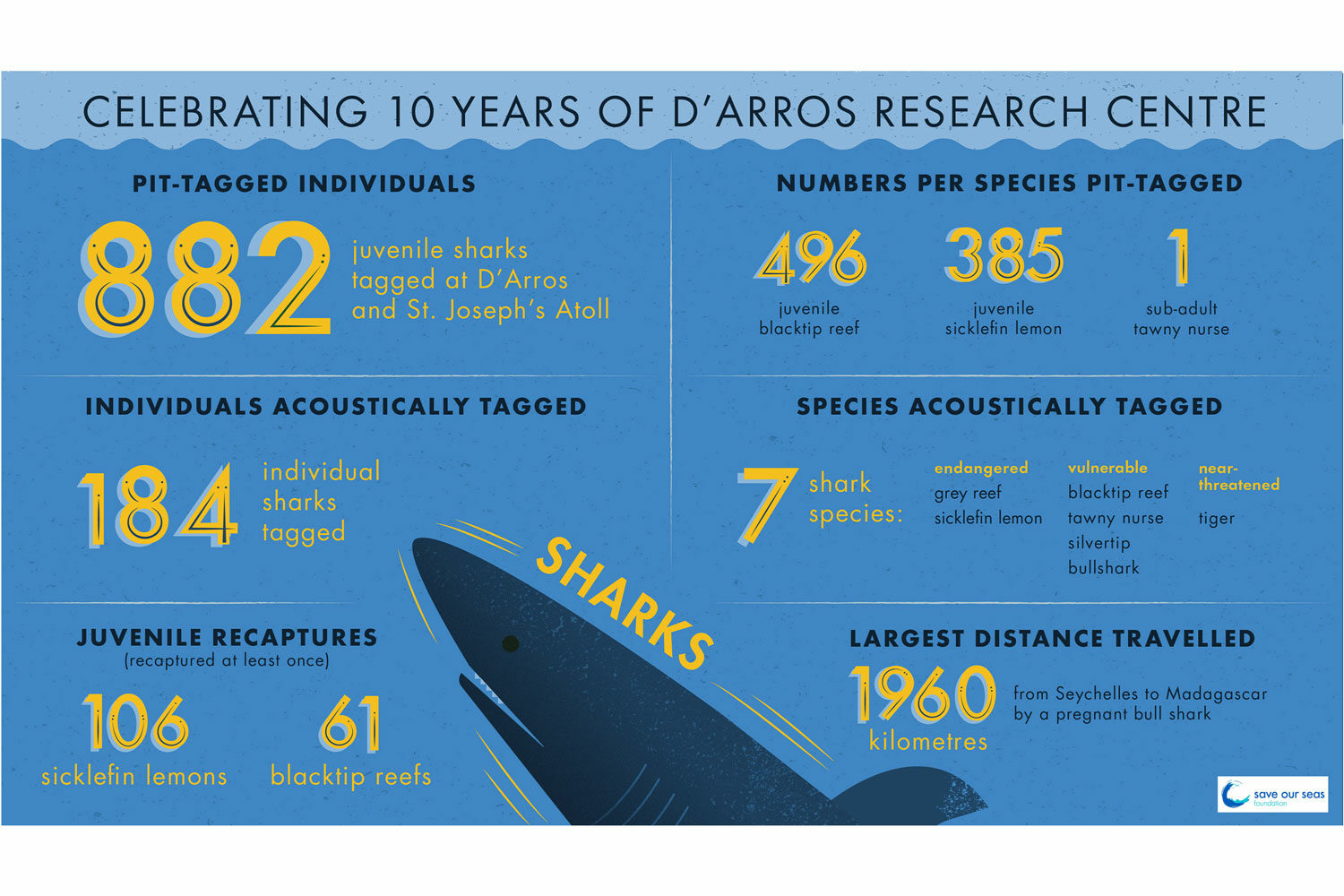

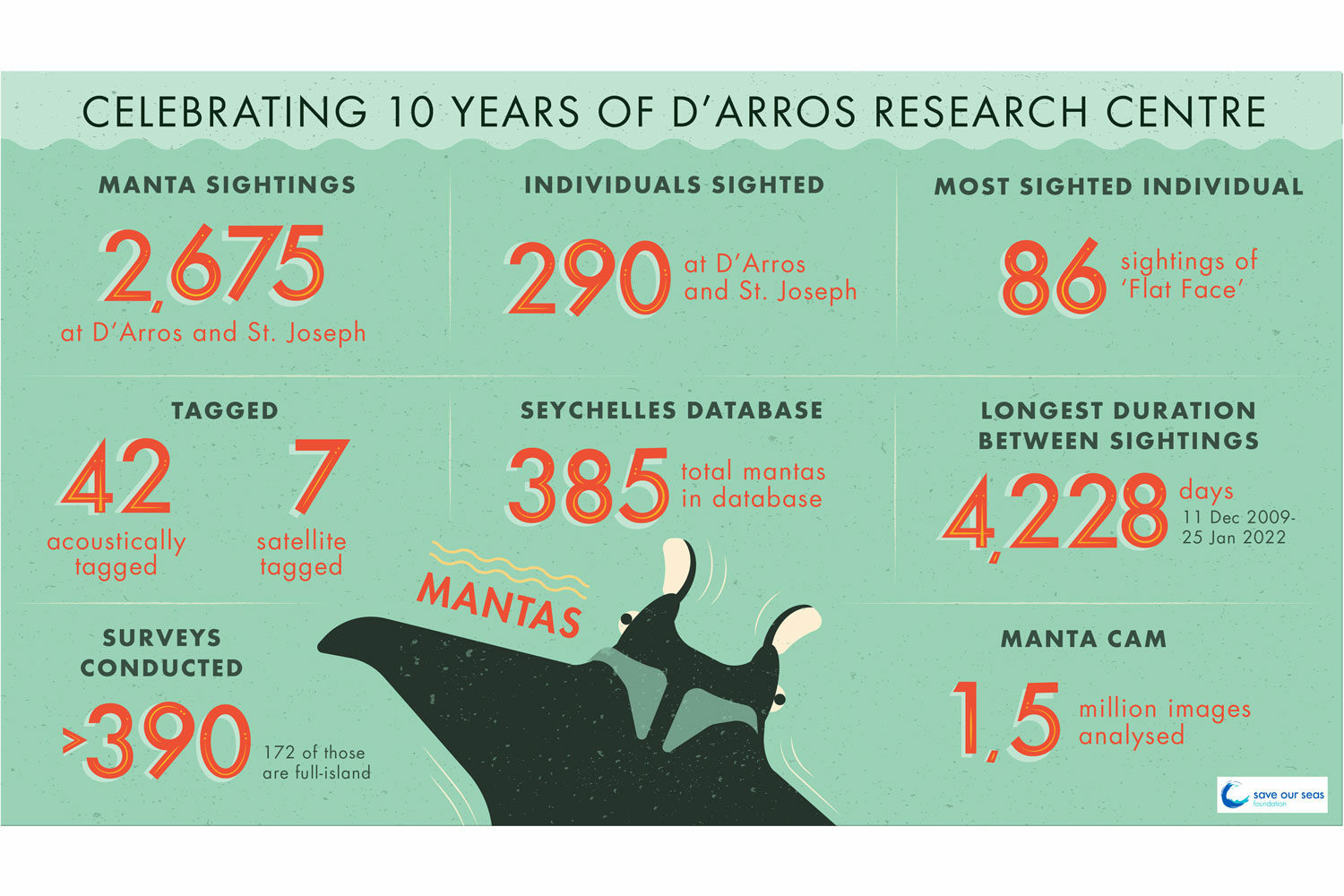

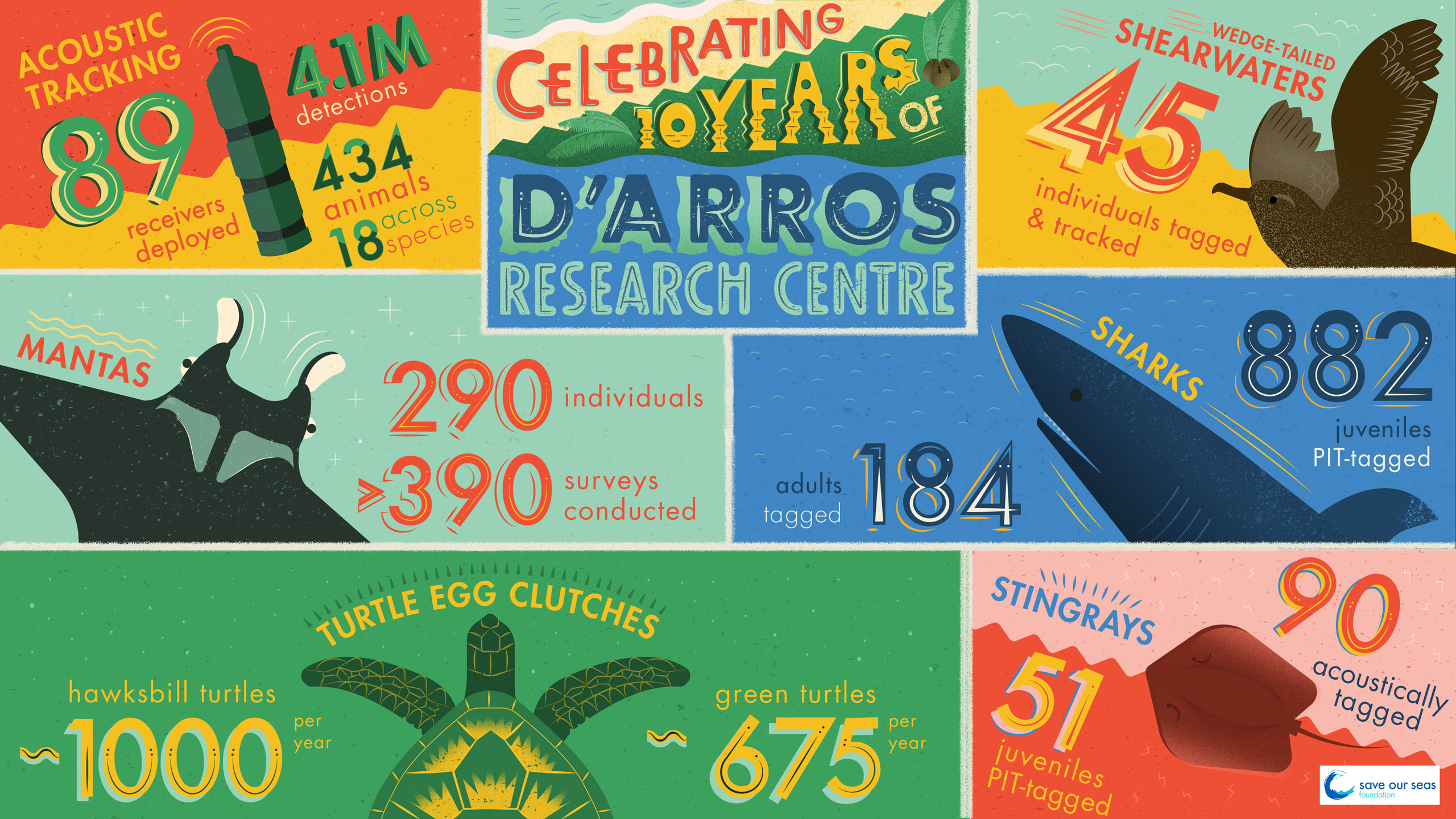

Celebrating 10 years of research at the D'Arros Research Centre. Artwork by Jamy Silver | © Save Our Seas Foundation

‘We sit currently with an incredible basis of understanding. Moving forward, our job is to join the dots between research and conservation.’ Dr Robert Bullock took the research directorship reins in 2020 and speaks to a contemporary vision: ‘At this point in time, research must be intrinsically linked to conservation. The questions that we ask must be linked to finding answers to species conservation issues.’

The foundation of knowledge that the current SOSF-DRC has in place comes from a long line of project successes. At a time when sharks are one of the most threatened taxa on earth, the SOSF-DRC comes into its own when devising and executing elasmobranch projects. ‘The majority of threatened species that use these islands are elasmobranchs [sharks, rays and skates]. When you look at such species, you look at what they need: nurseries, foraging grounds, life-long homes,’ explains Robert.

