Pass the gloves: chasing narrow sawfish eDNA

As a field biologist who has worked with sharks and rays all over the world I’ve had some amazing experiences, including wrangling 15 foot sawfish in the Everglades, snorkelling with whale sharks off the Yucatan and tagging reef sharks on the Great Barrier Reef. So I can tell you with some authority that field work for environmental DNA (eDNA) research is about the least fulfilling I have ever done.

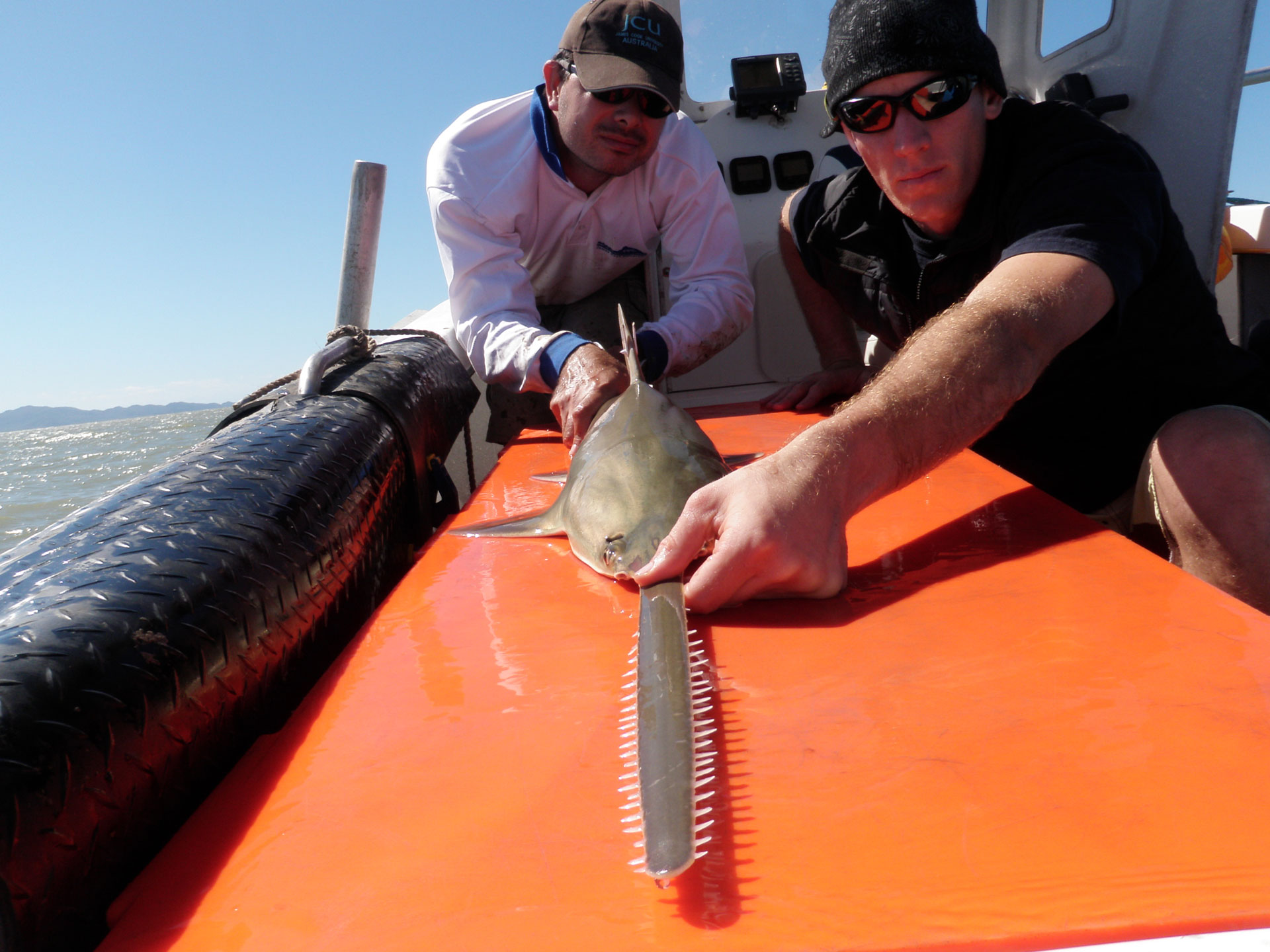

Narrow sawfish are one of five species of sawfish known globally. This species is the only one that regularly occurs along the east coast of Queensland. This one was tagged and released by researchers off Townsville by researchers. Photo © Colin Simpfendorfer | James Cook University

Take our last field trip as an example. We had heard from local fishers that large narrow sawfish (Anoxyprists cuspidata) were being caught along the beaches just to the north of Townsville where we are based. This was a great opportunity to test our newly developed probes for identifying this species. So we prepped the gear (mostly involving bleach and UV irradiation) packed the truck and headed up the highway early the next morning.

First stop was Toomulla Beach. We pulled up on the side of the road above a small sandy beach. I grabbed the sampling equipment – a pole from a pool leaf scoop, bucket and one litre bottle. Not your standard issue for a shark biologist. Meanwhile Madie Cooper, the PhD student working on the project, busied herself prepping our mobile laboratory on the tailgate of the truck. This mobile lab consists of a small pump and associated equipment for filtering eDNA samples in the field. We are sending these mobile laboratories all over the world so that our collaborators can collect samples in their country to help us understand the current global distribution of sawfish.

Water sampling at Toomulla Beach for sawfish eDNA on a beautiful spring morning. Photo © Melissa Joyce | James Cook University.

As I walk down the beach I pause briefly to survey the water. It is a perfect morning. No wind and just small waves ruffling the surface. More importantly, I check for signs of crocodiles. This is an important part of our safety procedures since we work in areas where large crocodiles are frequently encountered. With it all clear I wade into the warm water and start scooping up some water. Five litres was Madie’s request. I get six just to be on the safe side. I trudge back up the hill to the truck to deliver the samples.

