Uncovering the secret movements of silky sharks

Forged by the clash of tectonic titans over millions of years, the Galápagos Islands are standing echoes of the past. A look into the rich waters that surround the volcanic archipelago offers a similar window through time, to when the underwater world was not so impacted by our own. The islands are revered as the ‘sharkiest’ place on the planet, home to spectacular schools of scalloped hammerheads and famed whale shark meet-ups. Now the travel habits of a lesser known species might offer clues about how to keep it that way.

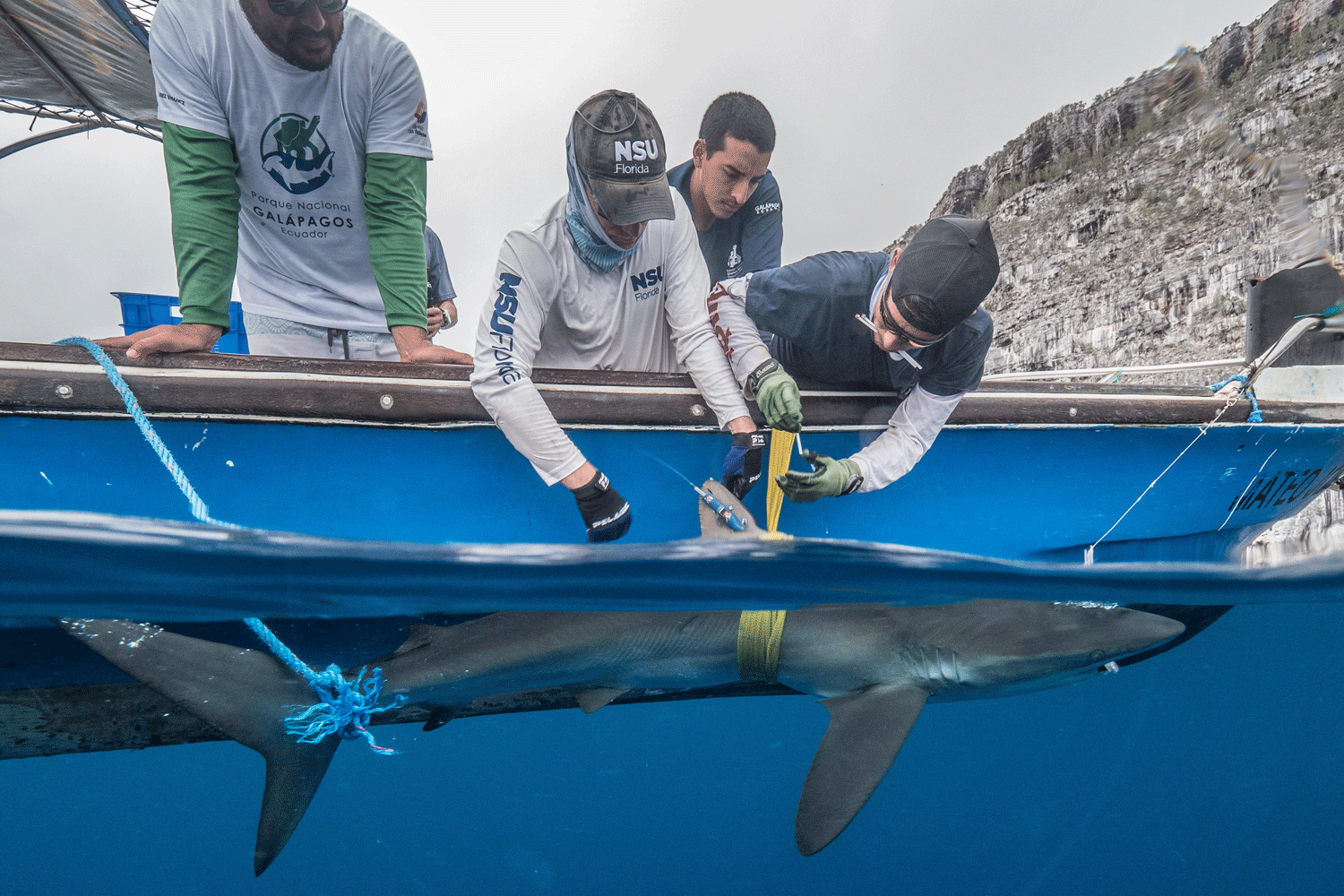

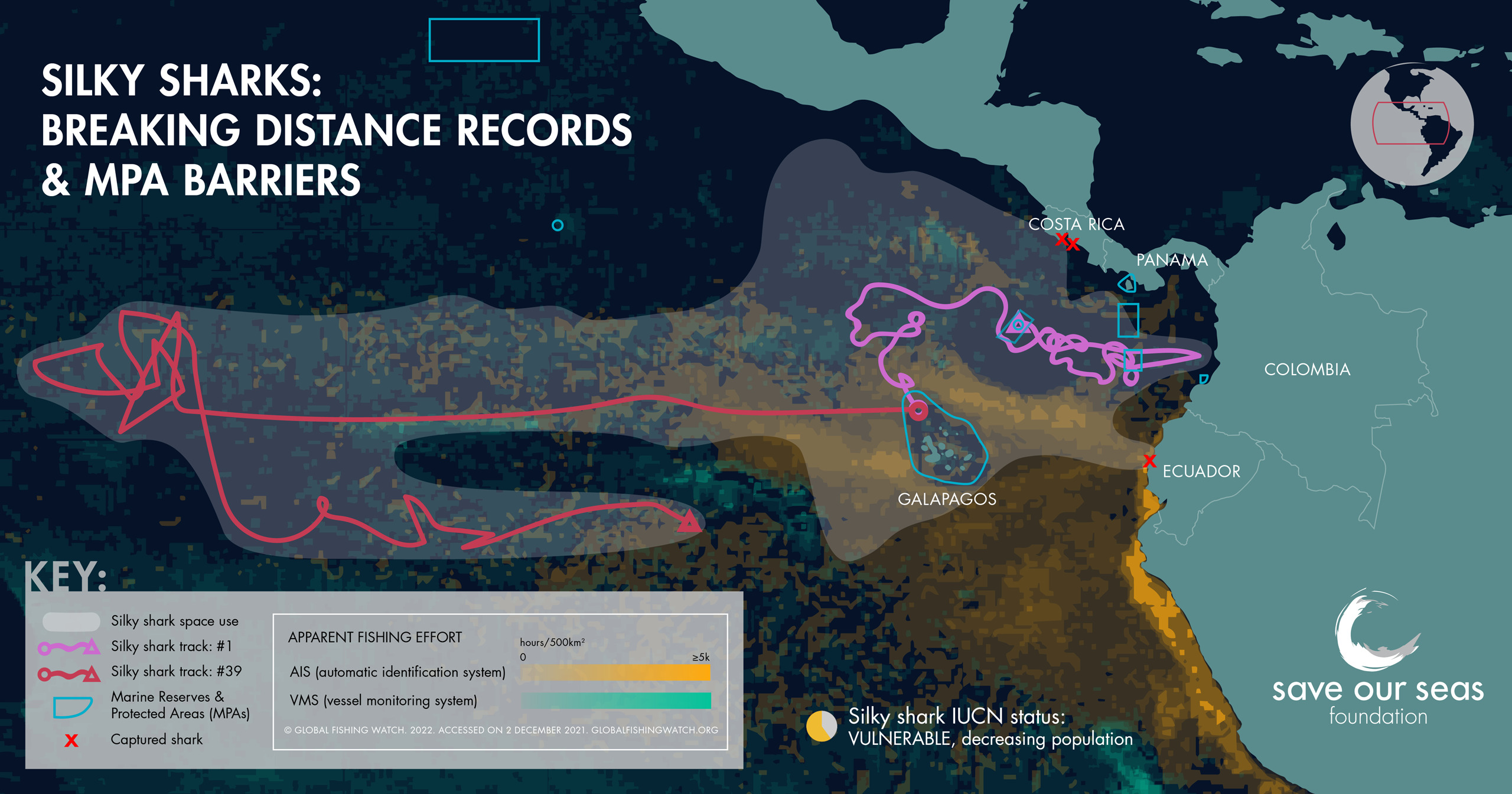

By satellite tagging and tracking silky sharks from the Galápagos Islands, a collaborative team of researchers from the Guy Harvey Research Institute and Save Our Seas Foundation Shark Research Center (SOSF SRC) at Nova Southeastern University and the Charles Darwin Foundation, with the support of the Galápagos National Park Directorate, are learning more about how silkies move across the Eastern Tropical Pacific. The movements, observed over a year so far, reveal that many individuals spend a considerable amount of time in unprotected waters during long, mysterious journeys, including some that stretched unexpectedly far west of the islands.

