Fear and fascination: has Jaws shaped how we talk about sharks?

It’s been 50 years since fear gripped the fictional beaches of Amity Island and fixated in swimmers’ minds at public beaches and in concrete swimming pools. We ask what the enduring legacy of this story has been for sharks, in a sea of stories told through time.

They swim into eternity on the rocks at Papa Vaka, ancient etchings around the island of Rapa Nui (Easter Island). They are reincarnated relatives turned guardian spirits of Hawaiian families. Their images have been unearthed from ancient Iranian ruins dating back 6,000 years, and their brass forms were shaped into counterweights used by Ghana’s Akan people to measure gold dust from 1400 AD until the advent of paper notes and coins.

We’ve been talking about sharks, rays and their relatives for tens of thousands of years. For many riverine and coastal communities, sharks and their stories were woven into a spiritual tapestry that formed the basis of custodianship; a kind of conservation founded on the understanding of kin and stewardship that disappeared with the tide of industrialised life in Western society. And the stories we’ve told have, over time, become lore mixed with both fear and reverence. There are benevolent sawfish spirits that ward off childhood illness in Nigeria, and there is the ‘hateful’ mako shark that the fisherman Santiago vows to fight ‘until I die’ in Hemingway’s Old Man and the Sea.

We’ve exaggerated their size, their capacity and their tempers; and we’ve underestimated their ecological roles and diversity. They have descended from gods to demons. American artist John Singelton Copley (who had never personally seen a shark) immortalised an unconvincing version – complete with nostrils and lips – in Watson and the Shark (1778), a painting depicting the real rescue of 14-year-old cabin boy Brook Watson. Even Jacques Cousteau wasn’t immune to fear-mongering, decrying them as divers’ ‘mortal enemies’. In a scene from The Silent World (1956), the oceanographer and his crew gaff and haul aboard scores of blue sharks and oceanic whitetips before bludgeoning them to death.

But there’s one story that is infamous for amplifying any fear, loathing or misunderstanding of sharks that was latent in our psyche far beyond what local lore or literature had done previously.

