From Treasure Island to treasure hunt

As mentioned in my last blog post, Isla Grande was my first field site in Colombia, but I was lucky enough to visit more islands. In this blog, I speak about some highlights from the most interesting places visited.

A fisherman poses with his fishing gear and boat, with Cartagena in the background. Photo © Julian Rodriguez

As part of my research project in Colombia’s Natural National Park Corals of Rosario and San Bernardo, I have been interviewing fishers with the Save Our Seas Foundation in Colombia and at the same time deploying BRUVs for Global FinPrint. BRUV stands for Baited Remote Underwater Video survey, which entails setting up a GoPro camera underwater with some bait to attract passing fishes and ‘catch’ them on camera. This method of surveying reef fishes is less intrusive than others and enables us to establish a baseline of the relative abundance and diversity of sharks and rays. After my first field site, Isla Grande, I was lucky enough to sample in Isla Tesoro (literally ‘Treasure Island’) for Global FinPrint. This island belongs to the president of Colombia and we had to get permission from him to work there. Of course, this island is under surveillance and more strictly protected than any other. No one, including artisanal fishers, is allowed on the reefs or on the island unless they have been granted access by the Colombian military.

While doing an initial snorkel to find a perfect spot for the camera, I could see at once that Tesoro’s reef seemed very vibrant, full of coral and fish life. There were more corals and fishes than I had observed previously at Isla Grande, and in fact the first shark spotted on our cameras during this trip was a lemon shark at Tesoro. Unfortunately, I was not able to interview any fishers at Tesoro because no one is allowed to live there, although I found out from my other interviews that artisanal fishers would sometimes sneak away to fish at Tesoro at night when no one could see them.

A field assistant, Hans, puts the GoPro on the BRUV. Photo © Julián Rodríguez

One kilogram of oily fish bait is put in a cage right in front of the GoPro. Photo © Julián Rodríguez

When we put the camera in the water and then again when we pick it up, we take many environmental measurements, such as temperature, flow and salinity, to see if they influence whether a shark or ray appears on camera. Photo © Julián Rodríguez

Deploying a BRUV, with Tesoro in the background. Photo © Julián Rodríguez

One of the team has to free dive down with the BRUV to make sure that it doesn’t damage any corals, that it is stable and that it is facing down-current. (Credit to Julián Rodríguez)

The first shark seen on our cameras was a lemon shark at Tesoro. Photo © Camila Cáceres

Múcura and Santa Cruz del Islote

After finishing sampling at Isla Grande and Isla Tesoro, the two sites we were surveying in the northern part of the park, we packed up our entire camp and moved to a different park headquarters on Isla Múcura, an island in the San Bernardo Archipelago in the south. Although Múcura is not quite as large as Isla Grande, it does have a lot of tourism activity because of a luxury hotel on the island and another on nearby Santa Cruz del Islote.

Santa Cruz del Islote is famous for being the most densely populated island on earth. It has been estimated that about 1,200 people live on El Islote, although the islanders themselves denied this during my interviews with them. Many said that the government had made a mistake because it conducted the census at Christmas time, when there are many tourists and a lot of outside family members come home for the holidays. Most of the islanders seem to agree that a more accurate estimate would be about 700 inhabitants in an area of .012 square kilometres. With 97 houses on the island, that’s an average of seven people living in each house. It is rumoured that all the families on the island share only six surnames. Although it would seem that living on an island so densely populated would be a problem, observations suggest that those living on El Islote are better off than the residents of other islands.

Santa Cruz del Islote, the most densely populated island in the world, with an estimated 97 houses. Photo: Google Images

Thanks to a programme in collaboration with the Japanese government, El Islote received solar panels that supply all the energy needed on the island, so its residents are able to have more refrigerators, TVs and other technology than other islanders. There is also a boat that brings food to the island once a week, enabling Islote residents to buy fruit and protein from the mainland – a perk that is not available on other islands. Even if residents have to go to nearby islands like Múcura or Tintipán for jobs, they still choose to live on El Islote and come home to it at the end of the day because of the many amenities available there.

You can see the Japanese solar panels that power all of El Islote as well as Múcura in the background. Photo: Google images

Although El Islote has received a lot of attention and aid on account of its dense population, there can be no denying that the islanders rely heavily on all ocean resources and that fishing is still their main means of acquiring food and money. Everyone we approached on the island identified themselves as a fisher and I was able to walk around freely and interview almost everyone I met. Santa Cruz del Islote was definitely the highlight of the project for me, since conducting interviews here was not only easier than anywhere else, but also more interesting due to the dynamics on the island.

Cartagena

After interviewing fishers on Múcura and El Islote and deploying BRUVs around the remaining islands (Tintipan, Mangle and Panda), we returned to mainland Colombia for the last leg of our trip. Although I wanted to interview as many artisanal fishers as possible on their native islands, I was also interested in seeing what products were being brought to Cartagena and talking to the fishers who had caught them. Most of the time, artisanal fishers from these islands take their catch home to feed themselves and if they have a little bit extra they either give it away or sell it to another fisher. However, when they are lucky (for example, one day while I was there they caught one ton of black skipjack tuna Euthynnus lineatus), all the fish is shipped to Cartagena immediately and then exported abroad the next day.

