Connecting for Conservation

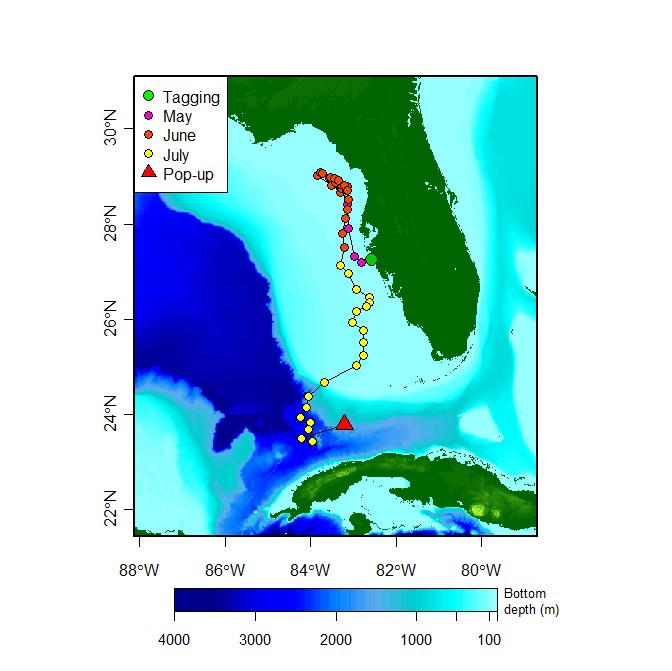

Over the past two years, we at the Mote Marine Laboratory in Florida have linked up with researchers from Cuba and Mexico, made some amazing friends and established connections with stakeholders across the Gulf of Mexico – all with the goal of learning more about spotted eagle rays. In one of our recent blogs, we described how we had just fitted a pop-up satellite tag to a large female ray (SER 389) off Sarasota, Florida, to see where she would go. When the tag reported three months later, she had swum up off the west coast of Florida and then down towards Cuba before the tag came off.

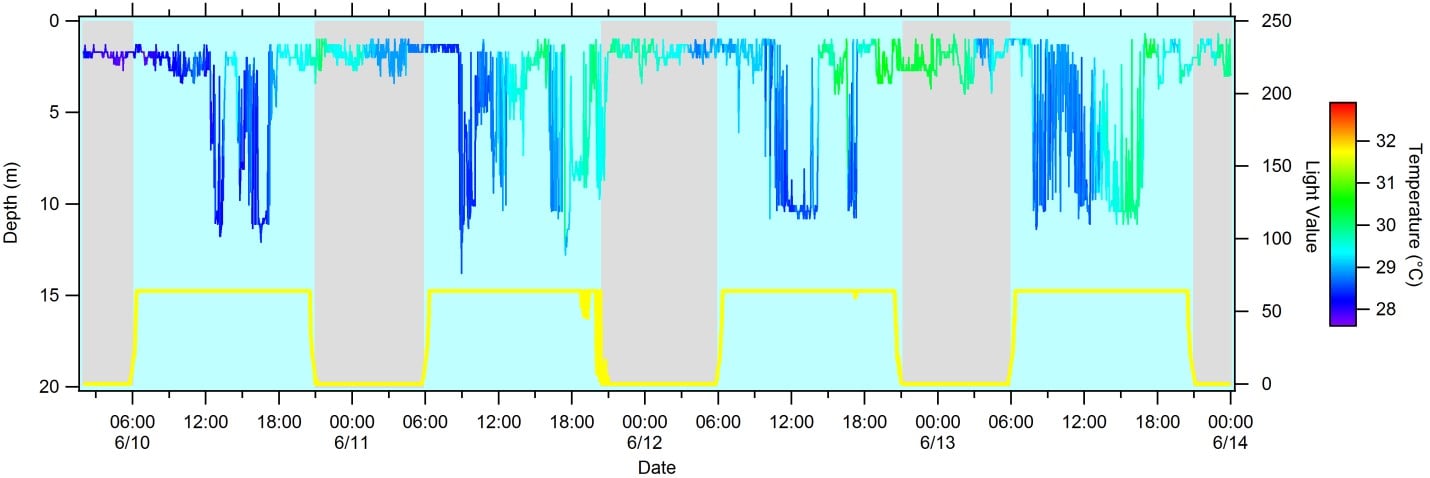

This ray’s dive profile showed that she often dived during the day (to a maximum depth of 24.5 metres) and stayed close to the surface at night.

Depth, temperature, and light profile from June 10-14, 2013. The shadow boxes represent nighttime and are based on the tag’s measured light values (yellow trace; right axis).

