Religion, a saving grace for Turama River sawfish and river sharks

Rostra and fins of a largetooth sawfish caught at the mouth of the Bamu River. Photo © Michael Grant | James Cook University

Papua New Guinea (PNG) is a country of rich indigenous traditions and cultural values. Before western settlers arrived at its shores, many regions held intimate spiritual connections with the cycles and aesthetics of the natural world around them. From the crocodile clans of the Sepik River to the birds of paradise whose beauty was captured by David Attenborough in 1957, animals have played an integral role in spiritual and physical well-being of individuals throughout PNG.

A recently constructed church building on the Bamu River. Photo © Michael Grant | James Cook University

Over the late 19th century, a new wave of religious beliefs swept the nation. Today 95.6% per cent of PNG’s indigenous population identify as a denomination of Christianity. Within this same period, PNG has also been exposed to Asian cultures with Chinese and Indo-Malay owned shops and hotels present in most regional towns. Authentic traditions and cultural values still exist throughout PNG, although for many regions they are often reserved for major life events such as births, initiation to maturity, marriage, and death. Day-to-day cultural values are now increasingly centred around the Christian church.

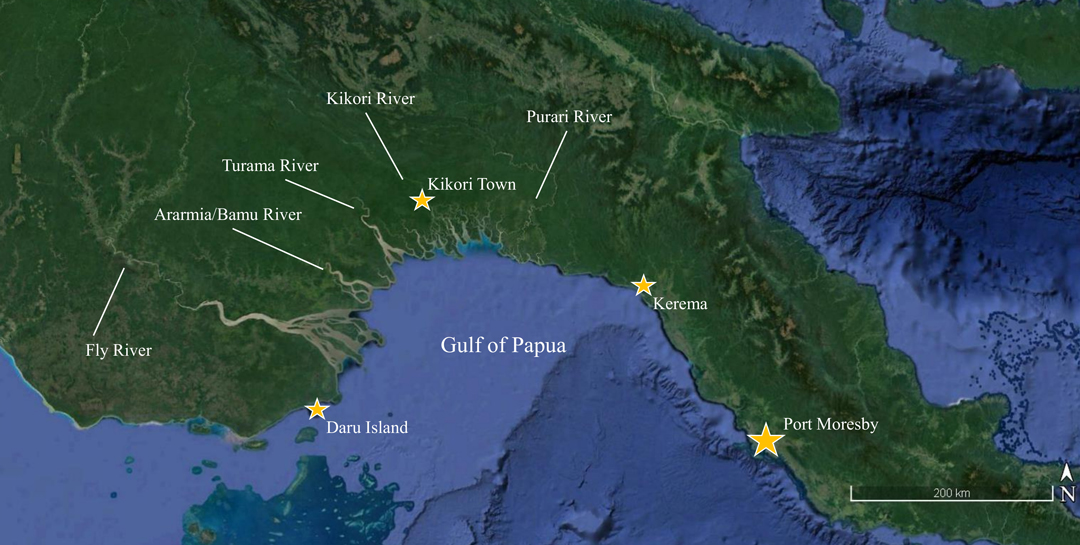

Gulf of Papua and major river systems. Base image © NASA | Terra Metrics | Google Earth

The Gulf of Papua is emerging as a global stronghold for many endangered euryhaline and estuarine shark and ray species. All four Indo-Pacific sawfish species (narrow sawfish Anoxypristis cuspidata, dwarf sawfish Pristis clavata, green sawfish Pristis zijsron, and largetooth sawfish Pristis pristis and two species of river shark (northern river shark Glyphis garricki and the speartooth shark Glyphis glyphis can be found in the Gulf of Papua. The Gulf of Papua has many large river systems draining into the Gulf which provide ideal shallow, turbid, and low salinity conditions for these species. Furthermore, population density is very low throughout the Gulf of Papua and its rivers, as dense rain forest and expansive flood plains preclude the development of roads and transport infrastructure. For this reason, communities in the region are small and highly dispersed, generally living off the natural resources available.

Dried rostrum from a juvenile Critically Endangered largetooth sawfish, Turama River. Photo © Michael Grant | James Cook University

Dorsal fin of an Endangered river shark caught at the mouth of the Bamu River. Photo © Michael Grant | James Cook University

In recent decades however, influences from western and Asian cultures has led to an increase in natural resource exploitation throughout PNG. This has been dominated by mining, logging and fisheries sectors. For small-scale fisheries, items including sea cucumber, fish swim bladder (also known as fish maw), and shark fin are routinely traded across the West Papua border into Asia. Demand for these products has resulted in a shift from traditional fishing gear (e.g. traps, spears, and wooden paddle canoes) to modern synthetic nylon and braided fishing line and gillnets, coupled with fibreglass boats and outboard motors. The swim bladder carries the highest value for small-scale fishers. In South-East Asian medicine, the fibres of dried swim bladder are used for bio-sutures, a cheap alternative to expensive synthetic sutures. Swim bladders from barramundi and jewfish, both common in estuaries, are preferred as they are large and well suited for the use. Sharks and shark-like-rays (i.e. sawfish, wedgefish and guitarfish) are often caught in fishing gear targeting these fish species, and consequently, they are often finned and consumed or sold in local markets for additional income. While the unregistered sale of swim bladder and shark fin to international buyers is not legal in PNG, small scale fishing targeting these products are commonplace throughout the dispersed communities in the Gulf of Papua.

A fishermen in a traditional canoe, south of Kerema (Left). Modernised nylon gill nets loaded in a fiberglass boat ready to be deployed at the mouth of the Kikori River by local fishermen (Right). Photos © Michael Grant | James Cook University

Collectively, these small-scale fisheries targeting swim bladder and shark fin are presently the biggest conservation concern for sawfish and river shark species living in the estuarine environments throughout the Gulf of Papua. With increasing access to more sophisticated fishing gear, boats, and fuel, the problem is likely to become more severe.

In the Turama River, Christianity offers some respite for sawfish and river sharks. Most communities on the Turama River are Seventh Day Adventist. Followers of the Seventh Day Adventist Church cannot eat non-scaly fish as part of their practising obligations. Furthermore, Turama River sits right in the north western corner of the Gulf of Papua, making it costly for locals to travel to Daru Island, Kikori Town, or Kerema to sell fish products (image 2). For this reason, sawfish and river sharks have little value to local communities and they are rarely retained by fishermen thus, providing a safe haven for these endangered species.