A genetic tool to help monitor sharks and skates in the North-east Atlantic

Catherine is intent on helping better monitor flapper skates and spurdogs in the North-East Atlantic. To do so, she is developing a tool that can use DNA from egg cases, skin mucus and historical samples to analyse the diversity, kinship, connectivity and adaptations of these species. She and her team are identifying a subset of the most informative genetic markers for each species, which will help inform conservation strategies and MPA management for both species in Scottish seas.

Growing up in the middle of England away from the coast a trip to the seaside was a treat; unforgettable days peering into rockpools, seeking out their darting inhabitants hiding amongst the seaweed. My family house was old, so observing indoor wildlife eventually led to an academic interest in mice as models of evolutionary genetics during a PhD at London University. This led to studying the genetics of more challenging, less well characterized species at Oxford University. Research fellowships on aquatic species allowed me to study genetics of blood flukes and tropical freshwater snails in Africa; figuring out why...

Genetic monitoring tool for North-east Atlantic elasmobranchs to assist conservation and management

To establish a practical genetic monitoring tool for rapid, high-throughput genotyping that is accessible to researchers monitoring flapper skate and spurdog. These standardised marker panels will produce additive datasets in perpetuity, providing invaluable repositories suitable for temporal and cross-laboratory comparisons and will permit ongoing monitoring across multiple legislative authorities.

As high-value fisheries species, many north-east Atlantic elasmobranchs have been significantly impacted by targeted fishing and by-catch. As a consequence of their low intrinsic rate of increase, recovery of their populations can be very slow and in some species a significant proportion of their valuable genetic resources may have been lost forever. This makes genetic monitoring to assess the variability and connectivity of populations essential components of management for identifying the best practices that are likely to benefit elasmobranch conservation.

Marine protected areas are increasingly used as a tool to promote conservation across locations chosen for their habitats that are likely to be important to species of conservation concern. Elasmobranchs in the north-east Atlantic have site-associated behaviours, which means they stand to benefit greatly from marine protected areas, as will other species in the local ecosystem in which these top predators play a pivotal role. The ‘Loch Sunart to Sound of Jura’ marine protected area in west Scotland was chosen to protect the flapper skate, one of two ‘common skate’ species now recognised as endangered. Large numbers of skate in the area indicated important habitats and it was hoped that protecting this population would allow connectivity with others, as the larger the interbreeding unit, the better it is able to maintain the valuable genetic diversity that allows the species to adapt to environmental change. The spurdog, an endangered elasmobranch, is incidentally protected in the same protected area and its genetic health and connectivity also need monitoring. Our initial work suggested that the flapper population in the marine protected area comprised individuals with unique maternally inherited genetic components. This could reflect that females are not breeding or travelling much beyond the protected area and that they are more isolated than initially hoped, thereby limiting the area’s effectiveness as a conservation tool that maintains genetic variation as part of a regional population. Genetic markers with a higher resolution suggest there is some connectivity with other populations, but this requires further investigation and the results need to be made capable of being interpreted by future generations of conservationists. Assessing variation with a monitoring tool of a smaller panel of highly informative flapper skate and spurdog markers should allow new technologies to standardise genetic assessments, removing any bias of individual laboratories and operators. Placing samples and data in a free-access national repository will encourage the formation of larger working groups to monitor further flapper skate and spurdog populations and make it possible to determine the effectiveness of marine protected area management.

- To identify a subset of the most informative genetic markers for each species, derived from larger genome datasets, and develop a monitoring tool that will enable kinship, genetic diversity, population connectivity and adaptive patterns to be analysed.

