Fjordic Fin Whales

Working within Gitga’at First Nations territory is an incredible privilege for many reasons, but the thing that hooked me when I first came here a decade ago was the fin whales.

Photo © Janie Wray

The fin whale is an extraordinary species: the second largest animal on earth (ever), incredibly fast, frustratingly elusive, breathtakingly graceful, and unimaginably voracious. But it is the fact of the fin whale’s presence here, in the fjords of Northern BC specifically, that ignites my scientific imagination. Their use of these inland channels goes against everything we thought we knew.

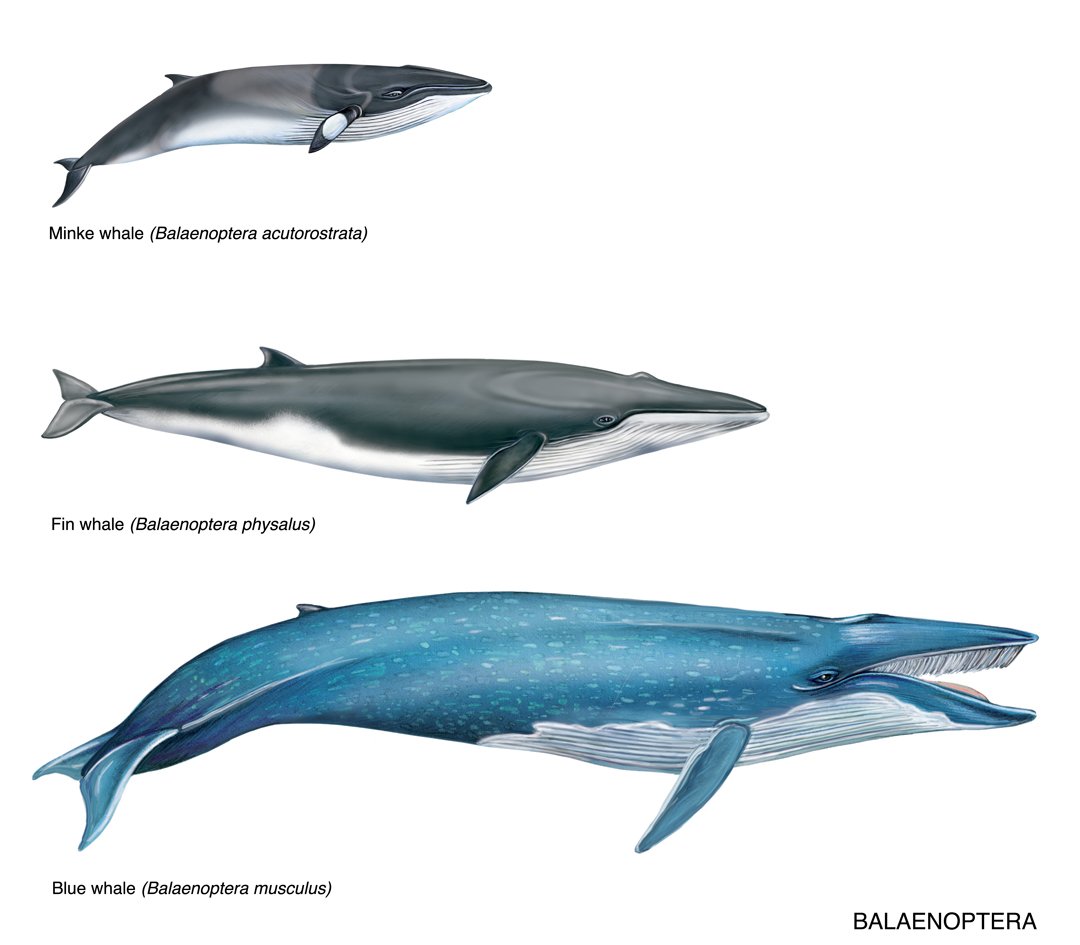

Artwork © annalisa e marina durante | Shutterstock

The historic concept of fin whale natural history has been coloured with the theme of Expanse: as one of the largest and fastest marine animals on earth, they can travel across entire ocean basins in mere weeks. Their songs are known for propagating audibly across hemispheres. Their appetites seem to be without horizon, and with every meal, their deep-diving lunge feeds scour the upper ocean for tons (literally) of prey.

But here in this fjord system, the fin whales are characterized instead by their confines: they wander through winding, labyrinthine channels day and night; their acoustic range is a fraction of what it is in open waters; they face the trappings of ripping tidal currents and swirling anomalies in salinity and temperature, even as they are funnelled to within a body’s length of the steep, sharp fjord walls. Everything about these fjordic fins seems to challenge convention. What are they doing in this place?

Photo © Janie Wray

The fin whale becomes even more intriguing when placed in historical context, especially the context of commercial whaling. Before the 20th century whaling, we have no idea where fin whales were and where they weren’t. Our first and only clues as to the pre-exploitation range and abundance of fin whales comes from the whaling record itself. They were hunted heavily in British Columbia, especially over the continental shelf and slope to the southwest of Haida Gwaii and Vancouver Island. Only a small portion of catches occurred within protected coastal channels. But of those inland kills, nearly all took place here, in the Kitimat Fjord System. According to the whaling data, this was the only fjord regularly used by B.C. fin whales. What were they doing here, and why weren’t they elsewhere in the mainland fjords?

Whaling removed fin whales from this place, and they did not return for nearly half a century. It was not until 2006 that the North Coast Cetacean Society (NCCS) confirmed that a fin whale had indeed returned to this fjord system. In 2007, we saw fin whales within their study area again, many more than the year before. In the years that followed, this pattern grew into a phenomenon. In 2011, there were fifty-two sightings! On one afternoon in 2010, a research vessel from DFO reported a group of no less than fifty fin whales feeding within a single channel! And in the decade since, fin whales have recovered their old status as a staple of the Kitimat Fjord System. In 2019, from our research station on (aptly named) Fin Island, we logged over 538 visual detections and more than 5,000 acoustic detections of fin whales!

Photo © North Coast Cetacean Society 2019

The British Columbia fin whales are recovering. Amazingly, this is still the only fjord where fin whales can regularly be found. The old pattern of the whaling and pre-whaling era has been re-established. Again: what is it about this place?

Perhaps this is what I love so much about these fin whales: they can’t be understood without understanding their place. And maybe the reverse is also true: can we understand this place without understanding the way these fin whales fit into it?

Photo © Juan Gracia | Shutterstock

The mystery of the fin whales’ presence here is equalled by that of their future. How many fin whales can this place support, and for how long? Despite the remoteness of these waters and the stewardship of the Gitga’at First Nation and NCCS, this fjord is by no means pristine. The slaughter of whales may be over, but it was merely replaced by the pillage of their habitat. Fleets of small vessels visit these waters every year, dumping pollutants and noise that surely make these waters less attractive. Cruise ships plough through these corridors, and LNG tanker traffic is staged to expand drastically. Will these fjords ever be as important to fin whales as they were a century ago? Should we be excited or concerned that the fin whales have rediscovered this place?

With time, these questions may answer themselves. Meanwhile, we continue to strive for understanding. How do the fins fit in here? What is it about this place that is so special? What can we do to keep it that way?