Like finding a Pacific spiny dogfish in a haystack

My line of work poses a unique problem. I like to study species that are threatened or rare, which (shocker!) means that they can be very hard to find. That is an unfortunate reality of working with Pacific spiny dogfish. The dogfish is a small, historically common predator in the Northeast Pacific. However, dogfish have been fished heavily for over half a century, and even today, their movements overlap with many valuable fisheries. For example, where I work in Oregon, we get reports of massive hauls of dogfish caught on accident by local fishermen. This bycatch is certainly problematic for the fishermen because it displaces their desired catch. Plus, as the name “spiny dogfish” suggests, handling these sharks can be a prickly endeavor (nobody wants to deal with the spines found at the base of the dorsal fin). Even worse, capture by fisheries is likely contributing to substantial declines that have been reported in our local stock (or population) of dogfish, a subset of the species that ranges from the coasts of Washington and Oregon to southern California. Just how bad is this problem? That’s what our team is trying to find out.

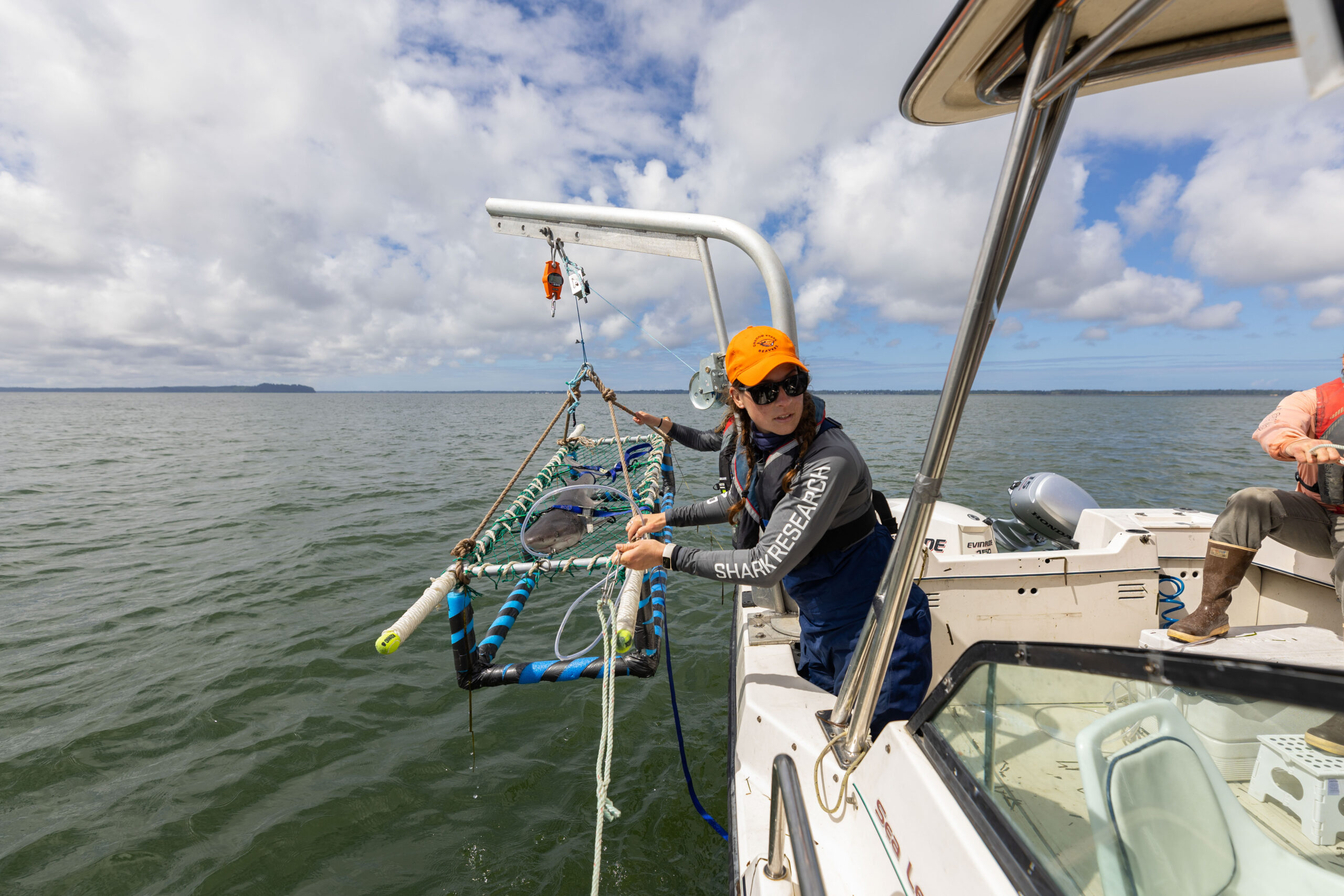

Dr. McInturf in the field along the coast of the US Pacific Northwest. The Big Fish Lab captures many species here in addition to Pacific spiny dogfish, including sevengill sharks (pictured here). Photo © OSU Media

As researchers at Oregon State University’s Big Fish Lab, we were first approached by the stock assessment team at NOAA (responsible for analyzing dogfish population trends) and the Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife (ODFW) in 2023 to help learn more about the status of the Pacific coast stock of dogfish. Specifically, the stock assessment, which is a tool that is used to help make management decisions, is traditionally based on NOAA surveys, in which dogfish are caught and counted. However, NOAA surveys are restricted to specific months and locations, and our colleagues were unsure if this effort adequately captured dogfish numbers. Our team was asked to provide tag data to better determine the accuracy of the surveys. Tags, which are devices that can track movement and/or behavior, help overcome several of the limitations of surveys; they can track year-round regardless of location, helping us learn more about where animals go beyond our ability to observe or capture them.

In 2024, we began our tagging efforts in earnest. As part of the larger collaboration, we are deploying satellite tags (which transmit information such as location, depth, and temperature) on adult dogfish. However, dogfish are not very big (just over a meter long), and satellite tags are too large for smaller individuals, like juveniles. Yet capture records indicate that many juveniles are caught in fisheries accidentally, which means this is an age group we want to examine. Thus, with the help of the SOSF, we aim to deploy acoustic tags on juvenile dogfish. These tags are a bit smaller and send out an underwater sound signal that can be detected by listening devices (“receivers”) we have moored along the coast in Oregon, Washington, and California.

A Pacific spiny dogfish outfitted with a satellite tag during a research survey during fall, 2024, as part of a larger project examining the movement and distribution of this species in the Northeast Pacific Ocean. Photo © Alexandra McInturf

I quickly realized, however, that I had fallen back into my old trap. Finding sharks from a declining population is hard. We scoured every part of the northern California, Oregon, and southern Washington coasts, sending team members out on NOAA research surveys, targeted fishing on our own, and seeking out fishermen who might host us on their vessels. So far, we have successfully deployed 6 satellite tags and 5 acoustic tags. With winter coming, we have reasons to be optimistic: those are the months when most dogfish are reported by fishing vessels. However, it’s always hard to know what the weather will bring at this time of year. Stay tuned for more updates!