Homebodies at heart; the movements of reef mantas in the Amirantes

Reef manta rays (Mobula alfredi) are homebodies at heart, keen to keep closer than we’d previously imagined to D’Arros Island and the neighbouring St Joseph Atoll. This finding, part of a new study that details the movements of reef mantas in the Amirante Islands of Seychelles using acoustic telemetry, places emphasis on the importance of this region to a globally vulnerable species. It turns out that while reef mantas wing their way through the Amirantes year-round, a startling 89% of acoustic detections recorded during this four-year study occurred within 2.5 km of the shoreline at D’Arros and St Joseph Atoll. This high site fidelity (that is, the reliance on and preference for this particular site) provides strong support for a marine protected area (MPA) to be established at this location to protect local populations of reef mantas in Seychelles.

Nothing captures the imagination quite like the mobula rays; the gentle swoop of their pectoral fins move them like magic carpets through tropical seas. Captivating as they may be, we still know little of where, when or why these mysterious creatures travel around the remote atolls of the Western Indian Ocean. Without this information, we stand little chance of successfully managing their dwindling populations. In these far-flung seas, the islands where reef mantas aggregate are difficult to access. A challenge to scientists, perhaps, but one that Lauren Peel from the University of Western Australia took up gladly. “When we first started working with the mantas at D’Arros, we knew that the aggregation there was fairly reliable based on previous sighting records we’d received, but we didn’t know how resident the mantas were to D’Arros Island and the wider Amirante region over time.” Lauren’s results, the culmination of four years’ worth of tracking data, were published this month in Marine Ecology Progress Series.

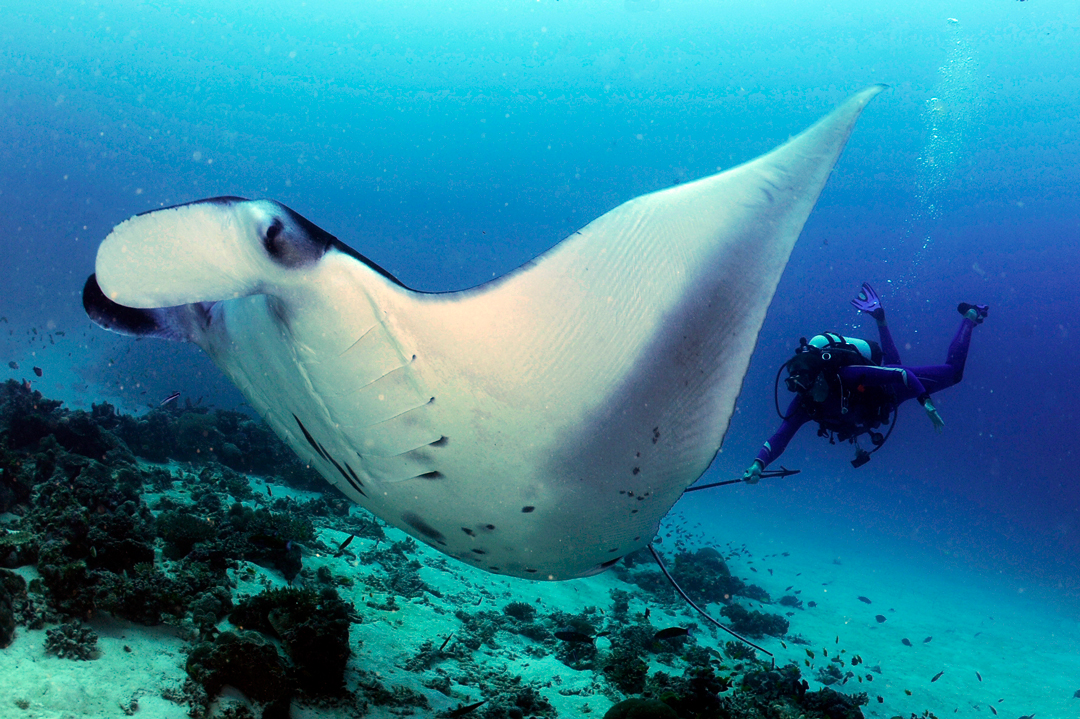

A reef manta ray cruises over a reef at D'Arros Island, Amirantes, Seychelles. Photo © Guy Stevens | Manta Trust

Together with her co-authors, including Dr Guy Stevens (Manta Trust), Dr Ryan Daly and Clare Keating Daly (formerly D’Arros Research Centre), Lauren deployed acoustic transmitters on 42 reef mantas at D’Arros Island. These transmitters allowed the researchers to monitor the movement patterns of each manta ray through 70 acoustic receivers scattered throughout the Amirantes. This Island Group of Seychelles was of particular interest to Lauren and the team: “Reef manta rays are a globally vulnerable species that aggregate at circum-tropical locations around the world. I was drawn to the population in Seychelles because it is unique in the sense that the currently-identified aggregations of manta rays occur at remote locations, away from the populated islands of the country. When we started the Seychelles Manta Ray Project, very little was known about the size of the local manta population, where individuals were aggregating, how far they were moving, and if they were moving between Island Groups of the archipelago. That’s why we really focussed our efforts on the aggregation at D’Arros Island: it was one of the few places in the country where we had reliable reports of mantas aggregating frequently. We wanted to establish how important D’Arros was to the population, how long the mantas were staying in the area, their habitat-use patterns around the island, and make use of as many research techniques as possible to get a better picture of what D’Arros Island means for the manta rays of Seychelles”.

