From the lab to the field – fish or shark? Threatened or not?

Great hammerhead shark. Photo © Wildestanimal | Shutterstock

Over a million sharks are killed every year either intentionally or unintentionally. In Ecuador, threatened species of sharks are frequently targeted for their meat, as well as their fins, for example, scalloped and smooth hammerheads (Fig. 1). Most of these sharks are landed without any distinguishing features, for example, they are missing most of their fins, their head and, to prevent rotting, sharks may also be landed without any organs (Fig. 2). They are also often kept on boats for a few days, or even weeks before they are taken to shore. So after laying for hours in the sun at a market, their colour starts to fade too.

Figure 1. When sharks have all identifying features, you might be able to tell it’s a species of hammerhead shark. But could you tell me whether it is a smooth (Sphyrna zygaena), scalloped (S. lewini) or great (S. mokarran) shark? These are juvenile smooth hammerhead (S. zygaena) sharks landed at Santa Rosa, Salinas, Ecuador. Photo © Guuske Tiktak | Manchester Metropolitan University

Smooth hammerhead shark. Photo © Alessandro De Maddalena | Shutterstock

To an expert, a shark without these identification features will be challenging to identify, to a non-expert, impossible. This is also similar to when shark fins have been dried in the sun. To an expert, a wet or dry fin may be difficult to identify by eye, but they may be able to use genetic tools to tell them apart. Becoming an expert in the field also takes time, for example, I have only recently started working in this area – and it took me one to two months before I was able to identify sharks confidently. To a non-expert, identifying the species by eye is impossible, and using genetic tools is costly, timely and requires the relevant knowledge and access to equipment. How can we tackle these issues?

Figure 2. When all fins, head and organs have been removed, could you still tell whether these are sharks? Or which species? Or that this is an endangered species of shark? These are scalloped hammerhead (Sphyrna lewini) sharks landed at Playita Mia, Manta, Ecuador. Photo © Guuske Tiktak | MMU.

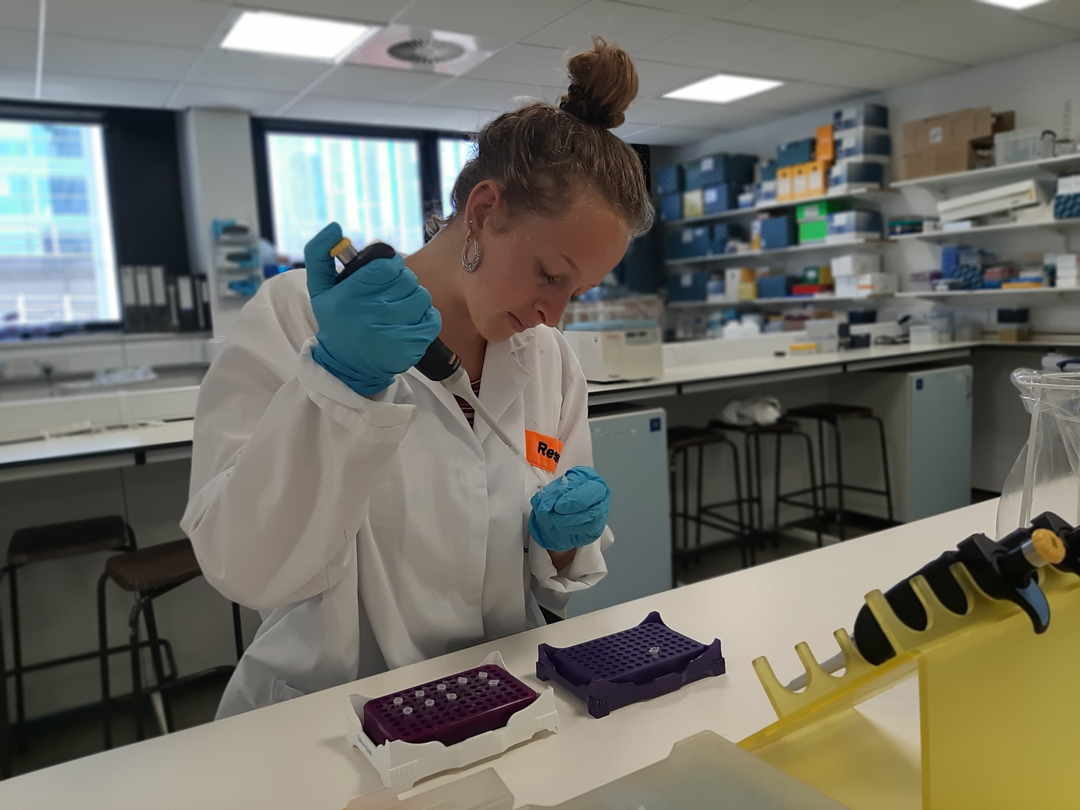

For the past few months, we’ve been getting busy in the lab (Fig. 3) – a little different to the usual fieldwork that you may expect. Many species of sharks are really closely related and telling them apart, both visually and genetically can be difficult. There are, however, regions of DNA that do allow us to tell them apart. Only a tiny piece of tissue or fin, about 25 mg (the size of a sand grain), is needed to carry out genetic analysis.

Figure 3. Guuske in the lab at MMU setting up an assay to test the scalloped hammerhead primers. Photo © Guuske Tiktak | MMU.

We are currently developing genetic markers for these regions in three threatened CITES species of hammerhead sharks, including scalloped (S. lewini), smooth (S. zygaena) and great (S. mokarran) hammerheads. A simple colour change, from pink to yellow, allows us to tell which one of these three hammerhead species is present from a small tissue or fin sample. So far two of the three hammerhead primers that we developed were completely species-specific, meaning that they only work on the target species – scalloped and great hammerhead shark – and not any other species, most importantly other elasmobranches. Once the genetic marker for the smooth hammerhead has been developed, we will move onto looking at the best way to extract the genetic material from the samples using a Lab-on-a-Chip, before testing our devices in the field.

Scalloped hammerhead shark. Photo © Andy Deitsch | Shutterstock