How to Keep a Sawfish Alive

Part 1: Getting to know you…

When I first set eyes on a sawfish, nearly 60 years ago, it was swimming around in the Durban Aquarium, South Africa. It may well have been sharing the aquarium with several bull sharks. Locally known as Zambezi sharks, they had been blamed for a spate of attacks off Durban’s beaches, and were therefore of considerable interest to the civic authorities and biologists alike.

Sawfish in an aquarium. Photo © Nick Fox | Shutterstock

In fact, these two fish shared more in common than the aquarium they inhabited. Both belong to the family of sharks and rays, defined by having a skeleton of cartilage, not of bone. Secondly, they both penetrate into, and tolerate, fresh water. This is very unusual among the sharks and rays. Bull sharks, like most other sharks need to keep swimming to ensure adequate waterflow over their gills. Rays,which include sawfish, on the other hand, have a two neat pumps, the spiracles, that do the same job. So, a ray can quietly lie on the bottom, ventilating its gills without having to swim around. And that makes a sawfish relatively easy to keep in captivity.

So, about 13 years after that first encounter, I found myself embarking on a PhD to study how certain sharks and rays can adapt to fresh water. I chose the sawfish, and my mission was to catch them, keep them in captivity and transport them live to a laboratory in the south of France. There, using advanced radioactive isotope techniques we would be able to track the movements of salts and water into and out of the animal under different salinities.

After much searching my advisors suggested I look for sawfish in West Africa, specifically in the Casamance region in the south of Senegal. It was important to locate the juveniles; sawfish can grow to beyond 5m in length! However, soon after my arrival in Senegal, and with a bit of early persistence I located not one but two populations of sawfish. The large tooth sawfish, Pristis pristis was using the Gambia river, just 120km north of the Casmance in which to drop its young, while the smalltooth, Pristis pectinata, was doing the same near the mouth of the Casamance river. For logistical reasons, I chose the Casamance.

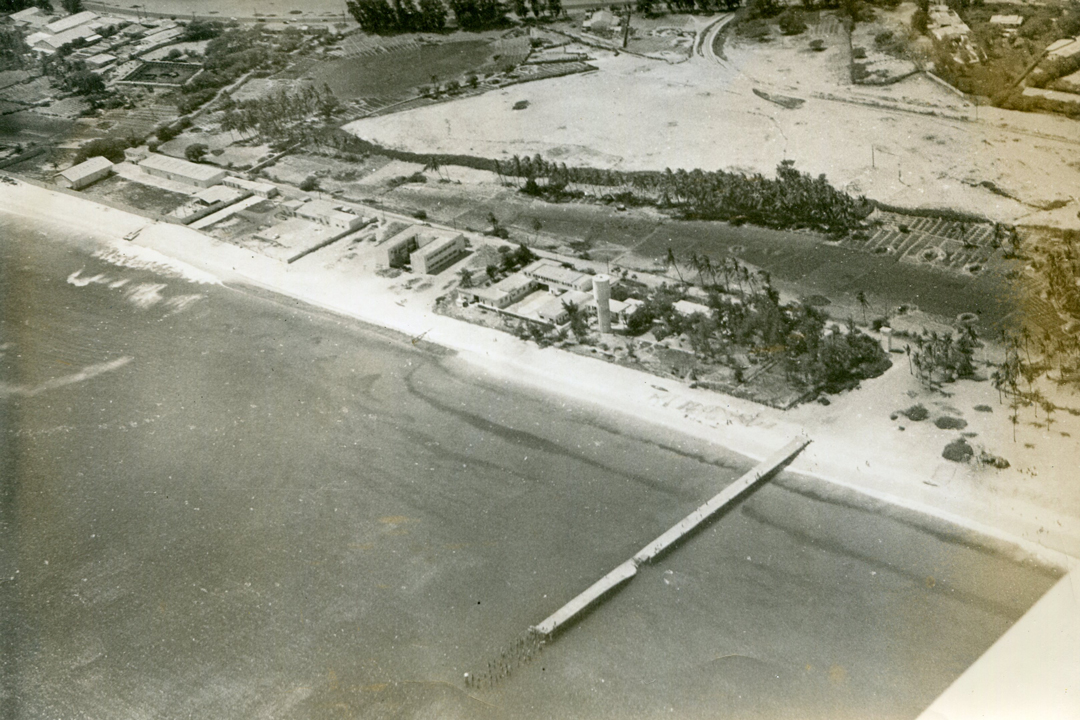

I was based at Thiaroye, near Dakar. It was a day’s hard road journey to reach the Casamance. I planned to use Thiaroye as a staging post before the final air-lift to France. So, the problems to overcome were to: build holding tanks in Thiaroye, build a holding facility in the Casamance, locate and catch enough sawfish for the project, transport them from the Casamance to Dakar and finally, find a way to transport them by regular passenger-jet flight to Nice.