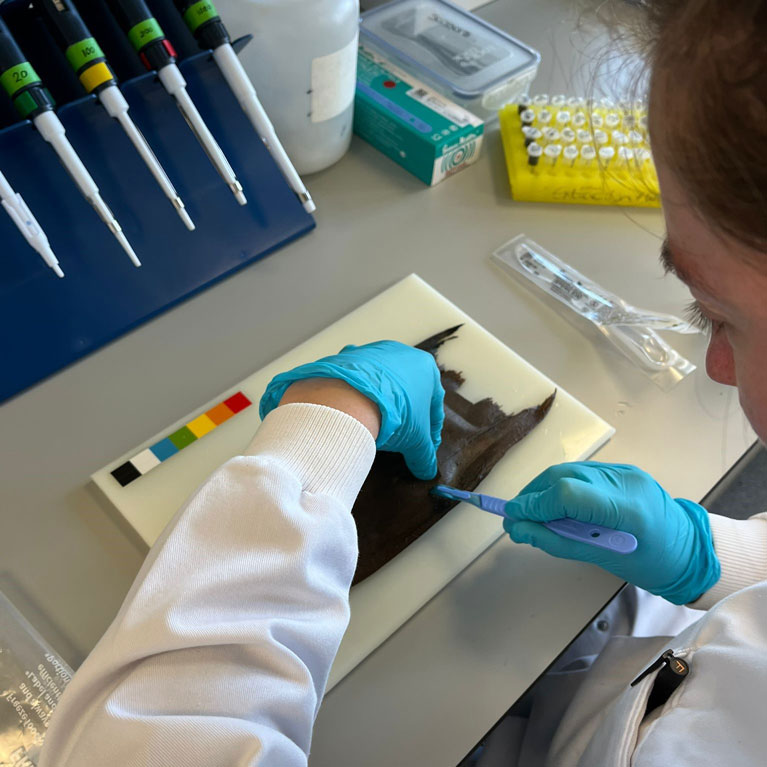

- To evaluate the performance of the new monitoring tool for different tasks compared with alternative genome-wide markers and to trial the monitoring tool on DNA sources of poor quality/quantity, such as flapper skate egg cases and skin mucus and historic material. If successful, this will enable individuals to be linked to nurseries and sample sizes to be increased. Museum specimens may enable historical changes in genetic diversity to be assessed.

- Together with collaborating NGOs, to create a manual for consideration by policy-makers and elasmobranch conservation bodies, illustrating how this methodology can be used in conservation management and the monitoring of threatened species.

- To deposit a dataset based on available and new samples that will form the basis of an additive data repository for standardised genetic information about these species.

Summary of main research results/outcomes

Legacy datasets, invaluable for endangered species conservation, require temporally reproducible methodologies. As a first step, genome-wide nuclear SNPs* from flapper skate and spurdog were used to determine population structure and kinship within and outwith a coastal Northeast Atlantic (NEA) Marine Protected Area (MPA). Although populations of flapper skate were genetically diverse, the MPA contained the greatest number of relatives, had less connectivity with other populations and so seems unlikely to act as a source of migrants replenishing unprotected areas. Spurdog had little population differentiation, but a large aggregation contained a high proportion of relatives, suggesting long-lasting associations. Trials of allele-specific SNP panels (derived from genome-wide data) reliably identified individuals, providing potential monitoring tools for both species. Mitochondrial haplotypes of flapper skate egg cases showed nursery areas are used by multiple females from across the Northeast Atlantic. These advances promise genetic monitoring tools for other Chondrichthyans of conservation concern.

Once techniques have been further refined, continued genetic monitoring of flapper skate egg cases in the two egg-laying sites assessed here should continue, as well as for other currently identified or future egg-laying sites throughout Scotland (subject to Ministerial derogation). Current information suggests that eggs laid at both egg-laying sites on the West coast of Scotland are diverse, indicating several females laying at a site. Females laying at Loch Melfort are likely to be associated with the nearby area, but females laying within the RRL MPA may be travelling further, contributing to higher genetic diversity. To understand these patterns in more detail, as well as explore how many mothers may be utilising a site, how often, and whether they exhibit natal philopatry, increased sample sizes are required, and more research is needed to refine the DNA extraction and sequencing methods further.

* Single nucleotide polymorphisms, frequently called SNPs (pronounced “snips”), are the most common type of genetic variation among people. Each SNP represents a difference in a single DNA building block, called a nucleotide.

Published Papers:

Schwanck, TN., Wood F., Frost M., Thorburn J., Dodd J., Donnan DW., Wright PJ., Noble LR., and Jones CS. High relatedness within a population of the critically endangered flapper skate (Dipturus intermedius) suggests limited connectivity of a marine protected area. Submitted Heredity

Wood F., Schwanck, TN., Thorburn J., Meharg, A., Noble LR., and Jones CS. Genome-wide analyses reveal familial relationships within spurdog aggregations. In prep for Marine Ecology Progress Series.

Wood F., Schwanck, TN., Thorburn J., Meharg, A., Noble LR., and Jones CS. Development of SNP panel assays for genetic monitoring of two endangered Northeast Atlantic Chondrichthyans. In prep for Endangered Species Research.

Wood F., Schwanck, TN., Dodd, J., Thorburn J., Meharg, A., Noble LR., and Jones CS. Chondrichthyan egg case material as a non-destructive genetic resource. In prep for Conservation Genetic Resources.

Wood F., Schwanck, TN., Dodd, J., Thorburn J., Meharg, A., Noble LR., and Jones CS. Use of egg-laying sites by critically endangered flapper skate (Dipturus intermedius) in scotland: insights from egg case material as a non-destructive genetic resource. In prep for Marine Ecology Progress Series.

Wood, F.R. (2024). Genetic monitoring of two endangered Northeast Atlantic Chondrichthyans. University of Aberdeen. PhD Thesis.

Schwanck, T.N. (2022). Assessing genetic diversity and connectivity for conservation of the critically endangered flapper skate, Dipturus intermedius (Parnell, 1837). University of Aberdeen. PhD Thesis (Chapter 3 only).