Features of the great white shark population of Seal Island, False Bay

Recently, there has been a lot of scientific debate around the size of the South African white shark population, with estimates ranging from 500 to 2000 sharks. However, neither of these are large numbers, especially when one considers there are approximately 3200 wild lions (9000 if you count those in captivity) and 5000 black rhino left in South Africa. What is not in debate is the white sharks’ vulnerability to growing pressures from fisheries (especially as bycatch in demersal shark longlines and gill nets), culling with the use of shark nets and loss of prey across their range. It is therefore essential that we study and monitor their populations.

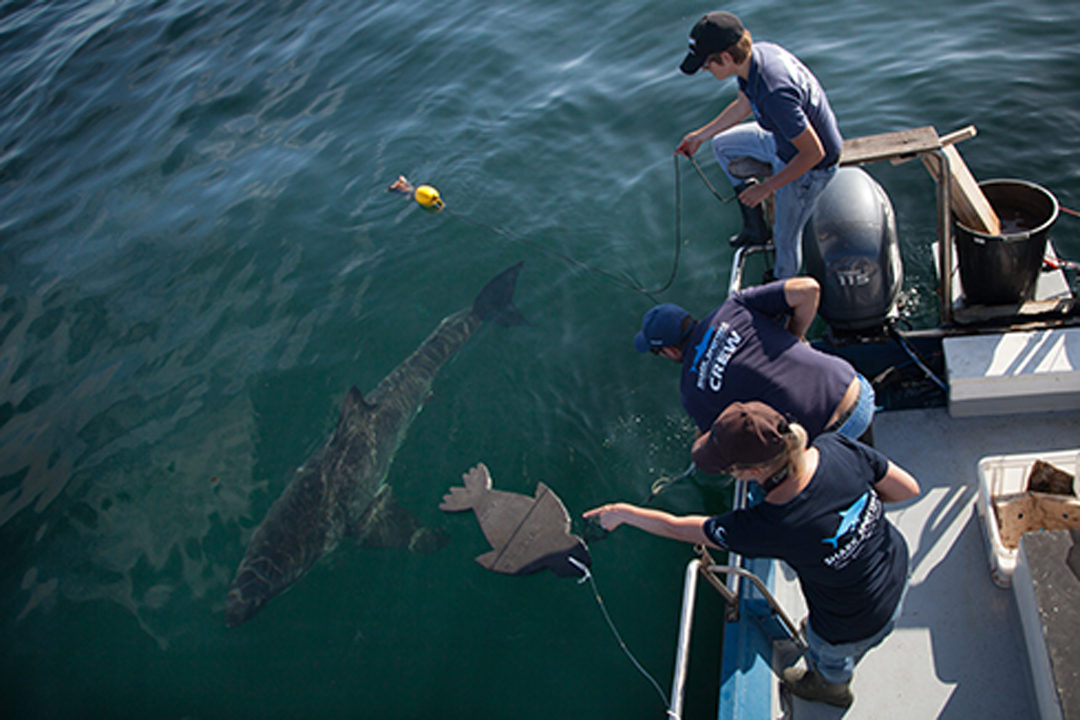

Photo © Morne Hardenberg

We recently published the findings of research we conducted at Seal Island, False Bay over a 9-year period from 2004 – 2012. We documented sighting rates of male and female white sharks of various sizes, and used photo-identification (photo-ID) of individual sharks to examine their annual visitation patterns. In total, we recorded 1105 shark sightings and photo-ID’d 303 unique individuals, during 557 hours at sea.

Photo © Alison Kock

We learnt a lot in this time, but more than that we have been incredibly fortunate to spend so much time with these incredible animals.

- We found that the shark sightings varied considerably between years – some years had low sighting rates (1.0 sharks / hour), others high, with a peak in sightings during 2005-2006 (3.2 sharks / hour). This peak corresponded to a spate of shark bites in False Bay (3 fatal incidents and lots of shark-human conflict).

- Overall the sighting rate for Seal Island declined, although the trend was not statistically significant. However, we don’t have enough information to determine whether this is indicative of a population decline, or due to a change in distribution. Shark distributions are influenced by environmental factors, prey availability and at what stage they are in their life-cycle.

- We found that most of the white sharks visiting Seal Island are immature (teenager age) with no young-of-the-year (shark pups) and relatively few adults, especially adult females. We also compared the size distribution from Seal Island to other major aggregation sites in South Africa and confirmed that the island has the largest (3.5 meter) average size sharks, with a general increase in shark size from east to south along the coast.

- The overall ratio of males to females was the same for Seal Island, unlike we’ve documented for the inshore areas of False Bay, where females and males segregate over summer, with more females inshore. However, there was a difference in sex ratios by year and month at Seal Island, with males becoming more prominent in later years and peak sightings for males in June and July (but not for females).

- Based on these results, Seal Island is best described as a seasonal feeding ground for white sharks in their teenage and sub-adult years, and not a nursery area or adult aggregation site. No pregnant females were recorded.

- Of the 303 unique individuals, most (215) were not re-sighted again, indicative of transient behaviour. On the other hand, the rest of the individuals (88) showed site-fidelity (recorded in more than 1 year) to Seal Island. The greatest number of resightings for a male was 21 times over 9 years, and 16 times for a female over four years. The longest periods between resightings were 6.8 years for a male and 6.2 years for a female.

- After visiting Seal Island consecutively for 2 – 3 years, female sharks approaching sexual maturity (>4.5 meters) were rarely seen again and few mature females were recorded at Seal Island or any of the South African aggregation sites – indicating they use other habitats, possibly offshore, to breed.

Photo © Alison Kock

Our study has provided important information on which portion of the white shark population uses Seal Island, patterns of visitation and identified a decline in sightings, but it does have some limitations. While we spent hundreds of hours documenting the sharks that visited the island, our effort was variable and we couldn’t spend all our time out there (as much as we would have liked to). Not all sharks are attracted to the research boat, sharks don’t have to come to the surface if they don’t want to, and it is possible that some sharks are dominant over others, thus possibly biasing some results. However, we did account for the variable effort in analyses and considered alternative explanations for some results as described in more detail in the paper. But, probably more importantly we must need to remember that white sharks can live >70 years and such this study only provides a snapshot into their lives.

Photo © Jay Caboz

White sharks are important top predators that feed on a variety of squids, fish, seals, and other sharks and therefore they have the ability to influence what our ecosystems look like and how they function. Understanding the reasons for the variable sighting rates over the years and given the uncertainty of what the decline in sighting rates mean, it is crucial for their conservation that future research be directed in this area and that monitoring of the population continues. Furthermore, understanding what drives the high and low sightings rates over time can help us predict years when shark activity could be expected to be higher than normal and thus could be used in shark safety campaigns to reduce human-shark conflict.

This study was led by Adrian Hewitt, a MSc student at the University of Cape Town with co-authors Prof Charles Griffiths (University of Cape Town) and Prof Tony Booth (Rhodes University).