The Jaws effect

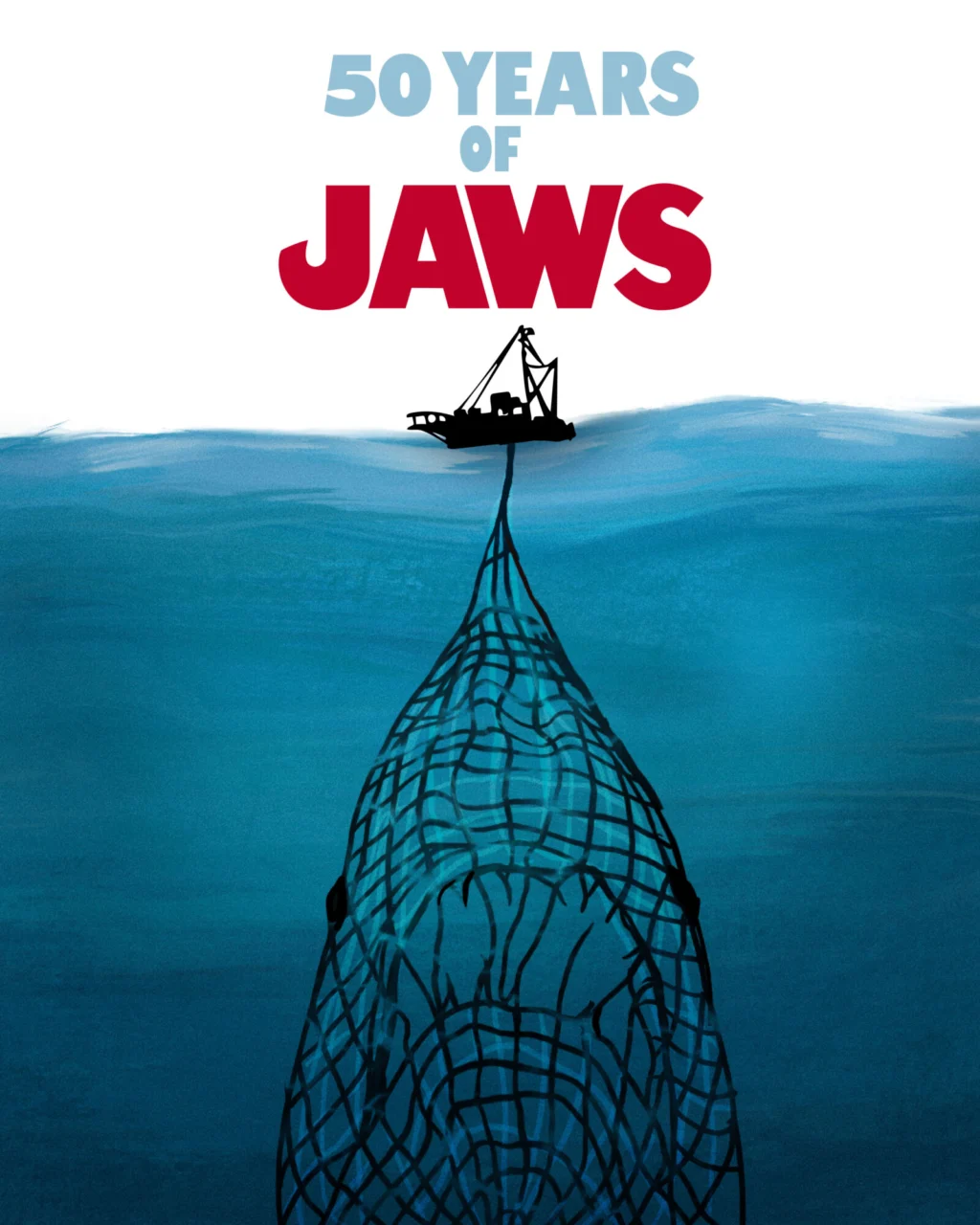

It’s been 50 years since Steven Spielberg’s mechanical shark launched itself into Western popular culture. Or rather, it is the anniversary of the two-note refrain played by a high-pitched tuba that haunted the nightmares of anyone submerged in the sea (or a landlocked pool, for that matter). Jaws, the novel by Peter Benchley, was published in 1974 and elevated to the silver screen the following year.

The collective panic that followed is now the stuff of legends (and shark conservation nightmares); reports abound of empty beaches in the summer of 1975, increased reporting of shark sightings and, more horrifyingly, a rise in the targeted killing of sharks. Many conservationists have argued over the following decades that the PR of sharks (already in the tricky realm of other animals like hyenas and vultures) had been devastated and that the film had made it harder to convince the public of the value of their conservation.

Ironically, the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES) came into force mere days after Jaws was released, but it would take a further 40 years before the white shark was listed on CITES Appendix II. A negative public perception and the avoidance of beaches are perhaps one end of a spectrum of consequences, but as policy researcher Dr Christopher Neff from the University of Sydney has pointed out, the way we speak about sharks can influence policy. And in the case of Western Australia, he has argued that the Jaws effect has seriously influenced policy responses to shark bite incidents on the coast even years after the film’s release.

Photo © Byron Dilkes

Unintended consequences

There has been much said about the damage Jaws has done. There’s been plenty of finger-pointing over the decades, and even the odd apology (both Jaws author Peter Benchley and filmmaker Spielberg have variously asserted the fictional nature of the movie and decried the declines of shark populations). But among the film’s litany of unintended consequences, a cohort of shark scientists and conservationists inspired by the film is perhaps one of the strangest.

And when it comes to wins for shark conservation, Amani Webber Schultz is a very happy unintended consequence of the Jaws effect. A PhD candidate at the New Jersey Institute of Technology, Amani is also the co-founder and the chief financial officer of Minorities in Shark Sciences, an organisation determined to make shark science a welcoming space for gender minorities of colour. ‘I felt fascination and a sense of pure entertainment,’ she enthuses about her first viewing of the film. ‘I think I’d heard so much about the film (and so much time had passed since it came out) that by the time I watched it, I already knew what the movie was about – and that it was an exaggeration and incorrect display of how sharks behave.’ So Jaws wasn’t perhaps Amani’s first encounter with sharks and their stories and she was equipped with the knowledge to debunk any real fear. But the film is not an isolated case of poor PR in shark storytelling. ‘When I was a kid, TV shows that focused on sharks really emphasised their “frightening” side. They all used scary music and words that could play very well into the fear of sharks as a whole.’

‘I watched Jaws much younger than I should have,’ Dr James Lea starts with a chuckle. ‘And I loved it as a film, and still do. I was a child who already feared the water and Jaws certainly played into some of my worries. But the fascination for sharks it sparked in me overrode all of that. I clearly remember wanting to get books on sharks and to learn more about them. I thought that the animal that you barely get to see in this film was so intriguing, I had to know as much as I could.’