To understand where and how these animals are moving around D’Arros and St Joseph, and the broader Amirantes, researchers have tagged 184 sharks of seven different species, two of which are Endangered. A network of 89 acoustic receivers in the region ‘listen’ for the unique ‘ping’ of a tagged animal’s signal as it swims past. From the 4.1 million detections gained from the 434 sharks, rays, turtles and fish that have been tagged here, we have learnt of remarkable feats, like that of the pregnant bull shark that swam 1,960 kilometres (1,218 miles) from Seychelles to Madagascar. More than 390 surveys have been conducted on reef manta rays, during the course of which 290 individuals have been sighted. Of these, the most frequently encountered was a manta called Flat-Face, seen 86 times! Ninety adult and 51 juvenile stingrays of three species – mangrove whiptail, porcupine ray and cowtail ray – have been tagged and tracked. In addition, the habits of hawksbill and green turtles are known from 276 flipper-tagged and 11 satellite-tagged nesting individuals, while 45 wedge-tailed shearwaters have also been tagged and tracked.

Improving our understanding for conservation management

The numbers are interesting and impressive, but what do they really mean for our understanding? ‘The answers need to translate into practical outputs. How do we define the marine protected area and how is it best managed? What do we need to do to protect threatened species adequately? These kinds of questions can only be answered by timely and prudent research,’ says Robert. So, for example, we know from Dr Lauren Peel’s work that reef manta rays play a unique role in bringing critical nutrients to the coral reefs that thrive around the islands. We have also learnt that these rays are highly resident in Seychelles, using D’Arros Island and St Joseph Atoll as a key site. Protecting reef manta rays where they spend most of their time will therefore also keep the coral reef ecosystem healthy because the ‘ecosystem service’ of nutrient cycling is preserved.