And I had just eight months in which to do so.

Aerial photo of the Thairoye laboratory. The courtyard to the left of the water tower is where Nigel built the holding tanks.

The building of two holding tanks at the Thiaroye marine laboratory took time. I painted the freshly finished tanks with a special coating used to seal domestic fresh water containers. I could not risk anything leaching out from the cement and killing the fish. Each tank had an open sand-bed filter and a simple water circulation system. I covered the tanks with a sloping roof made of a local plant matting. We filled the tanks from the sea, having filtered the water through plankton-collecting nets.

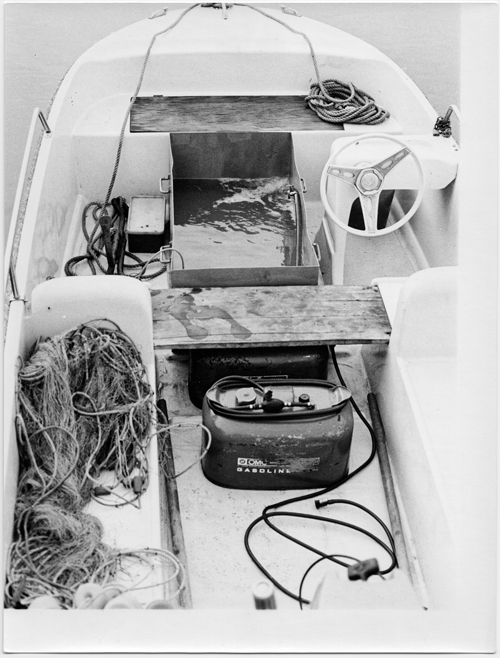

With the help of a local fisherman, Timothé, I found that baby sawfish were being dropped not far from the Casamance river mouth. The River Casamance is highly tidal, so they were being born into salty water. The location seemed ideal. We had decided to transport the sawfish from the Casamance to Thiaroye in the live-bait tanks of the station’s research vessel, the Laurent Amaro. She could enter the Casamance estuary, and the journey back north to Dakar could be done in under 24 hours.

The Laurent Amaro, with the net and holding tank. Photo © Nigel Downing Mukiwa

The first sawfish that Nigel and Timothé caught together, a small sawfish snagged in a net. Photo © Nigel Downing Mukiwa

The next problem was how to keep captured juvenile sawfish alive near the river mouth. At that time, the banks of the Casmance were lined with fish traps. Made from interlaced palm frond stems, these were robust enough to hold a sawfish, and allowed a good flow of water through the palisade. I commissioned a local fish-trap builder to make me a pen, and we put it in the water at Pointe St Georges.

Building the enclosure - the enclosure part constructed. Photo © Nigel Downing Mukiwa

At last all was ready, and late in November 1974 Timothé and I started fishing in earnest. But it was desperately late in the season. After several days of effort we netted six sawfish, put them in the enclosure, and called for the Laurent Amaro.

