The Permitting Conundrum

What’s the hardest part about doing a regional study? It is probably not what you would think!

Managing sharks is difficult because they move back and forth across political boundaries. Therefore, regional studies are needed to understand population structure and to make cross-boundary recommendations for species conservation. Scalloped hammerheads are one such species with expansive ranges, but in the Caribbean data to understand this connectivity is lacking. Through our project, we sought to fill in some of these data gaps using genomic tools that only require fin clips from a relatively small sample of hammerheads across various locations. Ideally, 20 or more samples from a country are preferred, but even a few samples can be quite informative. The first step in this process was to develop partnerships and collaborations with shark researchers in other countries. Dr. Kingon and Dr. Portnoy already had some links and those people often led them to others. Dr. Kingon made additional connections by presenting the preliminary findings from this project at various conferences and workshops including Sharks International and the Gulf and Caribbean Fisheries Institute. With each presentation, she mentioned the need for increased regional sampling and made many integral connections in this manner. She further expanded this network by contacting shark scientists on ResearchGate and sending email requests on list serves. A wide range of new and old colleagues volunteered to help and were either willing to donate tissue samples they already possessed from scalloped hammerheads or they were willing to go out and collect them. This proved to be quite effective and in areas with high numbers of hammerheads and fishers catching them, our partners were able to make the collections without much effort, despite their critically endangered global status.

Surprisingly the hard part came with applying for permits to export the samples….

One of a few young-of-the-year scalloped hammerheads from Venezuela that they did sample for us but that they have been unable to get permits for to send it. Photo © Center for Shark Research (CIT)

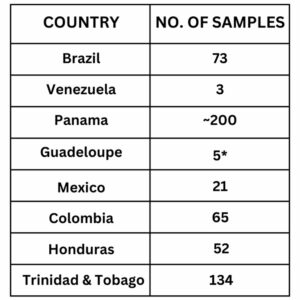

International regulations have been developed to stop or at least limit the trade of threatened species across borders. The Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES) enacted in 1975, is one of the primary governing conventions to limit the trade of listed species. It was initially developed to protect populations of animals like tigers and elephants that were being killed for their tusks or fur and then exported abroad as raw materials or made into highly sought-after products. Today CITES protects more than 40,000 species of animals and plants that are threatened with extinction. One of those species is the scalloped hammerhead and therefore to export any parts or pieces even for scientific study requires special CITES permits. In addition to CITES permits, most countries also require a national export permit and sometimes additional approved documentation. The process to apply for and get these permits is a lengthy and arduous task in most countries in the region. Once the permits are obtained from the country of export, the samples and paperwork often face scrutiny at the country of import, meaning that differences in procedures between countries may cause samples to be returned to the country of origin multiple times only to have to start the permitting process all over again. Below is a table of the countries where we have partners who have collected scalloped hammerhead samples for us, and the number of samples they have collected and still hold due to permitting setbacks (Table 1). Colleagues in Grenada, Barbados, St. Lucia, French Guiana and Haiti have also been on the look out for scalloped hammerheads but they did not encounter any over the period of this study. The permitting process in Costa Rica starts before collection of the samples and unfortunately was too cumbersome and restrictive to proceed further with partners there despite the species being present and fairly accessible in their waters.

Table 1. Countries where we have collaborators that have collected scalloped hammerhead samples for us, but they are still working on the permits to export them.

*These samples were recently successfully exported and imported!

The requirement for permits may be helping to restrict the international trade of threatened species to an extent, but it also can lead to an increase in illegal black markets where species are traded without going through the proper channels, either purposefully or unknowingly. Many customs officials across the Caribbean region are not aware of the CITES process or which species are CITES listed, making it easier for illegal trade to occur. The permitting process, however, is seriously restricting the sharing of scientific data that would help to better manage and conserve the species these regulations are meant to protect. A more streamlined and consistent permitting process across countries is needed, and better training on the CITES regulations for government officials, customs agents and businesses exporting animal and plant products. These measures would help increase regional data sharing for managing CITES species that cross borders, and also help to decrease the illegal trade of listed species. More education is especially imperative given the recent addition of many more shark and ray species to the CITES list.

A large fin sample that was seised from our colleagues in Venezuela, who weren’t allowed to sample without permits. Photo © Center for Shark Research (CIT)