Rescuing endangered mythical sea monsters in Mexico

Every time I leave the comfort of my home and head to the coast of Mexico to search for the smalltooth and largetooth sawfishes, my heart fills with excitement. Although the days of working on a small fishing boat under the hot sun, sometimes lashed by tropical rains and occasionally annoyed by mosquitoes and horse flies, are long and tough, they are some of the best days I can spend during the year.

Reef flats of Bahía de la Ascensión, Quintana Roo, where lemon and nurse sharks hang around. Photo © Ramón Bonfil

According to local fishers, the clear, shallow waters of Bahía de la Ascensión used to be a nursery ground for sawfishes some 50 years ago. Here an aerial view of Cay Culebra. Photo © Ramón Bonfil

I cherish the experience of passing entire days in mangrove forests, on the crystal-clear blue waters of coral reefs or on some of the largest rivers in the country, admiring birds, sea turtles, iguanas, howler monkeys and other wild fauna. Who would not swap the tedium of working in a city office for the pleasure of working in contact with nature? This is the best and most enjoyable de-stressing method I know – and it’s my job!

Our fishing gill net set in the mouth of a small stream in Los Petenes Biosphere Reserve, Campeche. We are always nearby and always watching over our fishing gear. Photo © Ramón Bonfil

A bird´s-eye view of our boat in the middle of a dense mangrove forest in Los Petenes Biosphere Reserve. Photo © Ramón Bonfil

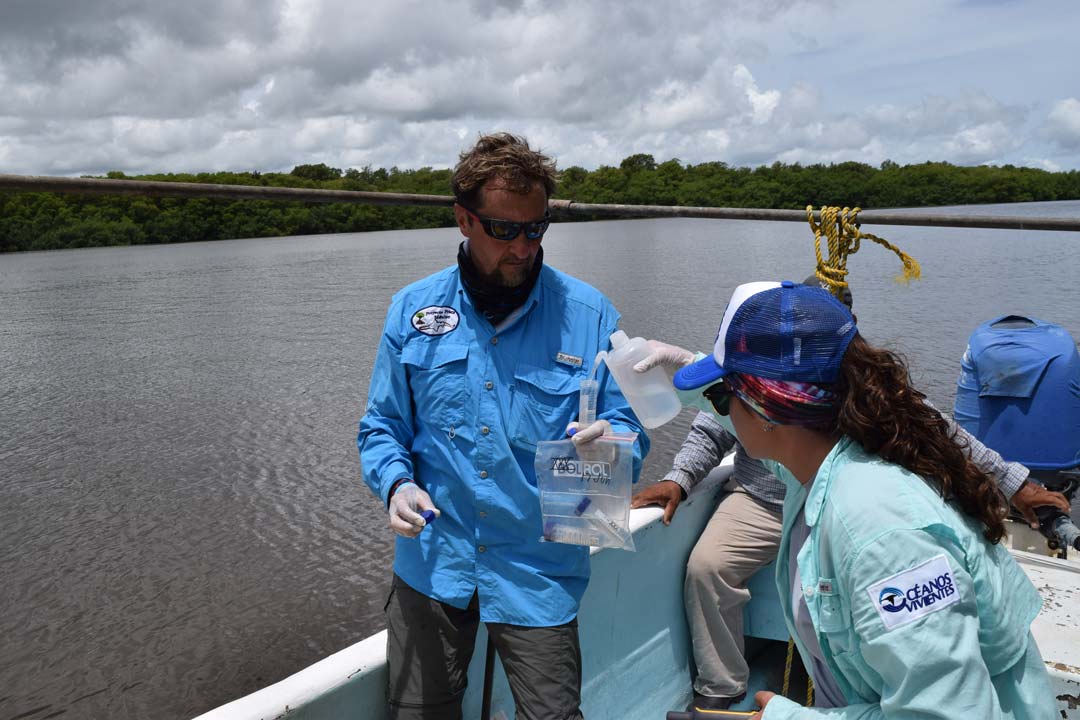

Water samples for eDNA are taken with all precautions to avoid contamination. © Ramón Bonfil

Once abundant along Mexico’s coast, both these sawfishes are now classified as Critically Endangered on the IUCN Red List. It is the search for them that fuels my drive to spend up to three weeks at a time, two to three times a year, roaming through bays, coastal lagoons, estuaries and rivers in tropical Mexico. Our research, beginning in 2015, has shown that both species were common all along the Atlantic coast of Mexico and that the largetooth sawfish also occurred along the Pacific coast south of the Gulf of California. Since the 1990s, though, few specimens have been seen. By-catch in coastal and inland fisheries and the degradation of the coastal zone are the main factors that have driven the populations of these two giant rays to the brink of extinction.