Research conducted by Elena Gadoutsis has revealed that the tapestry of life recorded around D’Arros, being as intact as it is, may have helped corals here recover more quickly from recent bleaching episodes that decimated other corals across the globe. As the planet’s climate changes, warming seas and rising pH levels herald more frequent and severe bleaching episodes in future. Protecting a place where corals are more resilient to this onslaught would be a climate-wise policy decision.

Thanks to the work of Dr Ornella Weideli we have a better understanding of the value of St Joseph Atoll as an important nursery for shark pups, and Endangered sicklefin lemon and Vulnerable blacktip reef sharks in particular. Dr Weideli has shown that the majority of these sharks were caught in a mark-recapture study not even 500 metres (547 yards) from where they were first tagged! The IUCN’s Important Shark and Ray Areas (ISRAs) process, launched this year, focuses on identifying sites like D’Arros and St Joseph that are critical to sharks during vulnerable life stages. Protecting sharks where they can grow to breeding age is important if we are to repair their plummeting population numbers. And as Dr Weideli also revealed, the condition of shark pups raised in the protected waters of St Joseph Atoll is better than that of pups growing up in more degraded coastal systems. A functioning, pristine nursery where food is abundant and threats are minimised gives shark pups a much-needed boost in life.

And getting insights into the secret lives of stingrays – the 90 individual mangrove whiptail, cowtail and porcupine rays Dr Chantel Elston tagged and tracked around St Joseph Atoll’s lagoon – was part of learning how animals in the middle of the food chain use the islands and what role they play in the ecosystem

A student from the D'Arros Experience Kid's Camp explores the wonders of the coral reefs surrounding D'Arros. Photo Dillys Pouponeau | © Save Our Seas Foundation

A haven of hope in the Western Indian Ocean

The past decade has seen more than 30 scientific publications stream out of the SOSF-DRC’s long-term monitoring activities and projects undertaken by visiting researchers and students. There have been startling scientific discoveries and heartening conservation insights. Certainly, 10 years have served to cement some of our understanding of the value of D’Arros Island and St Joseph Atoll for the rich natural heritage of Seychelles. However, the question remains: what is the broader application of this work to Seychelles, the Western Indian Ocean – and to us?

‘The SOSF-DRC has always been a research centre and ultimately it will always remain a research centre,’ reflects programme director Henriette Grimmel. ‘But I think now we are heading along a path to decipher how to make sure the research translates into action.’ She muses for a moment, then continues, ‘The world is complex. It’s not a given that the best available science is taken up into policy and enacted. But I think that here in Seychelles at least, much work is done to ensure that the information we gather is shared and that the public can more easily learn about what we find.’ This point goes back to what Ellie said at the beginning: people who are interested in nature don’t necessarily have access to it, but they do want to learn. Dillys’s concluding statement is one of hope. ‘That’s why I think the education part of conservation is so important,’ she says.

The remoteness of D’Arros Island and St Joseph Atoll may make their value and importance to us hard to fathom – an ‘out-of-sight-out-of-mind’ conundrum, a question of never experiencing what the world once was and what the oceans might be if we manage them responsibly. However, the research insights from the SOSF-DRC show that a protected, near-pristine ocean wilderness is not just a thing of luxury; in our changing world, it’s an absolute necessity.

Mike Roberts, who leads the South African Research Chairs Initiative in Ocean Science and Marine Food Security and was the recipient of the 2020 Newton Prize, reflects in a recent article for the Mail & Guardian in South Africa that the Western Indian Ocean is on a path towards a food security, livelihoods and marine ecosystems disaster. The region of greatest impact encompasses the east coast of Africa and several small island nations, including Seychelles. Roberts’s timeline predicts serious implications in the next 15 years, based on research that shows that the Western Indian Ocean is warming faster than other oceans. Places like D’Arros and St Joseph Atoll may be remote in our human notions of physical distance, but in our borderless oceans their influence extends beyond the bounds of the Outer Islands. In the light of impending crises for fish stocks, healthy reefs at D’Arros could be an important source from which to replenish the Amirantes Bank. Species declines across the Western Indian Ocean are rapid, so the value of a haven where 15 threatened species are able to breed, feed and grow can’t be overstated.

If, as Roberts points out, the past decade has seen the building of a solid foundation of scientific evidence and understanding, part of the SOSF-DRC’s celebrations this month will certainly include looking ahead to the next 10 years. Where there is a strong foundation for decisions, the work of the SOSF-DRC can be shared to enact change: touching the curious minds of children through environmental camps, and convincing the minds of Seychellois and African leadership tasked with steering the region towards sustainability.