First Insights into the South Ari Marine Protected Area: The Potential of Whale Shark Research

The Maldives archipelago, encompassing roughly 3 500 square kilometres (1 350 square miles) of reef, is among the largest modern tropical carbonate areas in the world and a major hotspot for marine biodiversity. Formed roughly 65 million years ago, as the Indian Plate moved northward over the Mauritius hotspot (an underwater seamount volcano), the islands’ warm and stable reefs acted as a refugium during the multiple quaternary glaciations (2.6 million years ago until the present) and allowed the preservation and generation of the astonishing biodiversity we observe today. In addition, their volcanic origin shaped them in a way that provides key bathymetric features, such as shallow reef areas close to steep slopes leading into the meso- and bathy-pelagic zones. Such reef geomorphology induces upwelling, during which nutrient-rich waters rise, increasing primary productivity. This in turn attracts a variety of fascinating filter-feeding species, including the endangered whale shark Rhincodon typus, or fehurihi as it is called by the locals.

Dhigurah and other islands of the Alif Dhaal Atoll. Photo © Dawid Piotr Szlaga | Wild Island Pictures

The South Ari Marine Protected Area (S.A. MPA) is the country’s largest at 42 square kilometres (16 square miles) and extends along the seaward fringe of Ari Atoll. This seascape fits the requirements of a nursery location for sharks particularly well. Large filter feeders aggregate year-round and are thought to use the shallow areas to thermoregulate after diving deep to feed on their planktonic prey, which migrates to depths during the day. In 2015, while Giulia was working for the Maldives Whale Shark Research Programme, it was in this region that she decided to start finding data about whale sharks in a new way – by collecting their poo!

Locals of Dhigurah pulling boat on land for repairs and maintenance. Photo © Dawid Piotr Szlaga | Wild Island Pictures

Thinking back to 2015, Giulia recalls nostalgically, ‘After a day of surveying whale sharks, the best place to end it would be at the home of Gasimbe, our boat’s captain, and spend some time with his nephews on the kitchen’s joali (a traditional chair made entirely from a coconut tree) while waiting to taste the delicious traditional fish curry.’ Experiencing this lifestyle at first hand forcefully brought home to her how dependent on the sea’s goods families like that of Gasimbe were. Before 1965, when he joined the conservation programme, Gasimbe had been a fisherman who would take part in whale shark hunts for the shark’s flesh and oil-filled livers. Such a hunt would require a huge collaborative effort and unite the entire local community. Today, Maldivian people still feel culturally connected to these gentle giants, although since the 1980s they see them in a completely different way: whale sharks have become of inestimable value to the tourism industry, a leading pillar of the nation’s economy.

From left to right: Irthisham Zareer (MWSRP), Alina Wieczorek, Gasimbe's granddaughters and Giulia Donati. Photo © Dawid Piotr Szlaga | Wild Island Pictures

Unregulated tourism, leading to boat strikes and changes in shark behaviour, is now one of the biggest threats to whale sharks worldwide. Other potential threats include habitat loss due to coral bleaching, and ever-increasing plastic pollution. Alina, whose research specialises in the abundance and impact of microplastics, explains that filter-feeding species such as the whale shark are particularly susceptible to plastic pollution and are prone to ingesting microplastics as they filter large amounts of water to obtain their planktonic prey.

Microplastics from Dhigurah island shores. Photo © Dawid Piotr Szlaga | Wild Island Pictures

Oil-soaked plastic litter floating in the water at the ferry port in Male. Photo © Dawid Piotr Szlaga | Wild Island Pictures

Plastic bag stuck on dead coral reef. Photo © Dawid Piotr Szlaga | Wild Island Pictures

Many other species are affected by plastic pollution and habitat loss inflicted by humans, but Alina and Giulia explain that whale sharks, due to their cultural significance, economic importance in the country and charismatic appeal around the globe, can act as umbrella species for an entire ecosystem. Research on whale sharks can be useful for directing various conservation management strategies and the preservation of their habitat will benefit not only local inhabitants like Gasimbe’s family, whose lives are entirely dependent on the sea, but also the entire global population, as functioning marine ecosystems are key to the health of our oceans and our planet.