The researchers have reason to worry about where reef mantas are moving: these animals are targeted to supply gill plates to a traditional medicine market in Asia. As a result, their populations have spiralled in recent decades. Mobula rays, the family to which reef mantas belong, face additional pressure from non-target fisheries where they are caught as bycatch: they tend to become entangled in fishing gear in purse-seine and gill nets. Three of the world’s most intensive fisheries that target mobula rays – India, Indonesia and Sri Lanka – are located in the Indian Ocean. Now, reports of mobula fisheries in Mozambique, along the east African coast, and in Pakistan, add urgency to needing to understand where mobula rays move in the Western Indian Ocean. Currently, manta rays are protected on an international scale in Seychelles through conventions like CITES and CMS, but on a national and more local scale, they have no formal protection. That’s why this study was so important, details Lauren.

“We wanted to get an idea of how significant D’Arros Island and the Amirante Island Group are to the life history of these animals, and to examine whether the establishment of marine reserves at these locations would benefit conservation and management efforts for the population”.

When it comes to conservation, and in particular, the design of a marine protected area that works, movement data matter. “Spatial data are critical to improve our understanding of where the mantas are going and where we should be focussing management and conservation efforts” Lauren explains. This kind of information is key to protecting manta rays in their last stronghold areas. “But these data don’t tell us much about why they are travelling to, and aggregating at, those sites. The environmental data that we’ve been collecting gives us insight into this, and lets us examine possible drivers of manta ray movement patterns and behaviour.” For this reason, the researchers measured a host of other factors that might help explain why manta rays are moving to particular areas: the day of the year and time of day, what fraction of the moon was illuminated, the time relative to high tide, tidal range, water temperature, prevailing wind direction and wind speed. “This is important not only from an ecological point of view,” continues Lauren; “but because it allows us to make predictions about where and when we might see manta rays aggregating throughout Seychelles and elsewhere around the world, and the kinds of behaviours that these animals might display at these sites”.

A reef manta ray being tagged at a cleaning station at D'Arros Island. Photo © Guy Stevens | Manta Trust

Their findings have shown that there is cause to create an MPA around D’Arros and St Joseph. Individuals were detected by the receivers year-round, with a peak in detections coinciding with the north-west monsoon. Reef mantas travelled widely within the Amirantes, with larger individuals travelling greater daily distances than smaller individuals and juveniles. On average, however, tagged manta rays were detected at D’Arros Island and St. Joseph Atoll on 64% of the days that they were tracked. “We definitely weren’t expecting such high levels of residency for so many of our mantas. We expected the juveniles to hang around for longer, but to see larger animals moving through the acoustic array in a similar manner and regardless of their sex was really interesting” marvels Lauren. Reef mantas were most likely to be detected during the day, at low wind speeds, and in balmy sea temperatures around 28˚C. They were more likely to be detected during a new moon, when the tidal range was at its highest, and on the slack of high tide.

Reef manta ray at D'Arros Island. Photo Ryan Daly | © Save Our Seas Foundation

For Lauren, it’s vital to tie the study’s findings to a wider conservation context, and she explains why the results are of particular importance to her: “I find the high residency rates that we reported for the tagged mantas at D’Arros to be really interesting, and particularly important from a conservation point of view. We aren’t just seeing juvenile mantas in this area; we see juveniles and adults, males and females, and they are all spending a large amount of time at D’Arros Island. Given that Seychelles is such a vast and remote area, the fact that we are seeing these animals spend so much time in this region is really important, not only for understanding the drivers of their behaviour, but for conserving this vulnerable species in Seychelles and for learning more about how they may be moving throughout the archipelago as a whole”.

Lauren Peel carries out a biopsy on a reef manta ray at D'Arros Island. Photo © Guy Stevens | Manta Trust

And what of the future for this winged-underwater species in the region? “Moving forward, I hope that this research stimulates interest in the manta rays in Seychelles at a community level so that we can get even more citizen scientists involved in our research and promoting manta conservation in the region.” Delving into the secret lives of these rays is a source of fascination to a scientist like Lauren. As curious as she is about the natural world, our current climate gives this kind of research a conservation imperative: “I also hope that our findings contribute knowledge to the development of scientifically-informed MPAs, particularly in the Amirantes and at D’Arros Island, but also at other locations throughout Seychelles where we know that mantas occur. A vital part of our research has been learning more about where these animals are aggregating, and the work we’ve completed at D’Arros to-date represents the first step in our efforts to better understand the importance of the different islands in Seychelles to these vulnerable animals. I really can’t thank the Save Our Seas Foundation and Manta Trust enough for their support of this research project and I look forward to continuing to develop the Seychelles Manta Ray Project with them”.

You can read the paper online here.

***Reference: Peel LR, Stevens GMW, Daly R, Keating Daly CA, Lea JSE, Clarke CR, Collin SP and Meekan MG. 2019. Movement and residency patterns of reef manta rays Mobula alfredi in the Amirante Islands, Seychelles. XX-xx.