From SER 389 and some of our genetics work we learned that spotted eagle rays probably cross international borders during their seasonal movements and therefore warrant collaborative study with researchers in several countries spanning the Gulf of Mexico, Caribbean Sea and Western Atlantic. Therefore in February 2014 Dr Bob Hueter (director of Mote’s Center for Shark Research), Captain Peter Hull (head of Mote’s Marine Operations) and I travelled to Cuba to meet with colleagues Jorge Angulo and Alexei Ruiz at the University of Havana’s Center for Marine Research (Centro de Investigaciones Marinas; CIM). Our aims were to learn more about the impact of fisheries on spotted eagle rays (and other elasmobranchs) and to investigate potential hotspots for sighting these large, beautiful pelagic flyers in reef areas.

Project PI Kim Bassos-Hull and Cuban colleague Alexei Ruiz (University of Havana’s Center for Marine Research) take a genetics sample from a piece of spotted eagle ray pectoral fin at a fishing port along northwest coast of Cuba. Photo credit: Robert Hueter – Mote Marine Lab

While in Cuba we travelled with CIM staff and students to fishing ports to speak to fishermen and learn more about their catches and to help collect samples. One thing we learned is that in Cuba much of the catch comes to port in pieces instead of whole, which makes it difficult to determine the species and the size of the catch. Luckily, with spotted eagle rays they leave a small portion of the skin on, and the distinctive spot markings make it easier to identify the pieces. The Cuban fishermen told us they typically catch more spotted eagle rays in winter and especially after cold fronts and windy weather (probably when the water is murkier and the rays cannot see the nets).

Mote and CIM staff taking a shore break at Punta Frances, Isla de la Juventud, Cuba. Photo credit: Kim Bassos-Hull – Mote Marine Lab

Our other objective was to visit an area where our Cuban research colleagues sometimes observe spotted eagle rays along the reefs in an ecotourism dive area (also a marine protected area) called Punta Frances on Isla de la Juventud. We did not see any spotted eagle rays on this trip, but we discussed some potential research ideas for sighting, photographing and measuring them in some of the popular dive areas around Cuba and for engaging divers to help report sightings. This is something we will be working towards in 2015.

Project PIs Kim Bassos-Hull and Bob Hueter search for spotted eagle rays of Punta Frances, Cuba. Photo credit: Peter Hull – Mote Marine Lab

The other country involved in our tri-national research on spotted eagle rays is Mexico. In an earlier blog we mentioned collaborating with Dr Juan Carlos Perez Jimenez from ECOSUR in Campeche, Mexico. Juan Carlos and his team study elasmobranch fisheries along the western Yucatan peninsula to learn more about the species’ life history and the sustainability of the fisheries. They have a very good working relationship with many of the fishermen and because of this Dr Matt Ajemian (Texas A&M Harte Research Institute), Krystan Wilkinson (University of Florida PhD student) and I were able to travel to Campeche in March 2014 to work with Juan Carlos, his research assistant Ivan Mendez and ECOSUR students as well as the fishermen of Sebaplaya.

Fishermen near Sebaplaya Mexico pull in a spotted eagle ray for researchers to tag and release. Photo credit: Kim Bassos-Hull – Mote Marine Lab