The clear waters of Chetumal Bay, Quintana Roo, were another habitat for sawfishes. The last known largetooth sawfish was caught here in 1979. This photograph shows a view of small islets where frigatebirds like to nest. Photo © Ramón Bonfil

These samples are then fixed in situ with ethanol to avoid DNA degradation. Here Triana Arguedas, a volunteer from Florida, helps the author to pour the ethanol into the sample. Photo © Ramón Bonfil

Since 2016 we have been personally searching for the last live sawfishes in Mexico, first with the aid of the Comisión Nacional de Áreas Protegidas and now with the generous support of the Save Our Seas Foundation and also the Marine Conservation Action Fund. Just last June I spent three weeks with a couple of volunteers surveying the entire Términos Lagoon and its tributaries, as well as Los Petenes Biosphere Reserve, both in the Mexican state of Campeche. Sawfishes used to be very abundant in those waters, although back in the 1950s a targeted fishery for them lasted only a few years. But nowadays just a handful of reports from local fishers seem to suggest that the number of sawfishes still in hiding somewhere is minimal.

Drones are helpful tools to locate sawfishes from the air and to document our work and sites. The author and Triana get the Phantom 4 ready for a flight. Photo © Ramón Bonfil

A drone ready for take-off from our ‘aircraft carrier’. The same technique is used for landing. Photo © Ramón Bonfil

Drones are flown at a maximum altitude of 65 feet (20 metres) for better viewing of subsurface aquatic animals. Here frigatebirds fly around our drone in Chetumal Bay. Photo © Ramón Bonfil

A typical working day involves getting up very early, having a hearty breakfast, preparing lunch and getting gasoline for the boat, and then loading up the gear. Then we sail up to 30 or 40 miles (50 to 65 kilometres) to our survey sites and begin selecting places to set our fishing gear, which we watch constantly for any sign of a catch. In areas with clear water, like the coastal bays of the Mexican Caribbean, we also do aerial transects using one or two drones to try to locate sawfishes from above. But our main search tool is a cutting-edge technique known as environmental DNA, or eDNA for short. All fishes constantly shed scales, mucus and gut cells into the environment, so we take water samples and then look for sawfish DNA in the lab. This is by far the best method to identify areas where sawfishes still live, since we do not need to catch or see them to know they live there. eDNA is so powerful that even at very low abundances it is possible to detect rare and endangered species.

Fishing nets are set perpendicular to shallow flats in mangrove forests and sometimes across stream mouths. Two volunteers, Michelle Carrillo from Mexico City and Triana Arguedas from Florida, are pulling back the net. Photo © Ramon Bonfil

Ramon and his team enjoy some magical moments in the middle of a stream completely covered by mangrove canopy. They aim to sample every possible sawfish habitat. Photo © Ramón Bonfil

Sometimes things do not go as predicted. The boat motor gave up on us this day in Los Petenes Biosphere Reserve and we had to return using an improvised sail. We were rescued that night at about 11 pm after drifting in the rain and dark for a few hours. Part of the adventure! Photo © Ramón Bonfil

So far we have not caught live sawfishes or seen them from the air, but we are hopeful that we’ll eventually do that. Once we manage to survey all the coastal areas where they existed (a task that will take three to five years), we will know which ones are the best to concentrate our fishing efforts in. I know that one day soon we will be able to find the sawfishes, tag them with satellite tags and begin working with the local communities and government authorities to ensure that they are cared for and survive. It is a long-term task, but one absolutely worth it!

Feeding yourself during an 8–10 hour day in a boat is not easy. We mostly resort to sandwiches, but after 15 days of this diet we appreciated some shrimp and sea snail ceviche. Photo © Ramon Bonfil

A happy and hard-working team on our recent field trip to Los Petenes Biosphere Reserve. Photo © Ramon Bonfil