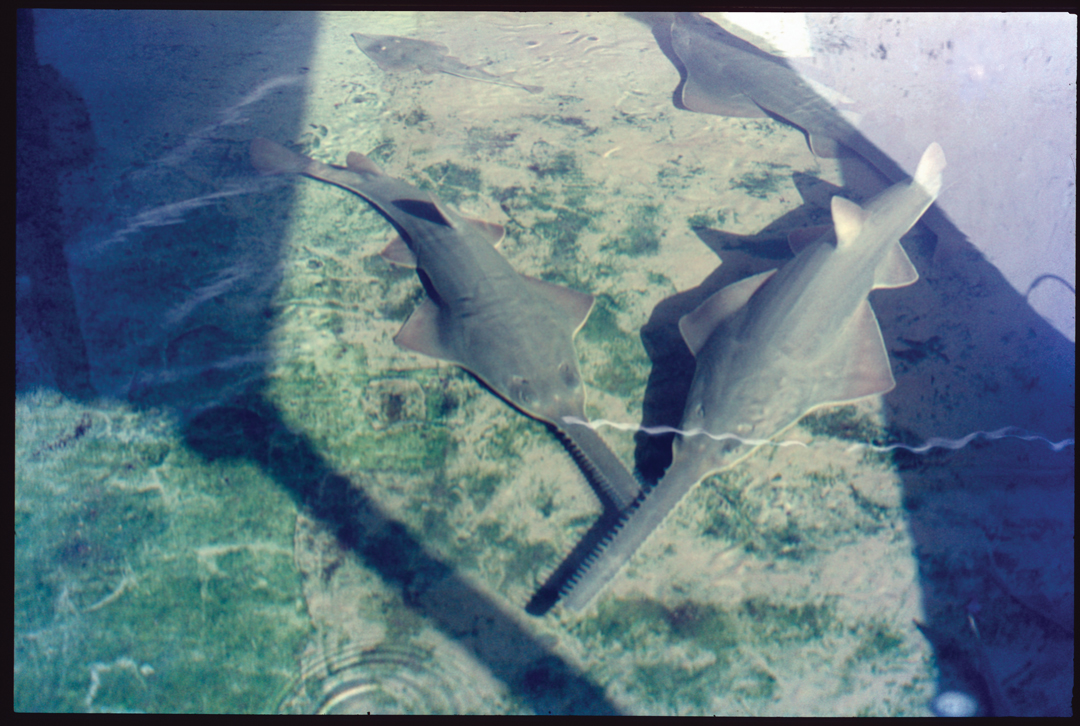

The waters of the Casamance are so murky that there was no way we could see our captives in the enclosure. But with patience you would occasionally spot a small saw emerge from the brown water and tap along the sides of the enclosure. We fed them shrimp, which I had found in the stomachs of dead juveniles and hoped for the best.

I drove back north to Dakar and accompanied the Laurent Amaro south. Dawn arrived in the Casamance on the 10 December as the vessel edged into the estuary. We launched the Zodiak, together with a transfer tank, and entered the enclosure. Unable to see the sawfish, I used a short section of fish trap material to protect my feet and legs, and gently corralled the sawfish into a corner. Once confined each animal was easily caught. Curiously there were only three sawfish left and we soon realised that three had escaped over the top on a very high tide; the enclosure had to be made higher. We transferred the fish to the live-bait tanks of the Laurent Amaro. Fresh seawater was circulated in the tanks as we cruised back up the West African Coast to Dakar. On arrival at the beach opposite the research station, the sawfish were once again caught and transported to their new holding tanks.

Patrice stands on the boat while they add to the enclosure's height, in order to stop the sawfish from escaping over the top. Photo © Nigel Downing Mukiwa

So far so good, but I had only three sawfish and I had run out of time! However, I had a very clear idea of when best to catch the fish, how to keep them alive in the river, how to transport them by sea and hopefully how to maintain them in a purpose-built facility.

Over the winter, all three sawfish succumbed to disease and died. I put it down to one central factor, and three possible causes. Certainly, the fundamental problem was water quality. I had not been in Dakar to look after them. Some of the plant material from the roof had fallen into the tanks, and the water temperature had dropped considerably.

However, given the progress I had made in such a short time, I was granted a further year to complete the work. I immediately built a third tank and redid the filtration and water circulation system. I built and added a U/V sterilisation circuit to help maintain water quality. And with plenty of time to spare, headed for the Casmance. The sawfish season was on!

By mid-July, Timothé and I had reconstructed the holding pen in the river and within just three days we had caught 15 smalltooth sawfish juveniles who were swimming around the pen. I called for the Laurent Amaro. I was told that she had broken down irretrievably and I could no longer rely on it. Furthermore, lightning had struck the holding tanks in Thiaroye and the entire electrical system had been destroyed. The water pumps had all burnt out in the power surge.

I could not be in two places at once. Timothé and I released all the sawfish back into the estuary, removed the enclosure and I headed north once more to lick my wounds and reassess.

Part 2. Call in the French Airforce

Time was running out, as were my options. The central problem now lay in the transport of the sawfish from the Casamance to Thiaroye. The sea route was no longer available. I briefly considered the road, but that journey was long, rough and required crossing the Gambia river on its notoriously fickle ferry. That left the air. The capital of the Casamance region, Ziguinchor had a good airstrip. As a young pilot I had used it in a light aircraft while trying to keep up my flying hours, and crossing Gambian airspace was not an issue. It was worth a shot.

And so, on 20th August 1975 I found myself smartened up and knocking at the door of the Colonel who was head of the local French Armée de l’Air. I explained my predicament, making sure to mention that these fish were destined for France, to the Villefrance laboratory of the French Atomic Energy Commission.

I suspect that nothing much was going on at that far-flung outpost of French airpower, because in no time a Commandant Doublet had been summoned to our meeting.

“Commandant!”

“Oui, mon Colonel.”

“This young Englishman needs our help.”

“Oui, mon Colonel.”

“He needs to transport tanks of sawfish from Ziguinchor to Dakar. Is that possible?”

“Well, we have just transported some baby giraffes from Cote D’Ivoire to Paris using the Nord Atlas, so, oui mon Colonel.”

“It will be a local training mission.”

“Bien sûr, mon Colonel!”

It was as easy as that.

On the way back home I heard a mewing from the rice field behind my house, where a bedraggled, abandoned kitten was crying for help. I took her home, adopted her and named her Le Commandant Doublet.