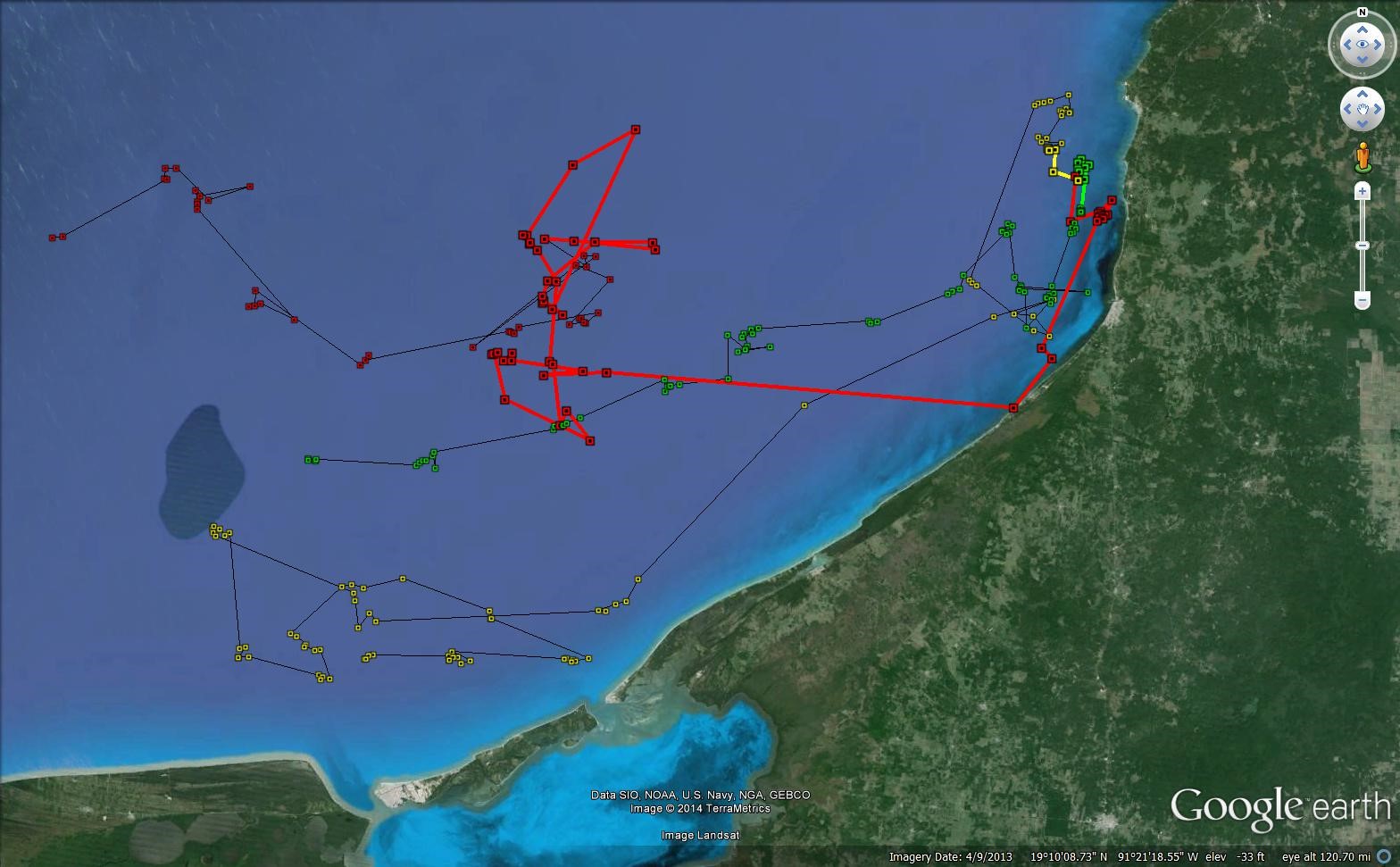

Our purpose was to tag and live-release spotted eagle rays that had been caught in the nets. In total seven spotted eagle rays were caught and three of the rays were fitted with towed-SPOT satellite tags, two of which (both on smaller males) only worked for a few days. The third, on a larger female, stayed on for several weeks and demonstrated movements alongshore (including the immediate coastline) as well as a prolonged period of activity offshore, near an area where drilling for oil and gas was taking place. Although the findings are preliminary, they demonstrate the potential link between offshore and coastal habitats for these larger rays, and other areas of potential interaction with human activities.

Locations from the SPOT5 tagging of three spotted eagle rays off the coast of Campeche, Mexico on March 8, 2014. Argos locations with a quality rating of 3,2,1,0 and A are shown. Bold lines indicate where the tag was likely still attached on the ray

Another objective on this trip was to train ECOSUR students how to handle and measure live rays and collect stomachs from fisheries-caught rays so that we could begin to look at gut contents – what are spotted eagle rays eating? We were lucky to have Matt along, as he is an expert in identifying prey from stomach contents and back at the lab he was able to train ECOSUR students (and myself!) in extraction and identification methods. The next step of this project is to add a genetic component to better categorise the prey items. Krystan, an expert in GIS and seascape mapping, was able to share with the ECOSUR students what we have learned about the spotted eagle rays’ use of habitat in Sarasota in relation to the state of the tides and the distribution of predators and competitors. And lastly, Juan Carlos and his team told us about their educational outreach activities and how they are engaging with the next generation of scientists in Mexico.

Matt Ajemian (Texas A&M Harte Research Institute) shows ECOSUR staff and students how to examine stomach contents from a spotted eagle ray in Campeche, Mexico. Photo credit: Kim Bassos-Hull – Mote Marine Lab

In May 2014 we were able to bring ECOSUR student Abish Garcia to Mote to participate in our programme activities for two months. Training students in conservation methods and promoting awareness about spotted eagle rays and other elasmobranchs are important objectives of our project. Abish, along with several high school and college interns, got a chance to have hands-on training with spotted eagle rays, devil rays and cownose rays, as well as to participate in shark census surveys. While Abish was in Sarasota, she participated in our educational activities too, such as helping dissect sharks with Mote’s Gills Club (a club for girls who love sharks and rays) and working at our outreach booth at World Ocean Day, telling visitors about what spotted eagle rays eat and how we identify them by their spot patterns.