Madie has the mobile lab all set to go. “Gloves”, she reminds me. I slide on a new pair of disposable gloves, not the easiest task with damp hands from collecting water. One of the things I’ve learned about eDNA fieldwork is that there are a thousand ways that your samples can be contaminated. Making sure we have protocols that reduce the risk of contamination is a key to success of this type of work. Gloves, and lots of bleach, are two important parts of that protocol. With my gloves on I set about helping Madie process the water samples.

PhD student Madalyn Cooper filtering water in her “mobile” lab on the tailgate of a truck. Photo © Colin Simpfendorfer | James Cook University

The water is filtered through five 10 micron filters that trap any DNA fragments in the water, and of course any other particles as well. Sometime this can make for slow going if the filters get clogged. But today the clear water from the beach filters fairly quickly and we soon have the filters stored in preservative buffer for transport back to the laboratory where they will be processed. Then we pack up the mobile lab and set off for the next location; a creek just a kilometre to the south. We repeat this process several times, collecting samples at five locations as we travel south back towards Townsville.

Small estuaries, along with sandy beaches, are sampled using eDNA techniques to detect the presence of sawfishes. Photo © Colin Simpfendorfer | James Cook University

Just after lunch we are done. All we have to show for our efforts is a small box of vials with the preserved filters in them. We will have to wait weeks now for the results to come back. No idea if our efforts will be rewarded by positive results for the one species of sawfish that remains on this part of the Queensland coast. That is what makes eDNA sampling so unfulfilling. You don’t get to see the amazing animals you are studying, and you have to wait weeks to find out if you were successful.

But in the end, the results that this project generates will be reward enough for a lack of fulfilment during field trips. We will know where in the world sawfish populations still exist, helping focus conservation efforts in the places where they will be most successful.