Mid-Atlantic devil rays reloaded

As the olive-brownish shape of a Chilean devil ray emerges from the depths next to our boat, the familiar excitement I get when seeing my study animals – whether great white sharks or devil rays – invades me and my heart starts to rush…

I am back at the Archipelago of St Paul and St Peter (ASPSP) in the middle of the equatorial Atlantic Ocean to continue our study on the conservation ecology of devil rays. This time I enjoy the company of Sibele Mendonça and Bruno Macena, two doctoral students at the Universidade Federal Rural de Pernambuco (UFRPE) in Recife, Brazil, where I spent a year as a visiting professor in 2013–2014. It was then that I joined the efforts initiated at UFRPE by my friend and colleague Dr Fabio Hazin to understand the life history and threats faced by devil rays in this part of the world. Since then we have formed a partnership that includes the project being carried out at the ASPSP as well as another that I will begin with Oceános Vivientes A.C. on the Yucatan Peninsula of my native Mexico as soon as I return from this adventure. Our partnership, funded by the Save Our Seas Foundation (SOSF), Marine Conservation Alliance Foundation (MCAF), the Brazilian National Council for Scientific and Technological Development (CNPq), the Inter-ministerial Secretariat for Marine Resources (SECIRM), UFRPE and Oceános Vivientes A.C., involves studies in Brazil and Mexico, and a global collaboration with the Manta Trust. All these studies are aimed at a better understanding of the biology and ecology of devil rays, as well as the threats they face, in order to design improved conservation measures for them.

Aerial view of the ASPSP showing the research station/lab/living quarters, and the lighthouse. © Photo by Ramón Bonfil

This time, with the support of the SOSF, we are here to deploy three pop-up archival (PAT) tags on Chilean devil rays Mobula tarapacana so that we can learn more about the species’ migrations, depth and temperature preferences, and the threats the rays may face if they travel to areas where they are not protected. (Brazil, along with Indonesia, Mexico and a few other countries, has passed legislation making it illegal to fish for this magnificent ‘flying’ marine animal.)

Chilean devil rays Mobula tarapacana often travel in groups of several individuals. © Photo by Sibele Mendonça

Last year we deployed an MK10 PAT tag on two female Chilean devil rays, with encouraging results. We followed Victoria’s progress for 120 days as she travelled towards the west coast of Africa, and tracked Maya for 90 days as she hung around the ASPSP. This time we are more ambitious and plan to tag three rays and track them for an entire year – that is, if the tags stay attached for that long. When we are dealing with such formidable swimmers, it is difficult to guarantee that the darts we use to attach the tags will remain in their bodies for a long time. Then there is the problem of depth. A recent study in the Azores has shown that Chilean devil rays can dive to almost 2,000 metres, but our tags can only sustain the pressure down to 1,800 metres. So if one of our tagged rays goes deeper than that, the tag will detach automatically or be destroyed.