In Cartagena, the biggest and most renowned fish market is Mercado Bazurto. It is not like other street markets, as you can see when you arrive. Bazurto is full of locals, with fruit and fish being sold that only really appeal to local people. The market is loud, hectic and smelly, and you can easily get lost and end up on the wrong side of town if you are not careful. We walked around for a while, talking to as many fishers as we could and trying to spot elasmobranchs for sale. Unfortunately, the few sharks and rays we were able to find had been mostly decapitated and cut up into chunks, which made it very difficult to identify them. On one occasion I witnessed a very well dressed man (he looked like he had plenty of money) buying shark fins. Even though buying and selling shark fins is legal, cutting those fins from the shark without bringing in the rest of the body is not. For that reason, people are still very cautious about buying or selling shark products, so when the man noticed me watching him he quickly paid and ran off. We continued walking around the market and talking to fishers for the rest of the day, and even though everyone displayed their catches with pride, we did not witness more shark fin sales. Ironically though, we did see a fisher clean a shark and throw one of its fins to the side, where it remained the whole day, unnoticed in a pile of trash.

A spotted eagle ray for sale at Bazurto. Many fishers consider spotted eagle ray to be an aphrodisiac. Photo © Julián Rodríguez

Slices of shark meat for sale at Bazurto. Finding the fish like this made it incredibly difficult to identify the species. Photo © Julián Rodríguez

A shark torso on display for people to buy slices of meat. Photo © Julián Rodríguez

Shark oil was also sold at the market. Locals believe that putting a few drops of the oil in a water bowl and leaving it to evaporate will clean the air and help to combat respiratory diseases like asthma. Photo © Julián Rodríguez

An unidentified shark fin left on the floor as trash in the market. Photo © Julián Rodríguez

Combining as it did visits to 11 different islands, including the president’s island and the most densely populated island on earth, and to the city of Cartagena, the hub of fish sales and export in the Colombian Caribbean, this research project has been the hardest yet most rewarding of my life. Collecting 200 fisher interviews and deploying more than 250 cameras in five weeks (with a hurricane passing through while we were busy) was not easy, but I am happy to say I was able to accomplish all my goals. My research project was the first of its kind, the first shark research project in the National Natural Park Corals of Rosario and San Bernardo, and I could not have done it without the help of my collaborators and the Save Our Seas Foundation.

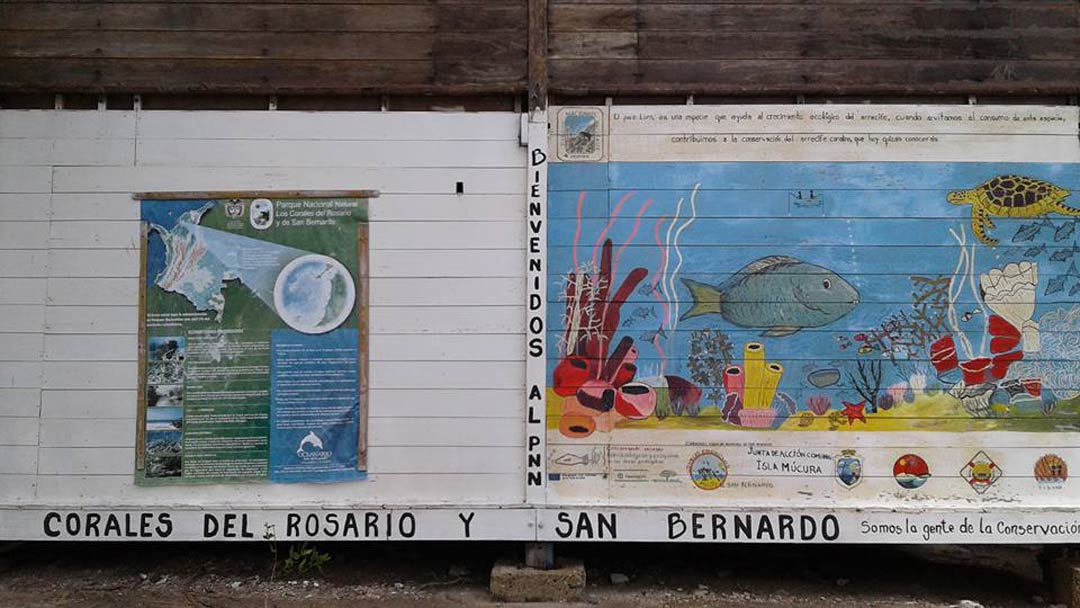

The sign at the entrance to the park in Múcura was painted by local children. Photo © Sandra Eöry