Cosmopolitan tiger sharks

Words by: Ryan and Clare Daly

The end of the summer season is an exciting time for us as we download information from our underwater acoustic receivers. The receivers record the presence (and absence) of tagged tiger sharks at our study site in the Ponta do Ouro Partial Marine Reserve in southern Mozambique. For nine months we have been anxiously waiting to retrieve the receivers and it’s always a relief to get the data safely downloaded.

A tiger shark in the Ponta do Ouro Partial Marine Reserve Where has this shark been and where is it going?. © Photo by Ryan Daly

All of our tagged tiger sharks were detected at our study site on the latest download. But we also had some visitors: preliminary data show that tiger sharks tagged off Reunion Island in the Indian Ocean by researchers from the Institut de Recherche pour le Développement (IRD) may have visited the Ponta do Ouro reefs. These sharks have travelled a long way – nearly 2,300 kilometres – from the other side of Madagascar and it makes us wonder: are our tiger sharks swimming to Reunion as the Reunion sharks come here?

In Ponta do Ouro Partial Marine Reserve, ranger Filimone Francisco Javane holds up a retrieved receiver Data stored on this device will tell us about the presence and absence of tagged sharks at our study site. © Photo by Jenny Stromvoll

This is a significant question. Why? Because Reunion is planning a shark-culling programme in response to shark bites. Although we don’t yet know how connected tiger shark populations may be in the Indian Ocean, it is worth realising that killing sharks in one location may negatively impact their presence in other areas. Aside from their ecological importance, tiger sharks are a special tourism attraction for South Africa. A 2009 study found them worth approximately US$1-million in direct annual expenditures. Thus, there may be economic as well as ecological implications relating to Reunion’s decision to cull tiger sharks.

Tiger sharks tagged at Reunion Island were recorded on receivers in the Ponta do Ouro Partial Marine Reserve and at the South African/Mozambican border This suggests that tiger sharks in the south-western Indian Ocean may be more cosmopolitan than previously thought. © Photo by Google Maps

Unfortunately, Reunion’s culling programme isn’t the only risk faced by tiger sharks in the region: shark nets in South Africa and shark fishing in Mozambique are also hazards for them. There is thus a need firstly to establish how often tiger sharks are exposed to these risks, and secondly to find out to what extent marine protected area habitats are important as refuges for them. As we collect more data about the movements of tiger sharks from our tagging study, we hope to improve our understanding of the balance between risks and refuges for the species and propose a more effective conservation management strategy for it in the south-western Indian Ocean.

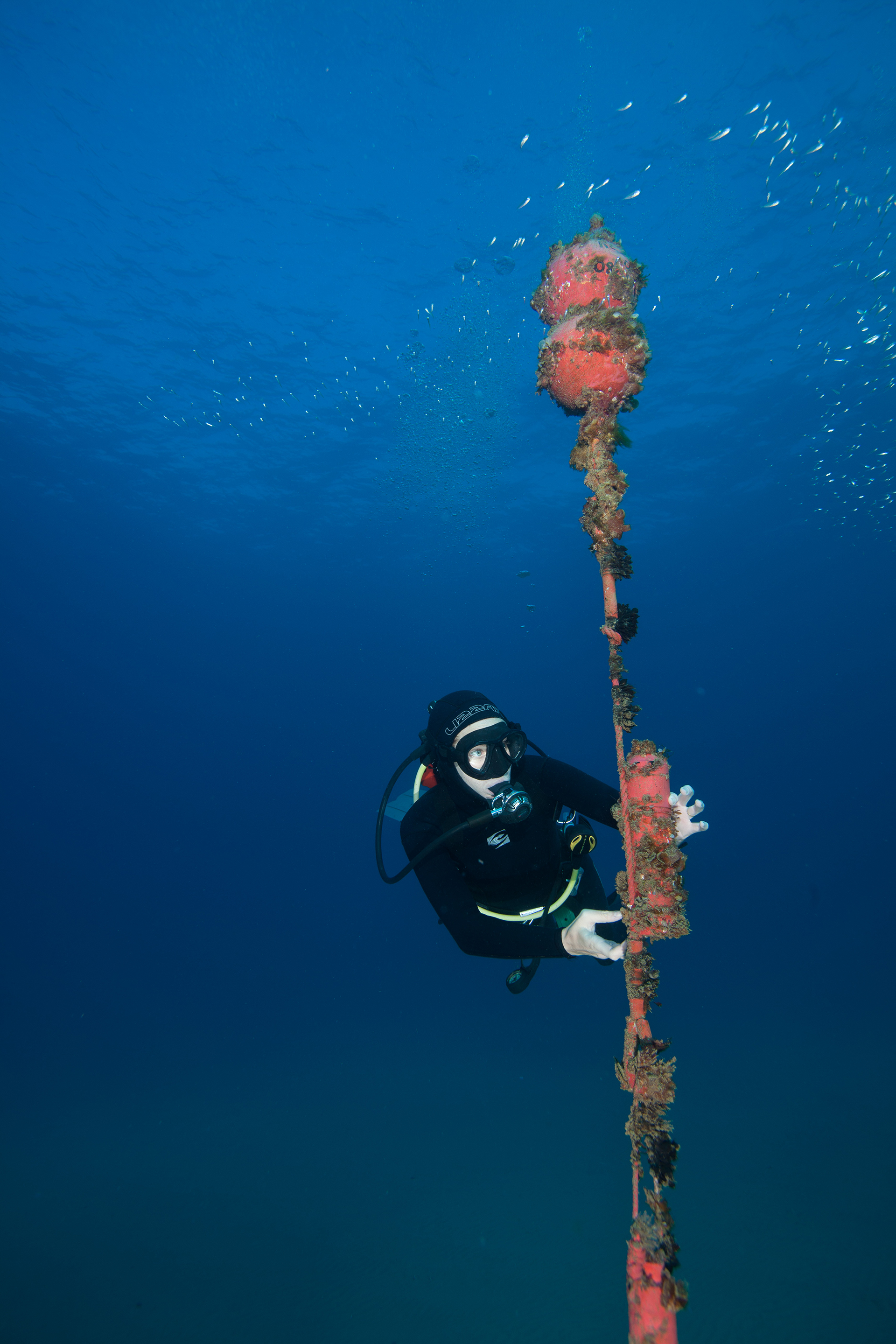

Clare Daly inspects one of the receivers moored to a rope and buoy at our study siteThese receivers form part of a larger network in the region, the Acoustic Tracking Array Platform, which is maintained by the South African Institute for Aquatic Biodiversity (http://saiab.co.za/atap.htm) and supported by the Ocean Tracking Network. © Photo by Ryan Daly