Investigating Isla Grande

When fishers were forced to stay home they spent a lot of time fixing their nets, which gave us the perfect opportunity to sit next to them and talk. Photo © Julián Rodríguez

My first field site in Colombia’s Natural National Park Corals of Rosario and San Bernardo was Isla Grande. This beautiful island covers two square kilometres (0.8 square miles), which makes it the largest island in the park and explains its name. It has a permanent population of about 800 people, but due to its beauty and its proximity to Cartagena (about an hour by boat) it is a hotspot for tourism, with hundreds of tourists visiting every month. There is an aquarium on Isla Grande that attracts day-trippers from Cartagena and there are also a number of eco-hotels that accommodate visitors from all over the world, so at any given time the local population may be doubled. Yet the island is small enough that there are no roads or cars, only footpaths. Like the other islands in the park, Isla Grande is home to typical Caribbean flora and fauna, including coconut, palm and ceiba trees, white, red and black mangroves, and frigatebirds and herons.

The view from the dock as we arrived at Isla Grande. The stairs up to the island lead directly to the entrance of the Natural National Park Corals of Rosario and San Bernardo. Photo © Sandra Eöry

In order to arrive at one of my field sites, Baru, I have to pass many red mangroves before the view of the town opens up. Photo © Julián Rodríguez

