Jubilee the manta ray named in celebration of the 500th manta ray identified in Seychelles

No man is an island, but islands, united, can change the fate of a species

It is often said that ‘no man is an island’; that we need each other, and when we act together, we are stronger for it. This is the very essence of conservation. And fittingly, this metaphor comes to life with one of the best examples from the combined efforts of those living on a small island chain in the Seychelles.

The Seychelles Manta Ray Programme (SMRP), comprised of a network of collaborators from across Seychelles that include the Save Our Sea Foundation D’Arros Research Centre (SOSF-DRC), The Manta Trust, Blue Safari Seychelles, Island Conservation Society, Fregate Island and the Alphonse Foundation, has just identified the 500th individual manta ray. A juvenile male reef manta ray, aptly named ‘Jubilee’, unknowingly brought about this major milestone in manta research.

Reef manta ray feeds over coral reef off D'Arros Island, Seychelles. Photo by Shane Gross | © Save Our Seas Foundation

Why does this matter?

The momentous nature of this milestone is founded on over a decade of work that represents collaboration, dedication and teamwork across an entire archipelago. Founded in 2013, the SMRP was born from an alliance between the SOSF-DRC and The Manta Trust, and is the first long-term study of manta ray biology and ecology in the country.

‘From the start, we knew we wanted a research programme that could address some of the key questions and knowledge gaps for the reef manta ray in Seychelles. We wanted to understand its population size, the habitats the rays were using and the threats they were facing,’ says Dr Guy Stevens, CEO of The Manta Trust. ‘And, more broadly, we wanted to understand how manta rays were connected across the whole Seychelles archipelago.’

The reef manta ray

The reef manta ray is one of Seychelles’ most charismatic inhabitants, famed for its size, intelligence and gentle nature. Globally, they are classified as Vulnerable due to threats like overfishing, bycatch, and habitat degradation, but until recently, little was known about these rays in Seychelles, given the remote nature of their aggregation sites in the Outer Islands.

That began to change when researchers found a way to recognise and follow individual mantas over time:

‘Mantas all have patterns of spots on their bellies that are like fingerprints. They don’t change over the course of a lifetime and they’re unique to each individual,’ explains Henriette Grimmel, Programme Director for the SOSF-DRC. Henriette spends much of her working week with the reef manta rays that congregate right on the centre’s doorstep. She and the SOSF-DRC team conduct weekly surveys, skilfully free-diving beneath the feeding mantas and taking care not to disturb the animals as they capture images of their bellies.

Researchers use the unique spot patterns on the bellies of the reef mantas, which are unique to each manta – like fingerprints - to tell individuals apart. Photo by Shane Gross | © Save Our Seas Foundation

You’ve heard of eyes in the sky, but what about seabed sleuths?

In recent years, the SOSF-DRC has also installed the remote camera system ‘MantaCam’, which takes photographs at cleaning stations around the island every 10 seconds to record every manta ray that visits. It’s then up to the team to sift through hard drives full of images, examining those personalised patterns of blotches, spots and stripes and comparing them to existing photos in the database to see if there’s a match. In doing so, they can pinpoint if it’s an individual they’ve seen already or one that is new to the SMRP.

With such an extensive database of imagery, the team can also monitor important life events – like injuries and pregnancies. ‘When they’re in the third and fourth trimesters, you can tell by their baby bumps. And that all goes on record,’ says Henriette. ‘So you can see the shifts across individuals and across life stages as well by simply taking photos.’ Analysis also shows that 37% of the known population has some type of injury, mainly from shark bites, but some caused by fishing gear and boat propellers.

