Secret lives of silky sharks

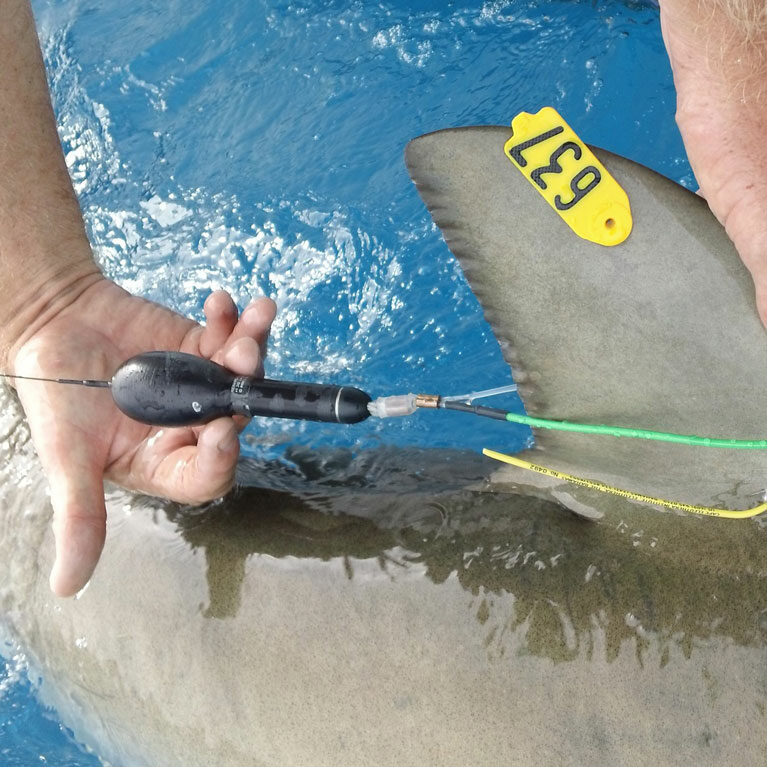

Brendan is satellite-tagging silky sharks across the western central Atlantic, Gulf of Mexico and Caribbean to understand where these sharks are swimming. He is also analysing their gut contents and stable isotopes, all in a bid to document their place in the food web and to support silky shark management and recovery across the region.

As a kid, if I went out to walk by the water I’d eventually end up in it. Creeks and rivers in Kentucky gave way to tide pools along the rocky coast of south-eastern Maine and eventually the sea-grass beds and fishing piers of Pensacola Beach, Florida. Before I could reach the pedals to adjust our kayak’s rudder, my mom would push me off the beach into Santa Rosa Sound and tell me to bring back dinner. I’d paddle our sit-on-top a mile or two down the coast to jerk crystal minnows across blades of turtle grass and eventually make...

Characterizing the horizontal and vertical movements of silky sharks in the Caribbean and western Atlantic

Our objective is to document the horizontal and vertical movements of silky sharks across all life stages in the western Atlantic, Gulf of Mexico, and Caribbean regions. We will identify habitat use patterns, highlight areas of importance (e.g. possible critical habitats), and link environmental variables to movement data.

The silky shark remains the second most common shark caught as bycatch globally, despite being listed on CITES Appendix II, prohibited in some Atlantic longline fisheries, and protected in the Bahamas Shark Sanctuary. Fisheries management organizations currently lack the information needed to properly manage this species and promote population recovery. A rebound to pre-industrial levels is possible, however, as evidenced by signs of increased abundance in U.S. waters in the past two decades. As silky sharks have a moderate intrinsic rebound potential among shark species, and management frameworks and trade restrictions are already in place, the conservation of this species is very achievable.

Conducting this research will bring us closer to that goal by informing species-specific and ecosystem-based management plans. Our research will therefore make a significant contribution to the improved status of this iconic shark’s populations.

Overfishing and low rates of population growth have led to an estimated 46-50% reduction in silky shark catch rates in the northwest and western central Atlantic. It has been suggested that a population reduction of 95-98% has occurred over three generations, leading to a species assessment of ‘Vulnerable’ by the IUCN Red List in this region.

Despite this vulnerability, limited data exist on silky shark movements in the Atlantic. Those that do exist are based on conventional tagging programs that suggest large-scale migrations between the WA, Gulf of Mexico (GoM), and the wider Caribbean. Fine-scale movement data derived from satellite tags have only been collected for three females tagged in Cuban waters; two of those tags recorded vertical movement data for around one month and generated unreliable tracks and the third transmitted only four locations. Genetic analyses agree with extensive mixing across the region and suggest that WA and GoM silky sharks make up one stock, highlighting the importance of obtaining movement data across broad spatial and temporal scales in order to better inform management plans internationally.

Further, data are lacking on silky shark trophic ecology, precluding their incorporation into ecosystem-based management schemes (a pressing goal for many fishery management organizations). Limited data do exist from studies in the Pacific and Indian Oceans, where silky sharks were classified as opportunistic predators that feed on a wide prey base, often utilizing fish aggregation devices to increase their prey encounter rates. While these data are informative, they should be collected in the Atlantic for use in space-based models to avoid the misrepresentation of food webs.

- Document the horizontal and vertical movements of silky sharks in the Western Atlantic, including a focus on the following for all life stages: depth range and thermal preference, diel vertical migratory behavior, vulnerability to pelagic longline gear, residency time in The Bahamas Shark Sanctuary, and ontogenetic shifts in habitat use.

- Investigate the trophic ecology of silky sharks in the Western Atlantic, including a focus on the following: changes in diet across ontogeny, relative contributions of different carbon sources to juveniles and subadults, and diet analysis through fecal swab, stable isotope, and stomach content analysis.

- Train high school, undergraduate, and post-graduate students in research techniques and in the fields of spatial and trophic ecology.

Public presentation at MODS: Save Our Seas Distinguished Speaker Series : Shark Conservation and Tagging