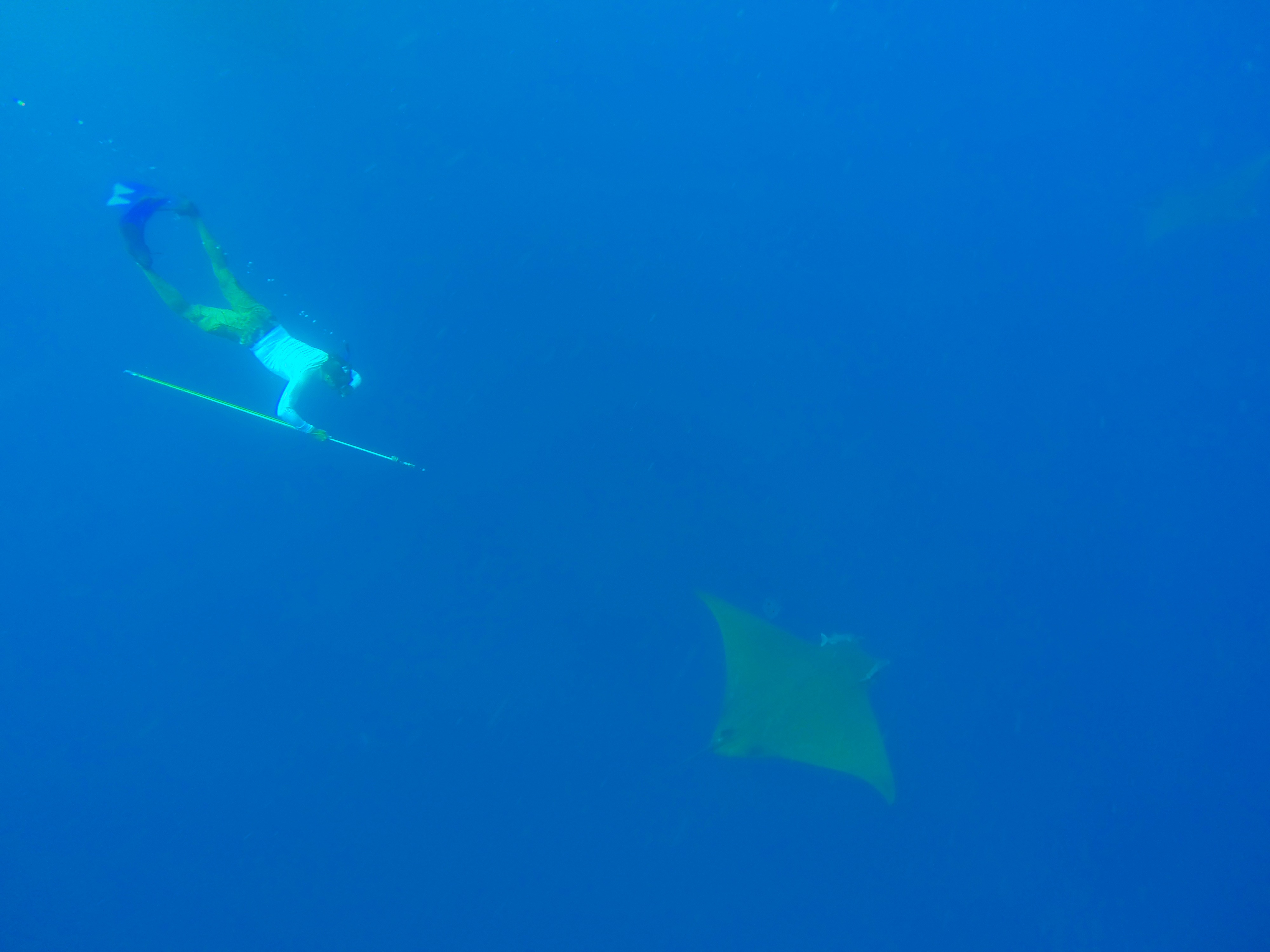

Schools of king fish are plentiful in the waters around the archipelago Here Dr Ramón Bonfil dives in the blue waters in search for Chilean devil rays. © Photo by Sibele Mendonça

But our first challenge is to find the rays and tag them. This might sound easy, but working with wild animals is always unpredictable. Sibele has been here for four weeks already this year and she has seen only a handful of devil rays so far. However, I reassure her that since I am now here – after a lot of preparation, hard work and travel – the devil rays ‘know’ it and they will show up! And it seems that The Seven are on my side, since on the very first day I spend on the boat looking for them, a group of five rays shows up within 30 minutes of me beginning to scour the ocean!

Chilean devil rays, Mobula tarapacana are gentle and curious creatures that often come extremely close to us while we are free diving. © Photo by Sibele Mendonça

Unfortunately, we are not yet prepared for tagging. Getting all the equipment ready is difficult, especially when our team works from two different countries and via e-mail for all expedition preparations. For the first two days after I arrived I had to stay on land (actually on the jagged rocks we call home at the ASPSP), testing our satellite tags and programming them. Bruno and Sibele, meanwhile, were working on another UFRPE project here. They were long-lining for sharks to tag them with acoustic tags and spent a whole night working in the fishing boat without sleep. So now I am alone here during the day and our tagging pole has not been furnished yet. All I can do is try to obtain small tissue samples from some of the rays.

As I prepare to enter the water, the devil ray that is close to the boat disappears. Chilean devil rays tend to swim slowly and gently, sometimes near the surface, and I know that they usually circle back or hang around the area. So I enter the water and begin to search around the deep blue void. The fishermen who crew the boat and serve as our support team tell me that the rays are now about 50 metres away. I soon see them and begin to try to predict their path. My first free-dive meets with a problem, as my new GoPro camera, bought with the support of the SOSF and fastened to my forehead with a head strap, is pushed back from my head and threatens to go for an eternal deep dive on its own. I manage to fasten it more securely and head towards the group of rays, which is now circling back towards me. Chilean devil rays are curious and often like to hang around divers and give them a good look. This is very different behaviour from that of their smaller cousins, bentfin devil rays Mobula thurstoni, which also live at the ASPSP but tend to swim faster and deeper and never allow us to get close to them.

I dive in, hoping to get the first tissue sample and some awesome video of my feat. As I approach a male and position myself behind and above him, he slows down a bit and I take careful aim and shoot. A perfect shot and I get my first small cylinder of tissue as the ray dashes away, scared by the prick (don’t worry, it doesn’t bleed; to us it would feel like a small jab). As usual, within 15 seconds he is back and he and his group circle around me for a couple more minutes before disappearing into the blue.

My smile of satisfaction as I return to the boat is huge, but I get a quick reminder that things often go wrong in the field. My new camera is not cooperating; by mistake I set it to take photographs, so I only get a blurry picture of the ray from afar instead of a detailed video of the whole encounter and sampling process.

