Keeping watch over Antarctica’s penguins

Dr Tom Hart. Photo © Jeff Mauritzen.

My name is Tom Hart, and I’m a Penguinologist leading the Polar Ecology and Conservation research group at Oxford University. The Save Our Seas Foundation has helped us take advantage of a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity for a natural experiment. The effective removal of humans from the Antarctic Peninsula means understanding and disentangling the other threats penguins.

I’m currently on board the NG Resolution, an expedition ship that tours the Antarctic Peninsula and the Scotia Sea. I’m trying to get around a network of over 100 penguin colonies with timelapse cameras on them.

Penguin Watch camera overlooking a gentoo colony at Neko Harbour. Photo © Ignacio Nacho Juarez.

Over the last decade, I have successfully designed this novel technique that combines remote time-lapse camera technology with a citizen-science-powered data processing platform as a way of efficiently monitoring penguin populations in a hard-to-reach environment. I was fortunate to keep this network going last year via a private expedition with the Save our Seas Foundation. I’m now trying to recover more data showing the effects on penguins of a year without people.

Gentoo penguin and chicks at Madder Cliffs. Photo © Fiona M Jones.

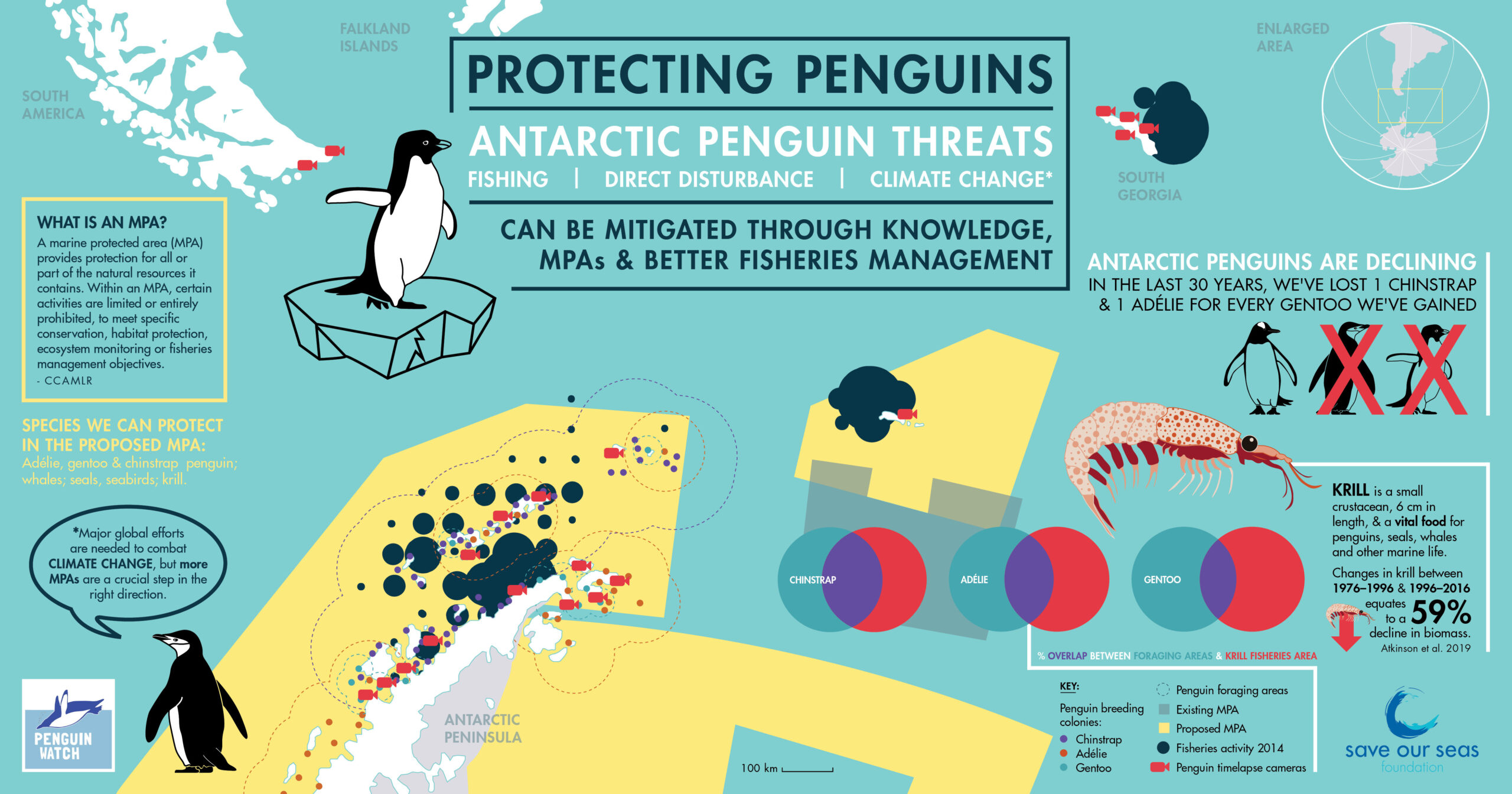

The Antarctic Peninsula is changing rapidly, and penguins are responding. We already see the loss of Adelie and Chinstrap penguins and an increase in Gentoo Penguins. Very roughly, we are losing one Chinstrap and one Adelie for every Gentoo we gain. In the context of change, there are winners and losers. The potential causes of these changes are climate change, fishing, tourism, whale recovery and disturbance through national programmes (the national bases around Antarctica). But the problem is that so many of these threats overlap on the Antarctic Peninsula, so it’s tough to disentangle them. For example, fishing vessels can reach new areas for longer as sea ice declines, so it is hard to attribute changes in penguins to climate change or fishing. It could be either or both.

Penguinologists at work servicing a chinstrap camera on Gaston island. Photo © Penguin Watch.

Penguin Watch has been going for 13 years now – the idea is that by placing timelapse cameras overlooking penguin colonies, we can collect such detailed observations almost hourly that would otherwise require a scientific base and all of the infrastructure and disturbance that entails. This network of cameras has recorded the change in penguin breeding for over a decade and is documenting dramatic shifts in the timing and success of breeding associated with warming temperatures and possibly krill fishing. The intent of the network was always to investigate the effects of climate change and fishing – that was why we put it in place. Still, one of the natural strengths of having a monitoring network in place is the ability to record unexpected events. One of these unexpected events has been the COVID-19 pandemic, which for a year and a half stopped all tourism in Antarctica and disrupted national programmes and fishing. As a result, we’re in a great natural experiment that can help us understand the relative influence of climate change and fishing on the changes we see in penguins. I hope there is an upside from COVID-19 that might help provide the evidence we need to protect penguins.

Disentangling the threats faced by Antarctica's penguin populations by looking at where colonies and feeding grounds overlap with possible threats. Artwork by Nicola Poulos | © Save Our Seas Foundation