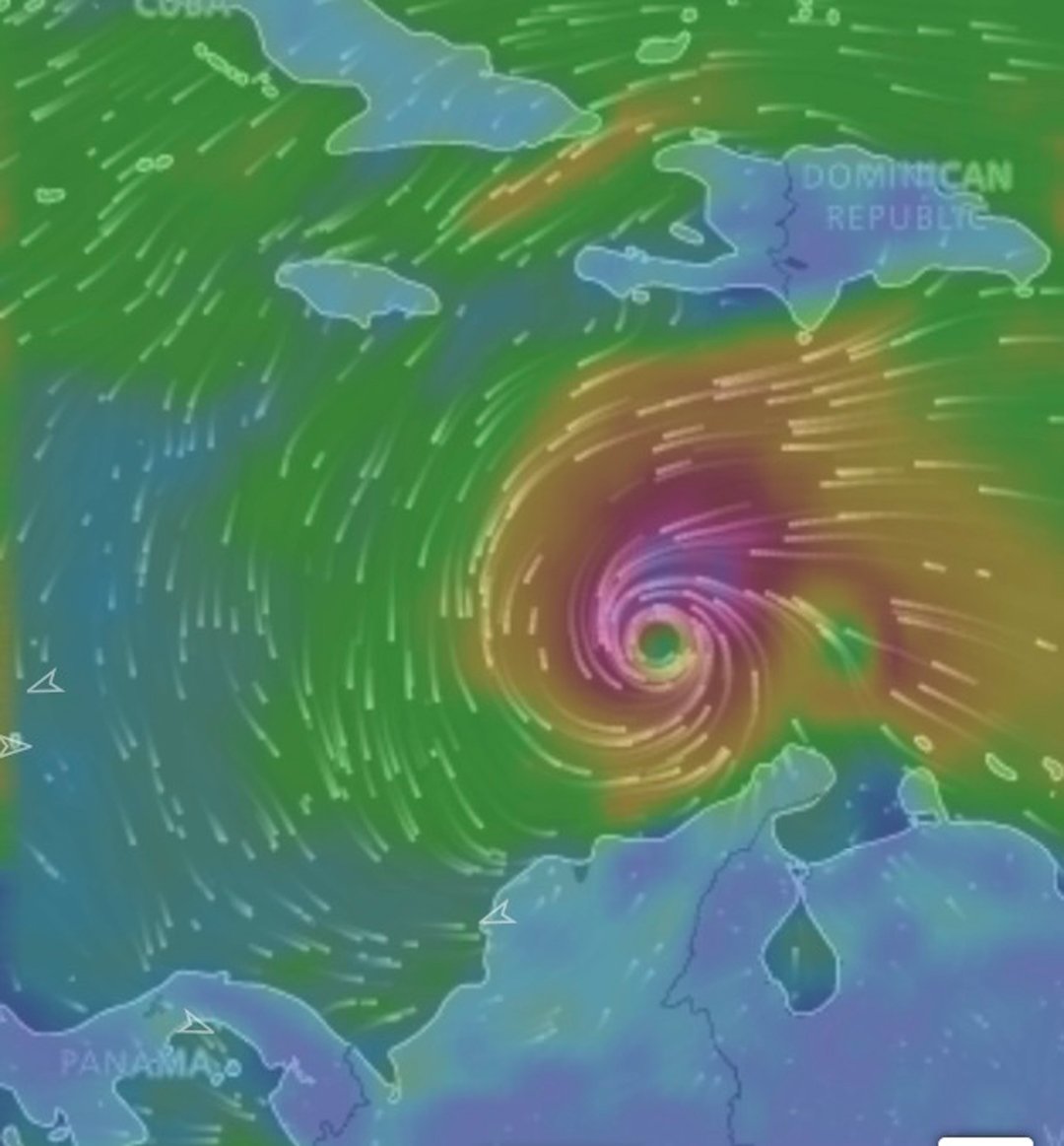

Hurricane Mathew came through soon after we arrived at Isla Grande. Even though the storm was not close enough to cause any significant damage to the islands, Cartagena halted all boat traffic between the mainland and the islands, as well as between islands. It was extremely windy and it poured with rain for about five days, which ended up working to our advantage because this meant that fishers were at home and had plenty of free time to talk.

Map of Hurricane Mathew near our field site.

Fishermen always help each other to fix their gear. Photo © Julián Rodríguez.

Fishing gear is damaged almost daily and fishers have to constantly keep up with their mending. Credit to Julián Rodríguez.

Sometimes if a net cannot be fixed, the fishermen make a new one from scratch by hand weaving it. Photo © Julián Rodríguez.

The first fisher I interviewed was Bernardo, and he is a very special man for several reasons. Firstly, he is over 70 years old, which is quite rare for the islands. Secondly, he considers himself retired from fishing, which is also very uncommon: artisanal fishers almost always continue to fish, even if it is in addition to other income-generating activities. And thirdly, he switched to research and conservation efforts in his old age. Bernardo felt that he had spent his life relying on the ocean to provide him with food and income for his family; now, in his senior years, it was time to give back and provide for the ocean in return. He had noticed that the quantity and quality of coral and fish life have decreased over the years and was worried that there were too many fishers on the islands. Unlike many of his peers, Bernardo developed a close relationship with the park authorities and started collaborating with them in numerous conservation efforts. The main project he is involved in is the park’s turtle nest monitoring programme. Bernardo’s speciality for most of his life had been catching yellowtail snapper, wahoo and little tunny with a hand reel, but now he found that he has a natural talent for spotting the nests of green and hawksbill turtles.

Bernardo uses a wooden stick to search for turtle nests on the beach. He identifies by sight sandy areas that look as if they may contain turtle nests, and then digs around with the stick to find the eggs. Photo © Diego Duque.

If Bernardo finds a nest in an area that is not safe from animals or tourists, he digs a hole in a more suitable spot on the beach and transfers the eggs. Photo © Diego Duque.

Sometimes when Bernardo finds a nest, the turtles have already hatched and only eggshells are left. He still digs out the nest and counts the shells in order to calculate how many turtles hatched. Photo © Diego Duque.

Bernardo is famous among fishers for his appearance in the park’s book about the environment around the islands. Photo © Julián Rodríguez

What I found most interesting about my conversation with Bernardo was how his actions and thoughts changed so radically when he grew older. Although he still enjoys spending time on the beach and gazing at the ocean, it is nearly impossible to get him on a boat. After so many years of spending time outdoors in his canoe, Bernardo shies away from being under the sun or in salt water. I had always thought that even though one may tire of the trials and tribulations of fishing and working hard in the sun, the love of being out on the water would never fade. But that’s not the case for Bernardo. He seems to have had his fill of boat time, sun time and fishing time and is now turning to activities he had never considered before. More than anything else, this highlighted to me that anyone’s mental perspective can change if something inside them clicks. Bernardo told me that once he had managed to build his house and raise his children, he no longer felt the need to continue fishing. After having worked so hard his entire life to provide for his family, he finally turned to taking care of what had provided for him his entire life: the ocean.