Photo by James Lea

‘Silky sharks don’t make headlines often, but they do deserve our attention’, says Dr Pelayo Salinas de León, a co-leader of the project who has been studying sharks in the Galápagos since 2012. Silky sharks are among the most heavily fished shark species in the Tropical Eastern Pacific ecoregion. Not only do their fins make up one of the largest proportions of the global fin trade, but their tendency to spend time on the high seas outside of the Marine Protected Areas of the region, also puts them at risk of being incidentally taken as bycatch by industrial fishing fleets.

Understanding silky shark movement patterns, says Dr Salinas de León, and comparing them with areas of high fishing activity will help us to identify where and when these animals are most vulnerable. Sharks play an essential role in keeping marine ecosystems healthy and balanced. The biggest threat to their survival is overfishing, so taking these spatial overlaps into account, he explains, is a critical step towards reducing ongoing population declines.

Artwork by Nicola Poulos | © Save Our Seas Foundation

Most of the 47 silkies tracked by the team are adult females. And yet they show two very different movement patterns, notes Prof. Mahmood Shivji, Director of the SOSF SRC and co-leader of the project. Some individuals seem to prefer waters close to home, whereas others opt to embark on exceptionally long swims. One individual, a female known as ‘Silky 39’, clocked an impressive 16,300-kilometre (10,129-mile) – and counting – jaunt west to the open ocean and back east, getting close to the Peru coast. The 10-month-long trek beats the former silky shark swim record – held by a shark in the Indian Ocean – by more than 11,500 kilometres (7,145 miles).

says Prof. Shivji.

The silky shark tracks can be followed on a publicly accessible website (select Project 22).

It’s possible that environmental factors like shifting ocean currents, which drive hotspots of tuna and other prey, are at play, but more work is needed to say with greater certainty.

While Prof. Shivji’s question remains unanswered for now, the ‘where?’ is beginning to come into focus. Over the past 12 months, Silky 39 and her fellow travellers moved far and wide. Some sharks made pit-stops at multiple marine protected areas and UNESCO World Heritage Sites across the region, including Isla del Coco National Park in Costa Rica and Malpelo Flora and Fauna Sanctuary in Colombia. However, most of the silkies also spent substantial time in unprotected areas with high fishing activity.