The result of this fascination? A career in shark research and, ultimately, a lifetime dedicated to shark conservation as the CEO of the Save Our Seas Foundation. ‘I remember the books my parents could get me were overwhelmingly stories of attacks and survivors, and all the media we could find – aside from one or two biology-focused encyclopaedia-style books – played morbidly into our dual fear and fascination with sharks. It was difficult to find much else,’ he explains.

Photo © Matthew During

What’s the biggest issue with sharks?

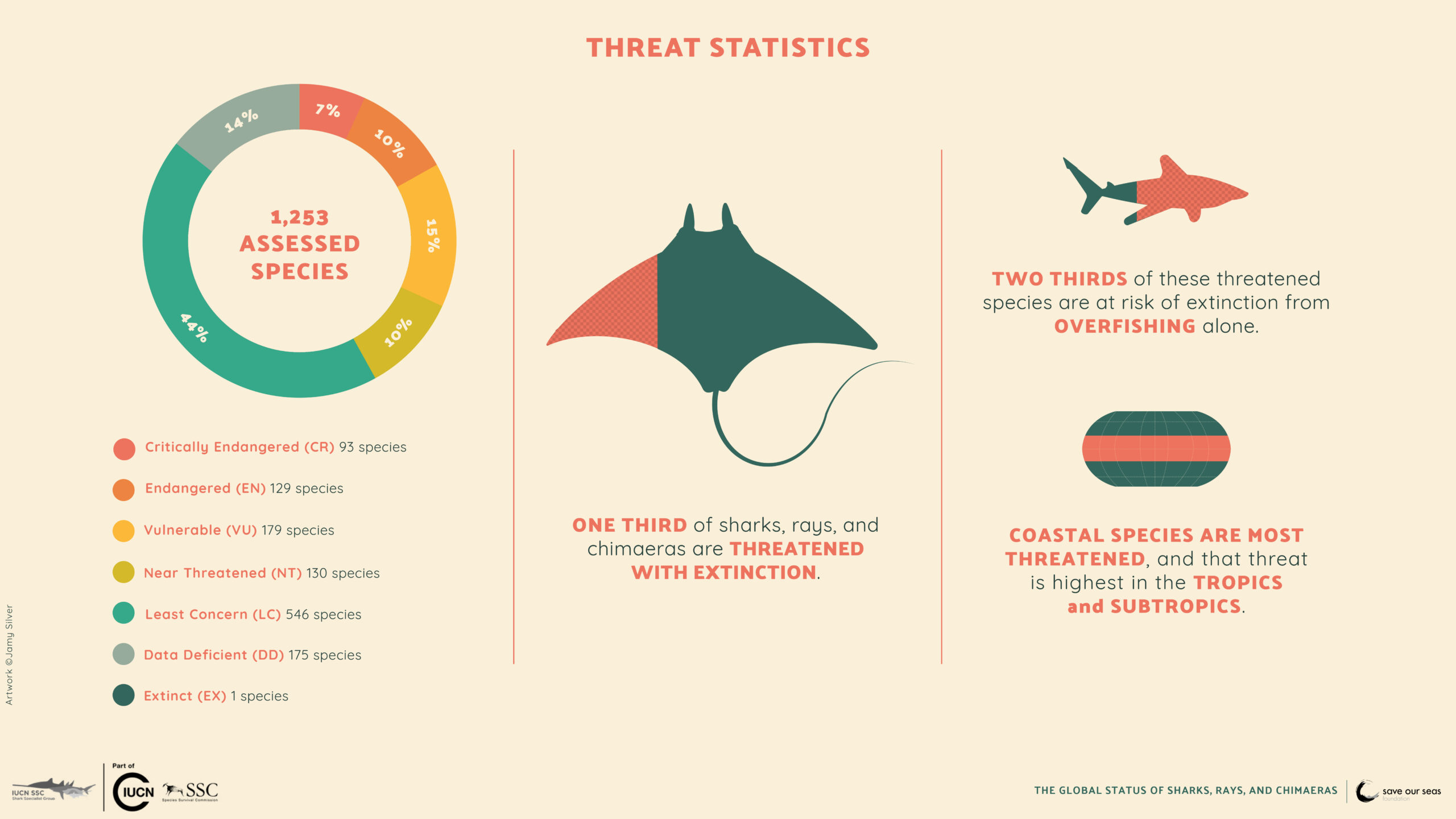

Overfishing is driving sharks to extinction. The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Shark Specialist Group (SSG) released its Global Report on Sharks, Rays, and Chimaeras last year. The consensus across its 2000 pages, compiled by 353 experts from 115 countries, is that Indonesia, Spain and India are the world’s largest shark-fishing nations, with Mexico and the USA adding to the top five shark catchers. But only 26% of species globally are targeted; most are caught (and retained) as bycatch. Huge declines have been seen in rhino rays (such as wedgefish), whiprays, angel sharks and gulper sharks.