Dr Ramón Bonfil dives in to take a biopsy from a Chilean devil ray Mobula tarapacana. © Photo by Sibele Mendonça

But The Seven are with us, and things get even better on the next day we spend searching for devil rays. We have to wait two more days for this, as the weather is rough the following day and the one after that we rest at the station because we have been long-lining for sharks all night. This time Sibele and Bruno are with me and our tagging poles and tags are ready… And this time again, a group of rays – this time four – shows up next to us within a few minutes of our arrival. Sibele and I get into the water and the first Chilean devil ray that comes to check me out is my target. However, they are swimming quite deep, at about six metres down, and my lungs and physical condition are not what they were 20 years ago. I dive in towards the first ray of the group, a female, but she outswims me. I keep going, however, and soon the second ray, also a female, is just under me. With a few more gentle kicks, I close in on her. She slows down and I zoom in to her left side, about 20 centimetres from her tail, and let go the shot with my Hawaiian sling. Done! Anita, our first female Chilean devil ray of this trip, is proudly carrying a mini-PAT tag that should stay with her for an entire year and give us invaluable information about her horizontal and vertical movements. To make things even better, while I was busy with the tagging, Bruno has taken another tissue sample, this time from a female. What a great day!

Two Chilean devil rays Mobula tarapacana checking us out at the surface The ray on the right was tagged just seconds before; the small miniPAT tag can be seen on its rear left dorsal side. © Photo by Sibele Mendonça

Every day, after spending most of the daylight hours in the boat patiently searching for devil rays or interacting with them, we still have lots of work waiting for us when we return to the station. Cataloguing the tissue samples and putting them in alcohol, writing logs of what happened each day, cleaning equipment and preparing it for the next day, and downloading all the photos and video we have taken (Sibele has the second GoPro camera we bought with SOSF funding). This last task is the most exciting one because we get to see how informative our photographs and video are. They help us to document the sex of the rays, the exact position of the tag or tissue sample, and hopefully details about the underside of the rays, which often have dark markings that can help us identify individuals. Our expeditions are no vacation in paradise; it is hard and constant work, but very rewarding. The scenery is awesome and the brown boobies and brown noddies are always entertaining, hanging around our veranda and boardwalk and often making us the target of their droppings!

Brown boobies are the most common and amusing animals living on the jagged rocks that make the ASPSP. © Photo by Ramón Bonfil

The following day we don’t get to see the rays, despite spending several hours looking for them. But when we get back to the station we do something I have been looking forward to and dreading at the same time. I brought a drone that I got with help from the MCAF. I hope to use it to document our research and find the rays more easily, but I am anxious to see how the birds on the island will react to it, and how it will perform in the constant winds we experience out here in the middle of the Atlantic. With the help of Bruno and Sibele, I fly the drone in the ASPSP for the first time. All goes well, although the birds are obviously startled. Suddenly the whole sky is full of boobies and noddies flying around and approaching the drone, alarmed by what they see as a potential threat to their nests. Although some daring birds get close to the machine, none actually attack it. It would have been a total disaster had they done so, since both bird and drone would have been damaged. Instead, I get some fantastic video and photographs of our small rocky outcrop from above!

As the days go by, we make great progress with our objectives for this field work expedition. Only two days after we tagged Anita, Bruno tags another two Chilean devil rays, a male and a female, on the same day and from the same group. I was supposed to tag one and Bruno the other, but the rubber band on my Hawaiian sling detached just as I was preparing to shoot the tag. No problem for Bruno, who tagged a male, Arturo, as soon as he entered the water. He usually tags devil rays using a simple pole without a rubber band, so when I tell him about my equipment malfunction he takes my pole and within a few minutes he tags a second ray, this time a female, Genie (in memory of the late ‘Shark Lady’, Genie Clark). We have achieved all our tagging goals – the three mini-PAT tags we brought with us have been deployed!

Bruno Macena deploys a miniPAT tag on a female Chilean devil ray Mobula tarapacana. © Photo by Sibele Mendonça

Now we just have to wait patiently for a year, hoping that the tags do report the data they have collected at the end of the 365 days they were programmed for. However, we know that a number of things can go wrong. Sometimes tags detach earlier than programmed, as explained above, and sometimes we just never hear from them; they disappear and we never know what went wrong. The date for them to detach, float to the surface and start transmitting their data comes and goes and we hear nothing from them. This can be because of tag failure, because the tag was damaged or destroyed, or because it ended up in a place it cannot transmit from (trapped underwater, in a dry place on land or perhaps in the belly of a predator).

The research team after tagging the first Chilean devil rays of the expedition (from right to left, Sibele Mendonça, Bruno Macena and Ramón Bonfil). © Photo by Ramón Bonfil

The rest of the expedition is a pleasure. We obtain several valuable tissue samples from the devil rays without the pressure of having to deploy the tags. We also have an unbelievable encounter with a group of more than 30 Chilean devil rays! We have never witnessed such a large group before and although they stay at a depth of more than 10 metres – too deep for us to reach them – we enjoy watching and photographing them. Then, on the very last day of the expedition, we finally manage to shoot some video and photographs of both Chilean and bentfin devil rays with the drone!

Researchers Sibele Mendonça and Bruno Macena interacting with a group of four Chilean devil rays Mobula tarapacana. © Photo by Ramón Bonfil

As we pack and prepare to return to the mainland, I realise this place offers unique and exceptional opportunities for research. A number of important questions about the biology and ecology of the devil rays have popped into my mind during my stay and I hope to return soon to this paradise to continue studying these fantastic and poorly known animals. It will all depend on how lucky I am in obtaining further funding…