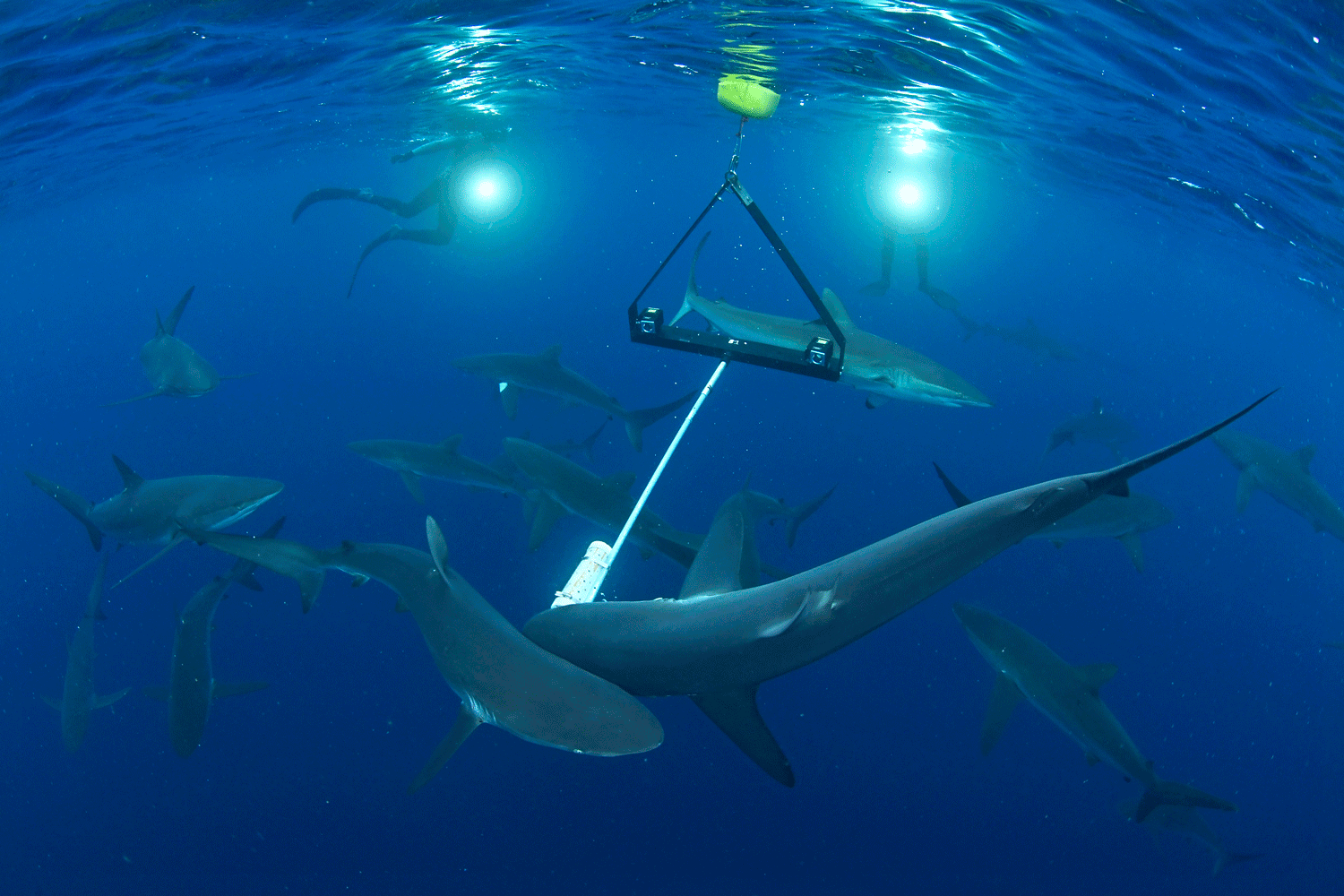

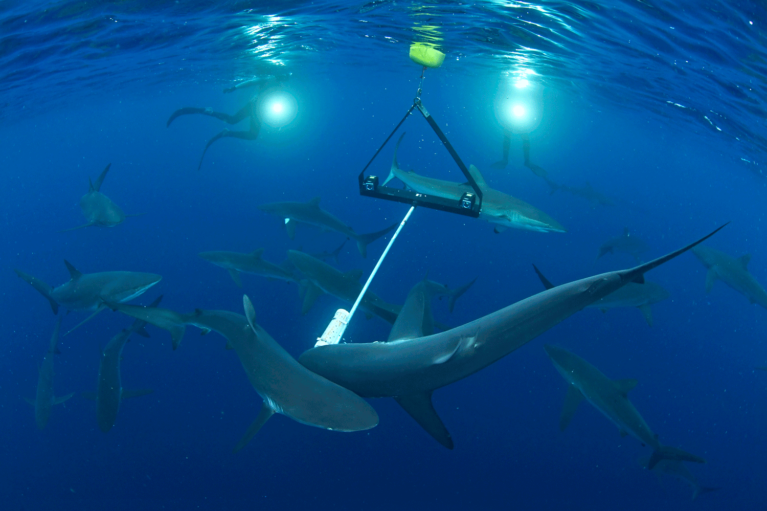

Photo © Christopher Vaughn-Jones

In March 2022, Ecuador expanded protection around the Galapagos Archipelago. The new 60,000 square kilometre Hermandad Marine Reserve increases protection around the 133,000 square kilometres Galapagos Marine Reserve, to include part of the Cocos Ridge, an underwater mountain range on the north-eastern side of the Galápagos Archipelago. Many species, including scalloped hammerheads and leatherback sea turtles, travel along the ridge to find foraging and nesting grounds. In order to better protect this region, the governments of Ecuador, Panama, Colombia and Costa Rica have announced a commitment to extend fishing restrictions between their respective countries. Together, the changes would mark the creation of an underwater wildlife corridor, a protected migrating route for animals like silky sharks that regularly move between these areas. The trouble is, some individuals in the recent study also turned up outside its borders.

‘Expanding existing protected areas and establishing new ones are definitely steps in the right direction,’ says Dr Salinas de León. ‘However, highly mobile species like sharks do not know where lines on a map are and just follow their more basic instincts to find food, reproduce or just hang out.’ ‘Marine protected areas alone’, he says, ‘will not do the trick to save threatened shark species from extinction’. ‘Ambitious and comprehensive international management tools for improved ocean governance, including fisheries, are urgently required to reduce ongoing population declines,’ he adds.