These are not the charismatic large predators we typically associate with Jaws and the legacy of dubious shark cinema that has littered movie theatres in the years since. This is the consumption of sharks on a grand scale, to secure income, jobs and food. Thirty-seven per cent of sharks are disappearing due to industrial-scale fishing; 96% of all threatened sharks are taken by industrial fisheries in combination with others.

Infographic by Jamy Silver | © Save Our Seas Foundation

Certainly, recreational fishing and trophy and sport hunting remain issues. Echoes of Ernest Hemingway’s Old Man and the Sea are resurfacing in places around the world where shark populations are recovering as fishers target sharks as retribution for ‘depredation’ (eating fish from fishers’ lines). There has been no My Octopus Teacher equivalent – yet – where a single character salvages the PR image of sharks on the big screen; only perhaps bumbling Bruce and his ragtag band of needle-toothed comrades in the animated Finding Nemo limp sadly towards something more endearing.

But like all good horror films, Jaws only played on the seeds of something that was already planted in our minds and served to exaggerate them. ‘I think it works so well not because it makes you scared of sharks, but because we already have an ingrained sense of mystery and fear around these animals to begin with,’ muses James.

It is worth highlighting that the overriding story in shark conservation has, for decades, been dominated by our understanding of what this one film meant for our Western perception of sharks – and the impact it has had on the policies meted out in response to shark–human interactions. But what about the other stories of sharks? Those ones of gods and deities, of totems and guardian spirits? Why is it that sharks have fallen from grace, and what do we stand to lose as they disappear from places where their stories were tied to culture, ceremony and spirituality?

There are many places on the planet where information about sharks and rays is lacking: their conservation status, their diversity, their place in local ecosystems – indeed, their very existence. And yet, in some developing nations fishers have reported that more than 80% of their income depends on shark and ray fisheries. In a climate where Indigenous Ecological Knowledge – the voices of local communities and an ancient sense of stewardship – has in many cases been overridden by globalised consumption and conservation alike, perhaps there is value in reviewing how we include not only people and their ideas in our shark conservation future, but also their deep ties and stories.

Photo by Gabriella Angotti-Jones | © Save Our Seas Foundation

There is a world away from Amity Island

On 20 June 1975, Jaws was released on 464 screens across North America: 409 of these were in the USA, the remainder in Canada. Between 1975 and 1976, the film was released around the world. But in the decades since, that world has continued its orbit around the sun and people have remained tied to sharks in such a variety of different ways, it seems impossible that a single film’s impact could have been universal.

‘I grew up a little afraid of sharks,’ says Cyndi Ngnah, a Save Our Seas Foundation (SOSF) project leader who hails from Cameroon. ‘I was aware of them because they featured in some animations and movies, but always as a dangerous and aggressive animal. And I saw a lot of movies about sharks growing up, but not Jaws.’ Today, Cyndi herself works on shaping the stories we tell about sharks, creating and distributing culturally relevant cartoon animations to inspire young Cameroonians to act to save sharks and rays.

Her insights and experiences are not singular or isolated. Fellow Cameroonian project leader, and another researcher who started off at the African Marine Mammal Conservation Organisation (AMMCO), Wongibe Dieudonne grew up in a part of the country dominated by grasslands where bodies of water are rare. ‘My awareness of sharks and rays only began in 2017,’ says Wongibe. ‘It was during my internship, which focused on the protection of the West African manatee, while I was pursuing my MSc. It was then that I and my peers encountered and reported the scalloped hammerhead shark and the devil ray. I didn’t pay much attention to them, however, as I was focused on collecting data for my thesis. Unfortunately, these species were not part of our school curriculum and rarely did a teacher mention them, if at all. Throughout my BSc and MSc studies, I was probably the only one in my cohort focusing on marine science, and specifically on sharks. There is a general lack of awareness about marine biodiversity in Cameroon, in part because many people are afraid of water, but also because there is a lack of capacity and prioritisation of marine conservation and ecology at school and university.’

