The lost sharks and rays of Mauritania

No one knows the sea like a fisherman. This is true wherever you go, and it is the reason why scientists look to the fisher community for information where science does not have the answers. Their knowledge and stories are not only enticing but can transport you through time as their memories of the past collide with the mostly sombre realities of present-day challenges.

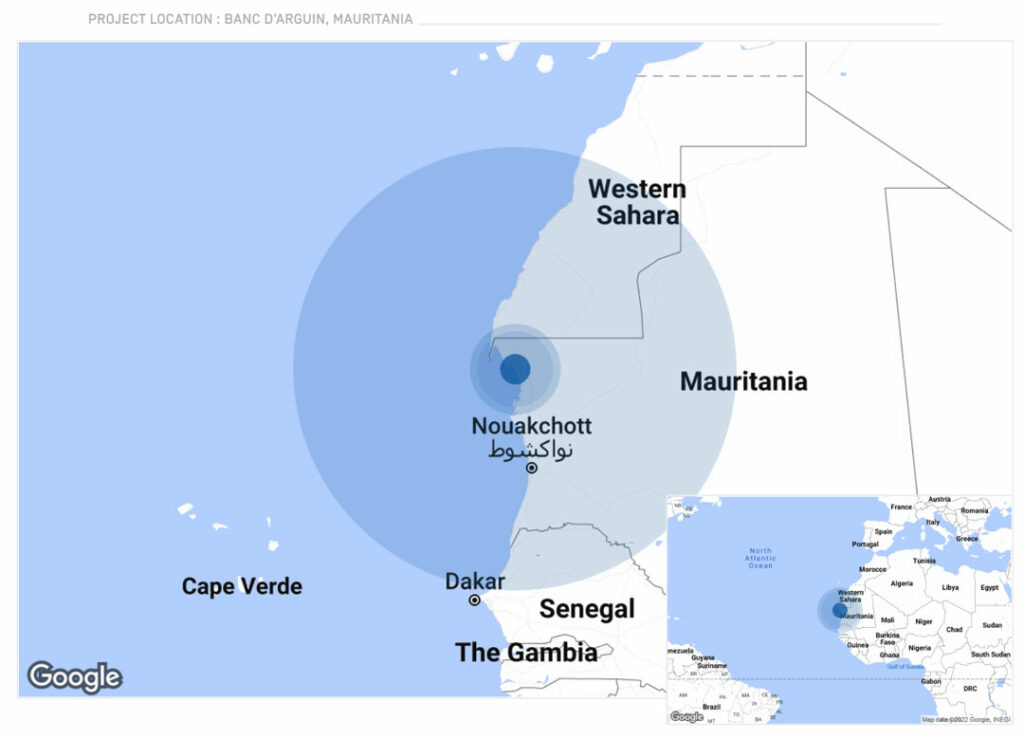

In Mauritania, the indigenous Imraguen fisher community has seen the marine landscape change in front of their eyes in the last few decades, with many of the larger shark and ray species extirpated from the waters of the Banc d’Arguin, West Africa’s largest MPA. In the words of one fisherman: ‘Once upon a time, all kinds of sharks existed here’. What I wanted to know is which ones.

While the Imraguen men are responsible for the fishing, it is the women who clean and prepare the fish. Photo © Carolina de la Hoz Schilling

My initial work in the Banc d’Arguin involved collecting water samples to extract shark and ray DNA to infer local species diversity from it. I found that some of the species I thought I would find, I didn’t, whilst some others that were not reported in the literature were found. So, I thought, who better to ask than the fishermen who have known the waters of the Banc d’Arguin since they were little?

One species that only the older generation of fishers remembers is ‘Jitt’ – or as we call it – the sawfish. Once apparently so abundant in certain areas of the Banc d’Arguin that you couldn’t hold your hands in the water without touching one, most fishers have not seen one since the late 1990s, when their emblematic saw-like rostra and fins were in high demand. All hope may not be lost, as a few fishermen reported last seeing a sawfish in 2017, yet one can only imagine what the waters may once have looked like with these beautiful animals swimming around.

Project location. Map © Google Maps

Another large species that is at the centre of many stories is the lemon shark, locally called ‘Tas Dakhna’, or the sand-coloured shark. Lemon sharks were said to be abundant a few decades ago and earned a great deal of respect from the fishermen, who used to fear them. Likewise, tiger sharks regularly roamed the waters of the Banc d’Arguin, according to the Imraguen. This was probably due to the large amounts of green turtles that like to feed on the abundant seagrass meadows in the bay, as many fishermen reported having found turtles inside tiger sharks’ stomachs. However, though the turtles remain, tiger sharks have not been sighted in many, many years.

Seagrass meadows in the Banc d’Arguin exposed during low tide are popular feeding grounds for many bird species. In the background is Iwik, the largest of nine Imraguen villages. Photo © Carolina de la Hoz Schilling

Not only do I mourn the loss of these species (and others), but it seems that so do the fishermen. When asked whether they thought sharks and rays were important, almost all had the same answer: ‘When there are no sharks, there is no fish’. Once upon a time, so they tell me, sharks served as guides to the local fishermen. When a large shark was spotted, fishermen would follow it to guide them to where the fish were, their true target, highlighting how fishermen perceive the presence of sharks as something positive, both for them and the marine ecosystem. Now, sharks and rays are only targeted locally because of the high demand and lucrative nature of their trade, with one fisherman accurately putting the current reality of not just the Imraguen but of most of the world’s coastal fishing communities into words: ‘So many people depend on me. Before, we used to have enough to eat, but it’s like a food web, if I don’t target certain species, then everyone who depends on me, also falls.’

The Imraguen fishermen still use traditional nets and non-motorized, wooden sailboats to fish the waters of the Banc d’Arguin, where they hold exclusive fishing rights. Photo © Carolina de la Hoz Schilling