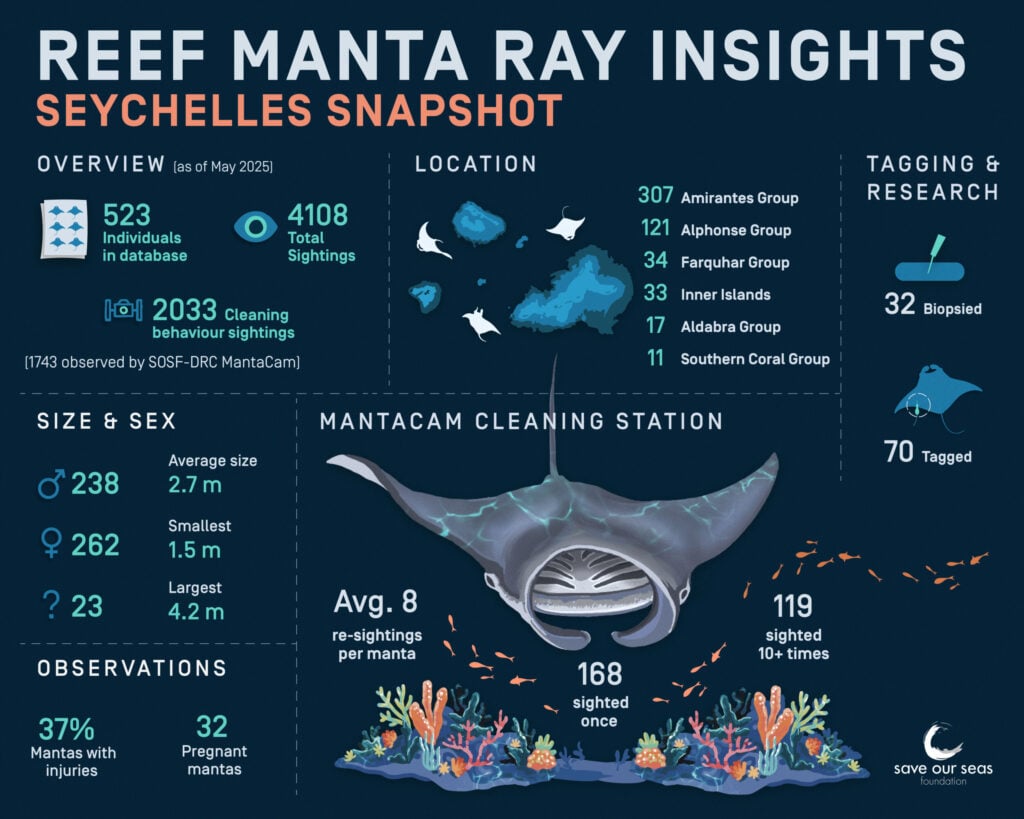

Infographic by Kelsey Dickson | © Save Our Seas Foundation

Turning insight into action

Collectively, this information is providing crucial insight into the behaviour, life histories and movements of reef manta rays in Seychelles – insight that can then be used to help protect them from threats, including bycatch and targeted fishing practices. Dr Lauren Peel has spent the past 10 years studying this population and has been integral to the development of the SMRP, initially as a project leader and now as project adviser. For Lauren, one of the most significant findings has been confirming the connectivity of reef manta rays between Seychelles’ Amirantes and the Alphonse Group. ‘Our confirmation of connectivity is significant because while individual mantas demonstrate high residency at the shallow aggregation sites in these areas, we now also know that they are also making the 200-kilometre (125-mile) journey between them, through waters reaching more than 1,000 metres (3,280 feet) deep,’ she explains. ‘This finding highlights the importance of protecting manta rays at known aggregation sites and shows how a protective network could benefit conservation efforts, not only within Seychelles, but across the broader Western Indian Ocean region too.’

These findings can be used not only to inform future conservation strategies and policies, but also to engage the wider public in reef manta ray conservation. By naming and tracking individual manta rays ‘we can engage people in the lives of these animals … creating empathy and connection in a very specific individual way’, says Guy. ‘And then you can talk about the things that have happened to that individual over time. Did it get bitten by a shark? Was it pregnant? Those are really connecting stories that make an impact.’

SOSF Research Director Dr. Robert Bullock photographs the underside of a manta ray for individual identification off D'Arros Island, Seychelles.

Perhaps one of the greatest stories is the manta ray that started it all. ‘Flat-Face’ was the first reef manta ray to be identified and catalogued – and, more than 10 years later, he’s still around. ‘He was here yesterday!’ smiles Henriette. ‘And he’s the most sighted individual in the country. He’s still going strong – and he’s not even mature yet.’

The regular efforts of the SOSF-DRC, combined with the data contributed by the SMRP’s collaborative partners and citizen scientists, have almost doubled the number of manta IDs in the past four years, enabling the programme to reach the celebratory 500th manta ray milestone. ‘To be honest, it renders me speechless and is a huge testament to all the hard work and community effort that the SMRP represents,’ says Lauren. ‘It’s very exciting to reach 500 individuals, with numbers still climbing, and there are large parts of the Seychelles archipelago still to explore for new aggregation sites.’

This milestone is a celebration of what can be achieved when communities, and organisations work together. This achievement reflects over a decade of collaboration, dedication, and meticulous care, with every new manta ray identified telling a story of their journeys, and their survival in the face of growing threats. Jubilee is a symbol of human commitment to understanding, and protecting one of the Seychelles’ most charismatic inhabitants. In this union of science, conservation, and community, we see the power of many hands working together to safeguard the future of these magnificent creatures. After all, no man is an island.

You can keep up with Seychelles’ reef manta rays, or submit your own sighting record here.

Alternatively, you can email smrp@mantatrust.org with the details of your sighting.

If you find a new manta, you will have the opportunity to name it!