Like Cyndi, and much of his entire community, Wongibe had never even heard of Jaws. In true shark enthusiast fashion, though, he responds, ‘I had never seen Jaws until I received your e-mail. I searched for it online and watched a portion on YouTube, and now I would love to see the complete movie!’

In Ghana, SOSF Conservation Fellowship recipient Dr Issah Seidu grew up far from the coast and unaware of his country’s shark and ray diversity. ‘I had little exposure to the marine environment. The ocean and the biodiversity it holds felt distant and unfamiliar. I had no knowledge of the marine ecosystem, let alone the presence of sharks. It wasn’t until after I completed my BSc degree that I began to learn about these fascinating creatures and their role in our waters.’ His community, he explains, were not particularly interested in foreign films and so, even though a quick IMDb search shows that Jaws premiered in countries like Gabon, Equatorial Guinea, South Africa and Lesotho between 1975 and 1978, Issah is pretty convinced most had neither heard of nor watched the movie. ‘I wasn’t aware of the movie when I first started working on sharks,’ he adds. ‘I only watched it after I had developed a genuine interest in studying them.’

Fear was Dr Edéya Pelebe’s first introduction to sharks in his home country of Benin. ‘I was not interested in sharks when growing up, but I can remember the common belief in my living community (village) was that sharks are very dangerous and we have to fear them.’ He has gone on to become the president of Benin-based NGO Nature Ecologique (ECO-NATURE) and is a researcher and part-time lecturer in aquaculture and aquatic ecotoxicology at the University of Parakou, Benin, and the Africa Centre of Excellence in Coastal Resilience at the University of Cape Coast, Ghana. ‘No, I was not aware of the movie Jaws before I embarked on my conservation and research on sharks. And people in my community focus their attention and interest on bony fish.’ Today, Edéya’s efforts are directed at understanding catch pressure and trade in the Critically Endangered scalloped hammerhead shark. He works to develop the conservation skills of fishermen and fisheries managers to improve management practices and the conservation of the species in Benin.

And fear also wasn’t a hurdle for other researchers around the world who found their calling in shark science, even though it was present in their childhoods too. ‘I wasn’t ever aware of the fact that sharks are present in the territorial waters of my country,’ says Nahla Kahn, a SOSF project leader based in Bangladesh. ‘I have always found sharks to be fearsome creatures and I wasn’t really interested in them until I started studying and dissecting them as a zoologist.’

That combination of revulsion and reverence is a common theme and, for many, it was present in the stories of sharks throughout childhood quite independent of Jaws and its influence across Western popular culture. And the varied experiences of people show how localised, and individualised, our perceptions and their shaping can be. Quite unlike Amani and James, Nahla explains, ‘The movie Jaws was not “the thing” to draw my attention to sharks. It did for many people in my community, but not me. That’s probably because I was miles away from Western pop culture while growing up and I think I still don’t follow current culture that much.’

In the end? The result for Nahla is the same as for Amani, James and the likes of Cyndi, Wongibe, Issah and Edéya: a life dedicated to understanding and protecting sharks and rays, based on fascination and fear – this time for their survival and, by extension, our own.

Photo © Byron Dilkes

What do we really want to say about sharks?

For Amani the world needs more marine biologists – or at least, more people drawn to the ocean and passionate about understanding and protecting it. ‘I think it’s easy to assume or believe we know everything about sharks and the ocean as a whole, when in reality we know so little. Having more people in this field only improves our ability to learn and discover more.’

‘Having more people trying to make a difference and giving a voice to endangered marine life can only help,’ agrees James.

It is not a direct correlation, but perhaps no coincidence, that in the 50 years since Jaws was released, the consensus across all credible scientific information is that we are facing biodiversity loss at the scale of a sixth mass extinction event and are experiencing rapid (and accelerating) changes to our global climate that threaten the fabric of our societies and our survival as a species on this planet. Reflecting on Jaws prompts us all to revisit our relationship with nature and to examine the disconnect that allows us to destroy the life support system on which we all depend.

In 2022, more than 190 countries adopted the Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework, which outlines a vision of the world living in harmony with nature where ‘by 2050, biodiversity is valued, conserved, restored and wisely used, maintaining ecosystem services, sustaining a healthy planet and delivering benefits essential for all people’.

