Sharks on the urban edge

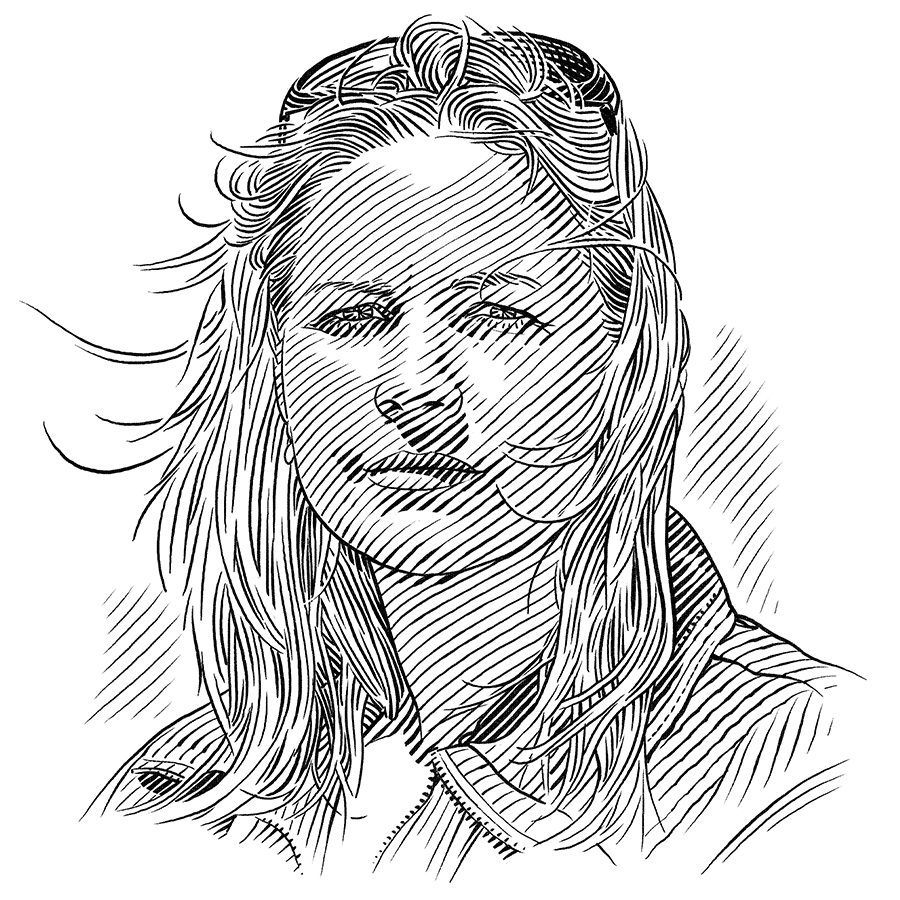

False Bay is home to one of the world’s largest white shark populations and a growing human community. This creates a number of challenges for both people and sharks. Alison is finding out how these apex predators shape the bay and what would happen if they disappeared.

‘My goal is to be a marine biologist.’ This is the hand-made banner that I displayed above my desk all through high school. I have always wanted to be a marine biologist and was fortunate to have parents who fostered my love for the ocean. When I was very young I used to accompany my dad on boat trips to harvest crayfish. We would spend hours at sea, deploying nets and waiting for the crayfish to climb inside. When we retrieved the nets, it wasn’t only crayfish that we found, but small shysharks too. The little sharks would curl up...

Shark research component of the Shark Spotters programme

The key objective of this research is to understand the drivers, both environmental (e.g., water temperature) and biological (e.g., prey availability), of white shark presence in False Bay and define the role of this apex predator in a temperate ecosystem. We will use the results to improve management of critical habitats, and in shark safety strategies and awareness campaigns.

It has been established that there is high spatial overlap between human recreational water-users and female white sharks in False Bay during the warmer months of the year. The white shark’s seasonal distribution along popular recreational coastlines, natural opportunistic predatory tactics and large size increase the potential for human-shark conflict. This results in the challenge of conserving a threatened and protected apex predator in conflict with humans.

Although Cape Town is a white shark conservation success story, conflict between humans and sharks is likely to continue, due to human population growth and increased coastal development. Therefore, to maintain the balance between white shark conservation and public safety, it is imperative that we have a strong scientific foundation for white shark ecology, coupled with non-lethal mitigation methods and supported by a comprehensive education and awareness strategy.

Previous research has identified False Bay is a critical area for white shark conservation because both sexes, across a range of sizes, show high fidelity to the bay. Furthermore, it’s been shown that Seal Island hosts one of the world’s largest white shark populations. The past 10 years of research has described the spatial ecology of white sharks in False Bay and identified the sites and times of high and low shark presence and activity. In autumn and winter, males and females aggregate around Seal Island where they feed on young-of-the-year seals. In spring and summer, there is marked sexual segregation: females frequent inshore areas and males are seldom detected in the bay. This research has added substantially to our knowledge of white shark ecology and conservation challenges. However, what drives this behaviour, especially in inshore areas, is still not well understood.

Previous research demonstrated that the primary function of Seal Island is most likely as a feeding aggregation site. Over the past nine years, sightings per unit effort have varied across years; some years have had relatively lower numbers of sightings, and others have had higher numbers of sightings. What drives this annual variation is not well understood. It is also important to understand the primary function of this inshore region for white sharks, especially maturing females, because the area is heavily affected by anthropogenic disturbance, such as fishing, pollution and coastal development.

A major gap in our knowledge is an understanding of the ecological role of white sharks in local ecosystems. Predators can shape the ecosystems in which they live in a direct (lethal) way by reducing prey densities or in an indirect way (non-lethal) manner as anti-predator behaviour may manifest as changes in resource use by prey.

The aims and objectives of this project are to:

- Monitor white shark presence and distribution in False Bay across different habitats and seasons, and compare their behaviour, e.g., swimming depth and speed, in different habitats to understand how the sharks use them, i.e., for feeding, resting or socialising.

- Monitor population demographics (size and sex ratios) and dynamics, across seasons and years at Seal Island and inshore.

- Monitor trends in sightings and population status over time to determine whether the population is stable, increasing or decreasing.

- Identify environmental conditions affecting white shark presence and distribution. Additionally, test the hypothesis that white shark presence inshore during spring and summer is higher when the water is warm (≥18 °C) and during the phase of the new moon. We will compare this with behaviour observed at Seal Island.

- Identify prey availability (diversity and abundance) across different habitats and seasons in False Bay. We will test the hypothesis that white shark presence is related to an increase in abundance of teleost and chondrichthyan prey in spring and summer months.

- Identify the diet of white sharks, their trophic position and food web interactions. Define the ecological role of white sharks in False Bay to understand the top-down control they exert on local ecosystems, and ultimately be able to predict what would happen to the ecosystem if their populations declined significantly.