Mexican student Abish Garcia (left) gets ready to set a spaghetti tag on a spotted eagle ray. Photo credit: Kim Bassos-Hull – Mote Marine Lab

A little earlier in the spring, Breanna DeGroot had joined our team as a college intern and, along with Mote research assistant Rachel Dreyer, helped to bring Doty (our spotted eagle ray mascot) to life. Doty made her first appearance at the Florida Keys Ocean Fest in March 2014 and since then has attended several other events, such as Shark Con in Tampa, World Ocean Day and Night of Fish Fun and Fright at Mote, where she swam around with her buddy Hammer (a hammerhead shark made out of recycled materials).

(From left to right) Mote intern Bella Genta, Project PI Kim Bassos-Hull, Mote research intern Breanna DeGroot (aka “Doty” the spotted eagle ray), and Mote intern Sean Russell show off cool things about rays at Shark Con in Tampa, FL. Photo credit: Kim Bassos-Hull – Mote Marine Lab

In June 2014 we reached an important milestone: our first major publication which reported on the initial four years of our research on the spotted eagle rays off the Florida coast. Professional outreach through publishing scientific findings in peer-reviewed journals is an important objective of our study. ‘Life history and seasonal occurrence of the spotted eagle ray, Aetobatus narinari, in the eastern Gulf of Mexico’ was published in Environmental Biology of Fishes. A few key findings that we documented were that spotted eagle rays are found mostly in spring, summer and autumn, with large individuals in spring and pups in the autumn months. Males reach sexual maturity at about 127-cm disc width, and males and females in general are similar weights for their respective sizes. One of the cooler findings was that spotted eagle rays had some degree of site fidelity to the area, as we had 21 individuals recaptured from five days to 1,293 days apart and we were able to obtain the first-ever growth rates from spotted eagle rays in the wild.

With research colleague (and former Mote College intern) Jennifer Newby as first author, we also published a manuscript on the social structure and kinship of spotted eagle rays found in groups. These findings showed there was no direct kinship in these groups. Two other manuscripts from this research (one on spotted eagle ray population structure in the Gulf of Mexico and the other on spotted eagle ray distribution in relation to predators and competitors and tidal state) have been submitted and are in review.

To round off our research and educational activities in 2014, I travelled to the California Academy of Sciences (CAS) in San Francisco, California, in September and then back to Florida. While at CAS, and with research collaborator Anna Sellas (lab manager for the CAS Center for Genomic Studies), I had the really cool experience of presenting our research to a public audience in a large planetarium dome as part of a nightlife series. Imagine an eagle ray two storeys tall swimming above your head on a dome screen!

Visiting Mexican colleague Ixchel Garcia (Blue Core) with a spotted eagle ray just prior to release near Sarasota, Florida. Photo credit: Kim Bassos-Hull – Mote Marine Lab

Back in Florida in October, Mexican research colleagues Ivan Mendez from ECOSUR and Ixchel Garcia Carrillo from Blue Core in Quintana Roo joined us to gain some hands-on field experience and share their research with Mote’s high school interns and Disney’s Living Seas and Florida Aquarium aquarists. During our field work we worked up several small spotted eagle ray pups and had the opportunity to capture, measure, tag and release a group of devil rays Mobula hypostoma. The devil ray is a smaller filter-feeding ray (imagine a mini manta) and we have started to investigate what prey it is keying in on by doing plankton tows near where individuals have been seen.

Visiting Mexican colleague Ixchel Garcia (Blue Core) measures a devil ray (Mobula hypostoma) while Mote intern Breanna DeGroot supports it, Sarasota Bay, Florida. Photo credit: Kim Bassos-Hull – Mote Marine Lab

Although Ivan had to head back to Mexico in early November, Ixchel was able to stay to the end of the month and participate in some of our outreach in the Florida Keys. Through a collaboration with dive shops, for two years we have been collecting spotted eagle ray sightings from divers throughout the Florida Keys. These divers list spotted eagle rays in their top three list of creatures to see while diving the reefs (sharks and turtles being the other two). Our next step is to engage further with these dive eco-tour operators (in Florida, and we’ll initiate a programme in Mexico and Cuba too) and set up a dedicated survey to learn more about these large, beautiful rays – the ‘queens of the reef’.