There is much that needs to be done to achieve this vision for our future. Arguably, an important part of that is revisiting the stories we tell ourselves and each other about nature.

There is a world that was entirely unfamiliar with, and unaffected by, Jaws and its infamy – and yet, these places continued to produce shark researchers and advocates, and also rely on shark fisheries, tourism, and trade. There is a world that was rocked by the same film, its influence taking hold of the unarticulated and complicated idea of sharks in our collective consciousness and resulting in both an inspired generation of changemakers, and exploitation rooted in fear. Two things can be true at once. But what happens when we grant and guide access to nature – to sharks – early on in life? Proximity, connection and experience all shape the stories we grow up with – and, therefore, determine the distance we need to travel over the course of our lives to reach the same goal: a passion for protecting our common heritage across this planet.

‘I was interested in sharks when I was little,’ says Valentina Hevia-Hormazabal, a scientist who hails from Chile and is working to understand how best to improve the survival chances of unborn shark and ray embryos that wash ashore in mass egg-case strandings.

‘I studied at a rural school in Pisco Elqui (in the interior of the Elqui Valley), which in those years had very few students. And my natural sciences teacher (Miss Mirna Rivera) often taught us outside the classroom and was always looking for information that could answer our questions, regardless of whether she was in the classroom. So, at one point, an uncle arrived and found a fossilised shell, and many questions arose, including ones about sharks.

Although they scared me a lot because of the stories that had been told, I was very intrigued by how it was possible that they existed long before other animals.’ Jaws, she says, was popular in Chile in the 1990s – but there is something to be said for Valentina’s experience of an adult taking the initiative to guide and mentor her innate curiosity about the natural world.

For Professor Rodrigo Domingues in Brazil, proximity to the beach and access to the ocean in the form of surfing as a teenager first roused the idea that he shared the water with sharks. For him, this connection ultimately shaped his advocacy today. ‘I was familiar with Jaws and still hold that it ultimately conveyed a message that goes against what I believe in and advocate for today. In reality, sharks are the main victims in our story, yet they play a crucial role in the health of marine ecosystems.’

Amani agrees. ‘I hope that anyone who saw the film today would understand it as entertainment rather than believe it to be factual or true. The thing that really made this movie harmful to sharks was people watched that movie and then conflated the interactions of this fake shark with the behaviour of real sharks. I would hope now there are enough resources available for people to be able to learn about the real behaviour of sharks and understand that Jaws as a film is completely fake.’

The way we speak about sharks has undoubtedly shifted in the 50 years since Jaws. ‘I hope that a modern audience would watch it, and appreciate it as a brilliantly made film. But I hope that people would watch it today and think – wow, look at how differently we viewed things then,’ says James. The film is, from this conservation perspective, a time-stamp; a record against which we can track our progress.

Artwork by Kelsey Manners Dickson | © Save Our Seas Foundation

The question is whether the shift is sufficient, and quick enough, to tackle the complexity and variety of issues we face in fighting for their persistence today. ‘My kids have such a range of books, ranging from beautiful facts and illustrations to sweet picture books (although I think we’re still a long way from having enough!),’ says James. ‘The portrayal of sharks has certainly shifted across a variety of media in the past 50 years. My kids love Octonauts, for instance, and quite often the species that these animated cartoon characters set out to investigate is a shark or ray – and fantastically diverse and unusual ones, at that.’ James adds that anything from a white shark to the extraordinary velvet-belly lanternshark could end up in an episode – a giant leap forward for improving our storytelling of the ecological importance and functional diversity of these animals.

agrees Amani. ‘Then when I think about the actual information being covered when I was younger versus now, I realise how narrow the scope was when I was a kid. It was always programmes about shark movement and tracking, whereas now there is such a huge diversity of research that is featured. I think it’s amazing how much the scope has broadened because there’s so much cool research going on that we now get access to!’

Perhaps we’ll finally move to a place where sharks are neither gods nor demons, but animals – species we share the planet with – and ones that have swum these oceans since before there were trees on land. As we move forward, tackling the major conservation issues of our time, we will still need more stories about sharks: their diversity, their roles in our ecosystems, and their importance to our lives. Equally, we will need the tapestry of tales to be as rich as the voices that research them and rely on them. And if the international chorus of voices that now add insight and effort to conservation are anything to gauge by, we will move to a future where individual experiences, local connections and ancestral kinship can have global impact.