The quest for the endangered bottlenose wedgefish

“Most of the time, they were still alive when being caught in the nets.”

“They are getting lesser now as compared to the past….”

These are some of the comments I often hear from fishers that we interviewed when investigating the fishery threats towards the bottlenose wedgefish (Rhynchobatus australiae) — a shark-like ray species that have been recently reclassified by the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species as “Critically Endangered” globally. This raises a huge concern as Malaysia is among the top shark and ray catching nations in the world, but the wedgefish is not legally protected in the country. This project was undertaken to better understand fishery threats and population connectivity in different regions of Malaysia using genetic analysis. Ultimately I hope our findings will help to conserve this species in Malaysia before it falls into the same fate as the iconic sawfish — which has not been observed in Malaysia since the 1980s!

A bottlenose wedgefish weighed about 43kg was unloaded from the fishing vessel’s cold storage and tossed onto the concrete floor. Photo © Amanda Leung

In December 2021, two undergraduate students from Universiti Malaya – Irsyad Pishal and Noavarat Virakun – and I began our journey exploring fishing villages and landing ports across Peninsula Malaysia in search of local fishers who would be willing to share their fishing stories and wedgefish encounters. Sharks and rays are locally known as “yu” and “pari” respectively. Interestingly, wedgefish are known locally as “yu kemejan”, reflecting the local perception of the species as being a type of shark due to their shark-like body shape.

A typical working day involves getting up early (for some days, 4 am in the morning to start the day!), packing our tools and datasheets, grabbing a light breakfast, and then driving to the field destinations.

Beautiful daytime scenery of the fishing village port in Sungai Besar, Selangor state, Malaysia. Photo © Amanda Leung

Part of my work relies on interviews with fishing communities. Fishers have a rich knowledge of the resources and the environment in which they work. Dr. Amy Then, senior lecturer at the Institute of Biological Sciences, Universiti Malaya, also my supervisor, and I developed and tested a questionnaire with a photographic guide for the interview surveys. Interviews as a tool are important to gather relevant information over a large geographic area within a feasible timeframe. Through interview surveys, we can tap into the fisher’s knowledge about fishing, wedgefish, cultural uses and the overall value of sharks and rays in Malaysia. This method could help us to better assess the threats facing and the current status of the species we are interested in.

Irsyad Pishal and I were conducting an interview with small-scale fishers in Pontian District, Johor. Photo © Lee Soon Loong

Most of the fishers we interviewed target other fish species. However, they would still retain ‘bycatch’ (a term used to include incidental catch of non-target species) of sharks and rays, including the wedgefish, for their meat and fin as additional sources of income — local wedgefish fins can, in fact, fetch up to 45.38 – 459.77 USD per kilo! Buyers are often more interested in the “white” fins of wedgefish as they are considered high-quality fins and are among the highest valued in the shark fin trade. Due to the highly prized fins, fishers will retain the wedgefish, especially the adult-sized animals.

These traditional fishers were so friendly and excited to share their fishy stories with the team in a wooden jetty house. Photo © Amanda Leung

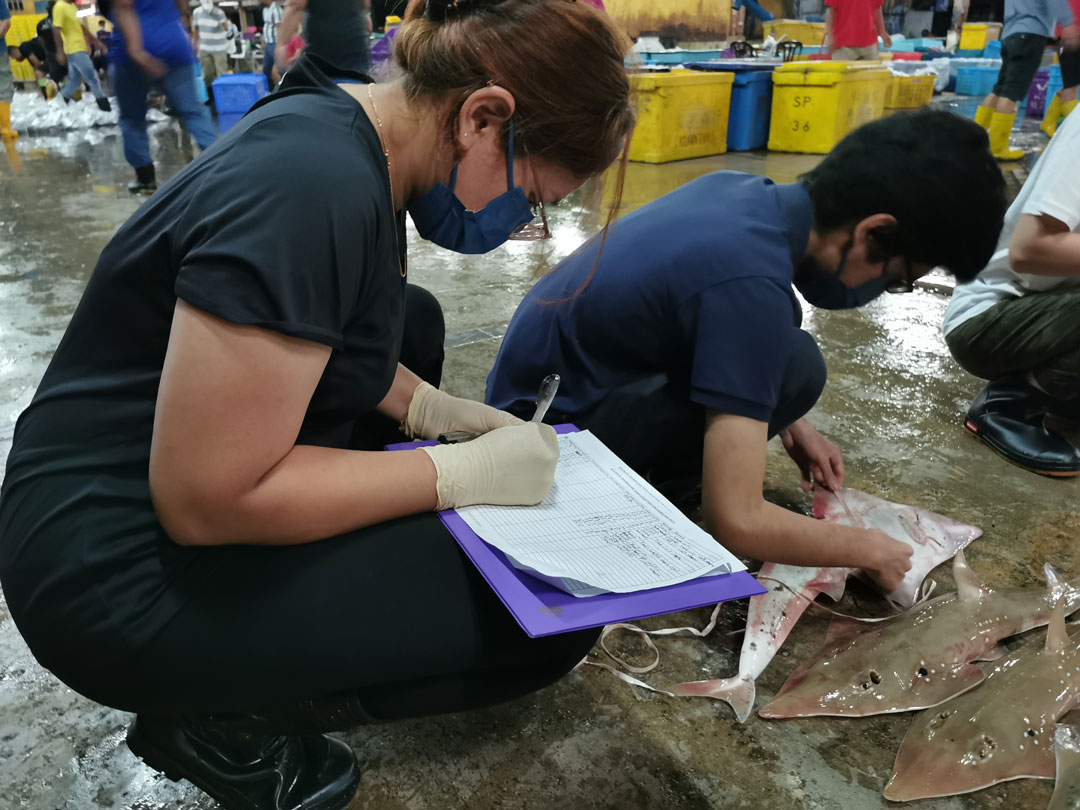

Besides searching for local fishers, we are also looking for individual wedgefish specimens at fish landing sites to collect tissue samples for genetic analysis. When we encounter whole specimens, big or small, we quickly obtain permission from the fishers to process the specimens before they are loaded onto a truck for sale elsewhere or are sold to buyers on the spot. We must work as quickly as possible, especially at busy and chaotic landing sites. The tissue samples are taken either from the edge of the pelvic fins or muscles near the pelvic fin where the small cuts are inconspicuous, before being stored in ethanol to preserve the DNA. Additionally, we would also record important biological information such as length and weight measurements, sex, and maturity status, and take photos of the specimens.

Noavarat Virakun and Irsyad Pisal were collecting biological information of the specimens. Photo © Amanda Leung

With the tissue samples on hand, we are ready for the next step — lab work! Stay tuned for a future blog post in which I will describe how I process these samples and why understanding the population connectivity is important to conserve the bottlenose wedgefish.