Tourists swimming with whale shark in South Ari Marine Protected Area. Photo © Katie Hindle

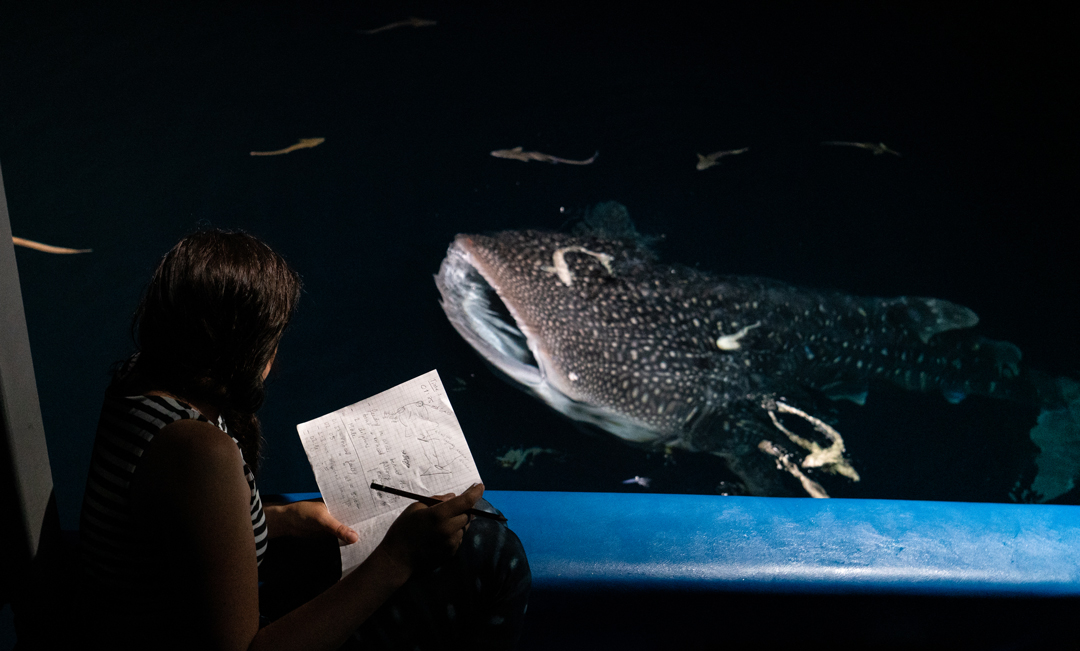

Giulia Donati recording whale shark encounter of suction feeding juvenile whale shark at night. Photo © Dawid Piotr Szlaga | Wild Island Pictures

***References

Cagua EF, Collins N, Hancock J, Rees R. Whale shark economics: a valuation of wildlife tourism in South Ari Atoll, Maldives. PeerJ. 2014 Aug 12; 2:e515.

Copping JP, Stewart BD, McClean CJ, Hancock J, Rees R. Does bathymetry drive coastal whale shark (Rhincodon typus) aggregations? PeerJ. 2018 Jun 8; 6:e4904.

Germanov ES, Marshall AD, Bejder L, Fossi MC, Loneragan NR. Microplastics: no small problem for filter-feeding megafauna. Trends in Ecology & Evolution. 2018 Apr 1; 33(4):227–32.

Pellissier L, Leprieur F, Parravicini V, Cowman PF, Kulbicki M, Litsios G, Olsen SM, Wisz MS, Bellwood DR, Mouillot D. Quaternary coral reef refugia preserved fish diversity. Science. 2014 May 30; 344(6187):1016–19.

Perry CT, Figueiredo J, Vaudo JJ, Hancock J, Rees R, Shivji M. Comparing length-measurement methods and estimating growth parameters of free-swimming whale sharks (Rhincodon typus) near the South Ari Atoll, Maldives. Marine and Freshwater Research. 2018 Oct 5; 69(10):1487–95.