Searching for silkies offshore

After an entire year of reading and writing at my desk, I finally stepped off the dock and onto the R/V Apalachee in St. Teresa, Florida. Along with the rest of the science crew from NOAA, FSU, and FIU, I loaded my belongings into the dark cabin’s cubbies and separated my clothes into two sets: one to fully immerse in fish and another to set aside for intermittent naps on a rocking bunk in between bouts of fishing. I can still smell the lingering aroma of Atlantic Mackerel on the former a few days after returning home.

The goal of our trip was to deploy satellite tags on three species of shark – silky sharks, night sharks, and oceanic whitetip sharks – in the northern Gulf of Mexico. Oceanic whitetips were once cited as “remarkably persistent” by researchers in the region and were probably one of the most abundant sharks on Earth as recently as the early 1900s. Now, oceanic whitetips and night sharks are challenging quarries because their populations have declined by over 80% in this area over the last three generations. Silkies are still one of the most abundant sharks on the planet, but their populations have also declined significantly in recent decades.

Adult silky sharks inspect bait far offshore. Photo © Brendan Talwar

We hoped to catch all three far offshore along the rim of DeSoto Canyon at the continental shelf edge, over 100 km south of the Florida-Alabama border. By dividing the crew into two teams, we managed to fish around the clock. One team set gear while the other slept, then both teams hauled gear, and then roles were reversed.

Unfortunately, we didn’t catch any oceanic whitetip sharks or taggable night sharks. But, on our second day of fishing during one particularly beautiful sunset, Dr Dean Grubbs (FSU), Blake Hamilton (recent MSc graduate from FSU), and Devanshi Kasana (FIU) were setting gear when a sharp tug on the line suggested a big catch. Given we were fishing baits at the surface alongside a Sargassum weedline, they hoped for the best and called on the rest of us to delay our nap. Silkies are lean and strong and don’t take kindly to being caught or worked up – the phrase “Hook me up another barrel!” (from Jaws) often comes to mind when they disappear below the surface with a polyball or two in tow.

Brian Moe (FSU), Dr. John Carlson (NOAA), and I swapped sleep clothes for fish clothes and encouraged our eyes to stay open while moving towards the back deck. When the fish broke the surface, we could tell it was a very large carcharhinid (family Carcharhinidae) – essentially, it had all the classic features that come to mind when you think of the word ‘shark’. But, from the pointed snout, small and distinctive first dorsal fin, and strong countershading illuminated by the boat’s searchlight, we had a good feeling that maybe we’d set our gear right on top of a silky shark. To work it up, half the team rigged up the sling and began raising the shark to the back deck while the rest of us prepared a satellite tag, tools, sample vials, and datasheets.

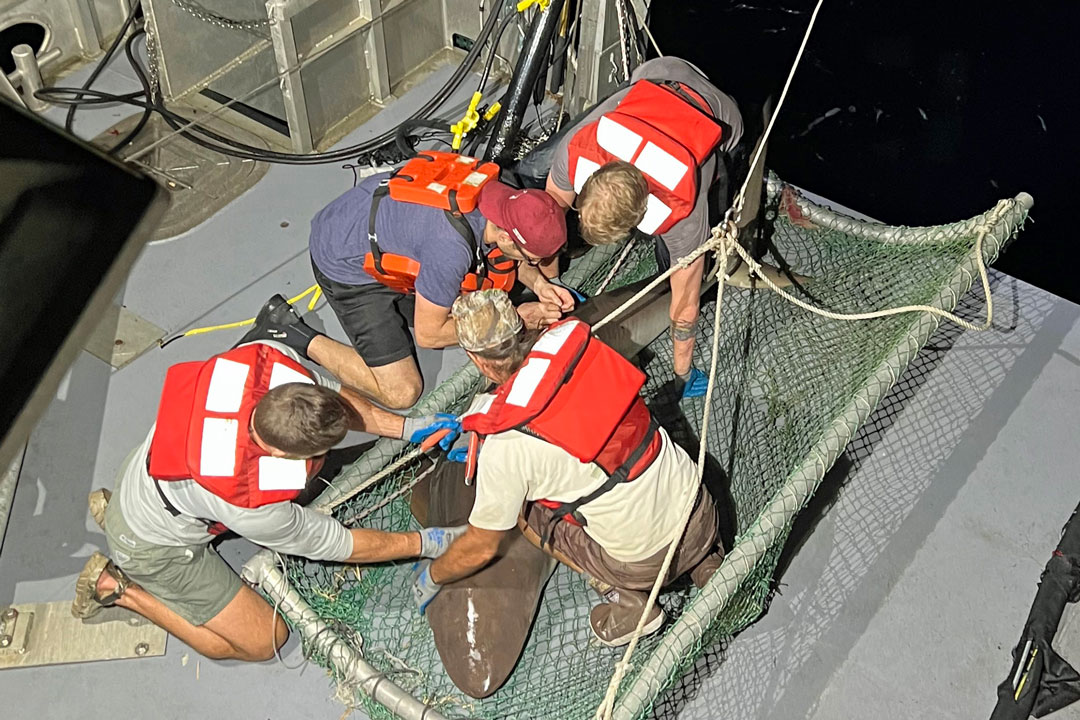

The research team attach a satellite tag to a large female silky shark. Photo © John Carlson

When the shark hit the deck, it put on a display of force rarely witnessed by the seasoned crew onboard. The adult female exhibited the same strength and attitude as the small juvenile silkies we caught last year off oil rigs near Louisiana, except this one was over 9 feet (281 cm) long. After a quick pop-up archival satellite tag (PSAT) deployment and standard workup, both of which were a bit more hands-off and rushed than normal due to the shark’s strength and irritability, we lowered the impatient shark into the water and watched her dash back into the dark Gulf waters. Whereas the small silky sharks that we tagged last year stayed in the northern Gulf of Mexico, we expect this large female to range widely across the region. If all goes well, we won’t hear from her tag until September when the tag is due to detach, float to the surface, and transmit data from wherever she ends up.

The research team celebrates a safe and productive trip after returning home. From top-left: Blake Hamilton, Captain Matt Edwards, (bottom left) John Carlson, Dean Grubbs, Brendan Talwar, Brian Moe, Devanshi Kasana.

By the time we hauled our last hook, we had achieved half of our goal for fieldwork this year – we deployed two satellite tags on large silky sharks far offshore in the northern Gulf of Mexico. We have two more tags that we hope to deploy later this summer. Then, data analysis and writing can begin.