Part 3. The Final Race

The holding tanks were in a mess. I redid all the electricals. The burnt-out water pumps had their motors rewound. We recommissioned all three tanks. Meanwhile I had built 10 small transport tanks out of wood. I lined them with glass fibre and fitted carrying handles. Each tank would contain two sawfish. I had been assured that the Nord Atlas transport plane would fly the fish at low-level to reduce the chances of losing oxygen from the water and I fitted air bubblers to each tank for good measure.

I raced back to the Casamance as the season was drawing to its close. Timothé and I repositioned the sawfish enclosure upstream to Ziguinchor, close to the airstrip, and resumed fishing. The issue now was having to move each fish from the site of capture all the way to Ziguinchor, a journey that could take two hours in our small boat. It was painstakingly slow, and we lost one fish in the transfer.

By 12th September we had nine fish captured. As we approached the pen with another fish to put inside, to my horror I saw the carcass of a sawfish dangling by its rostrum from the vertical lines of the structure. We opened the enclosure, and I jumped in, searching for the living only to find the dead. Only two remained alive. We released them. It was a catastrophe. The waste made me sick to the heart. The project was over.

But why? What had killed the fish? What was wrong with the waters off Ziguinchor? As it turned out, nothing. However, when I jumped into the enclosure at Ziguinchor I noticed an immediate difference in the substrate compared to the enclosure substrate near the river mouth. There, off Point St. Georges the base of the pen was as smooth as a pavement, and very firm. The substrate contained some sand, and as the sawfish swam around the lighter particles of mud drifted up and away with the current leaving the harder sand behind. The sawfish had created their own, safe surface over which to swim. At Ziguinchor it was ooze. There was no sand. The sawfish had suffocated.

Part 4. The Last Option

“Why not try a swimming pool?”

“A swimming pool?”

“Yes, Dr Rollé down the road has a swimming pool. He never uses it.”

I was having dinner with friends in Ziguinchor, trying to face up to the enormity of failure and the loss of the fish.

“Are you serious?”, I said. “I would have to fill them with fresh water.”

“So, what? ” came the reply. “You keep telling us how these fish of yours can go from sea water to fresh water. That’s the whole point, isn’t it.?”

Yes, it was, I admitted to myself, as a glimmer of hope returned.

Dr Rollé agreed to the use of his pool, as did another Ziguinchor resident, but I was not going to put the euryhalinity of any fish to the test while stressing them with capture and transport.

I cleaned out the pools and found a salt merchant. It must have been the best deal he had ever done. Bag after bag of salt was transported to the pools and the salinity crept up to something approaching that at the site of capture near the river mouth.

Timothé and I were back in business. We returned to fish in desperation now as the season closed. The baby sawfish were also getting bigger, measuring a metre or more compared to the 70cm of a newly born. They were growing, and soon they would be gone.

Part 5. Farewell

Our final fishing effort began on 15th September and ended by the end of the month. By then Timothé and I had six sawfish swimming in M. Renard’s now salty swimming pool in Ziguinchor. We had to work fast because there was no water circulation system to maintain them for long. We had already lost several fish, and the French Airforce were getting impatient for their training flight to Ziguinchor.

Nigel removing a sawfish from M. Reynard’s pool on the day the Nord Atlas aircraft arrived. Photo © Nigel Downing Mukiwa

On the morning of 3rd October I waited in eager anticipation for the arrival of the Nord Atlas at Ziguinchor airport. It touched down and rumbled to a halt. We quickly unloaded seven transport tanks and headed for the pool. In no time the sawfish were on board the aircraft. When I think back to the moment we lifted off the Ziguinchor runway with that precious cargo and headed north, low over over the scrub of Senegal the sense of elation I felt is still palpable today. The sawfish survived the flight, and the transfer from the airport to their new home in Thiaroye. There they thrived! They grew! I even watched them hunt and successfully kill small fish I put into their tank, the first observation that sawfish do indeed use the teeth of their saw to impale living prey in midwater. I ran a successful experiment using a home-made “oxygen bag” to show how the fish could survive a 12 hour transfer by passenger jet to Europe…

Sawfish in the tank at Thiaroye. Photo © Nigel Downing Mukiwa

The French have two ways of saying goodbye. “Adieu” (go with God) is used when you are unlikely to be seeing one another again. “Au revoir” (see you again) is used in anticipation of another encounter. Although I begged for it, my project was given no further extension. It was understandable. From the time of arrival in West Africa to having the seven sawfish in their tank in Thiaroye it had taken almost 18 months. In the enthusiasm of my youth, I had estimated an unrealistic 8 months to complete the project.

In December 1975 I left Dakar with what I think was one of the biggest collections of sawfish rostra, skeletons, blood samples and morphological data anywhere in the world, and sadly no live fish. My hopes and dreams were over. But it was definitely “au revoir” to the sawfishes of The Gambia and the Casamance. I hope we can still find them today and not have to say “adieu”.