Uncovering the presence of sawfish in Colombia and Panamá

As soon as the fish took the bait, explorer Mike Hedges had lost control of the boat. Despite his best efforts, the wooden yacht was being towed by one of the strongest fishes he had ever hooked. It was 1921 and the experienced captain was on the last fishing trip of a 2-year long expedition to Panamá’s Pacific coast. Now the boat was being pulled wherever the fish pleased, around the densely forested island of Taboguilla without being able to gain control. After around 12 hours of fighting, finally, the fish showed signs of exhaustion and they were able to land it on the beach. They soon realised that the mysteriously strong fish, that Hedges had nicknamed “leviathan of the deep”, was a massive sawfish. The prehistoric-looking fish measured more than 7 metres long, and when the autopsy was performed, they found it was a pregnant female with 36 babies almost ready to be born. A couple of these foetuses were preserved and now are part of natural history museum collections in Hedges’ native Britain, and the memoirs of his trips were published in 1923 in the book ‘Battles with Giant Fish’.

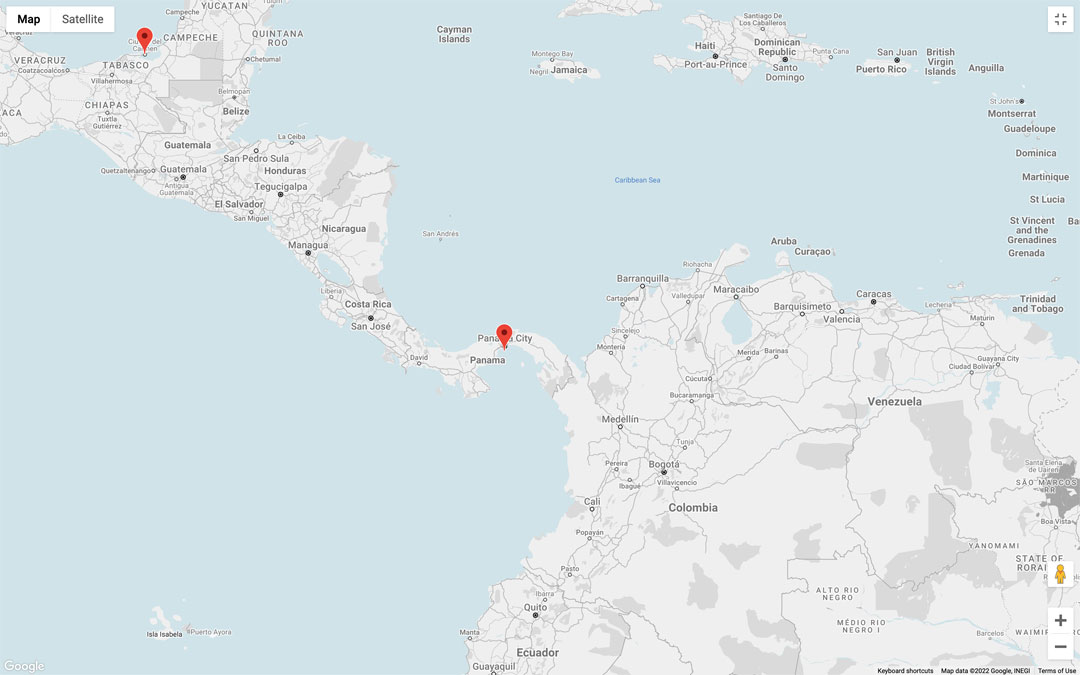

Map depicting the location of Isla Taboguilla, Panama. Map © Snazzy Maps | Google Maps.

Sawfish are mighty creatures, they attract and catch prey with their highly sensorial saw, and are incredibly strong. Fishers often recount tales of broken boats due to enormous sawfish thrashing around as they try to disentangle their saws from fishing nets. Sawfish inhabit brackish waters, and females go up rivers to give birth, so when their babies are born, like tiny versions of adults, they can easily hide in the turbid water amongst mangrove roots and avoid predators. Therefore, it is not surprising that the intrinsic fascination that attracted explorers in 1921 to the other side of the world to look for sawfish, is the same one that keeps us scientists looking for them nowadays. The big difference is that previously, it was common to find them. Now, however, in much of their original range, sawfish are only ghosts of the past. Despite sawfish being globally distributed in the tropics and subtropics, they are one of the most endangered fishes in the world, with all five extant species of sawfish listed by the IUCN as Endangered or Critically Endangered with a high risk of extinction. The largetooth sawfish (P. pristis) is the largest species of the sawfish family and is known to be locally extinct in 27 of the 75 countries where it was historically present.

(Left) Archaeozoologist and co-author Richard Cooke studies a sawfish rostrum from his office at the Smithsonian in Panamá. (Right) Picture of a sawfish rostrum taken by our team during our surveys in Darién, Panamá in 2015. Photos © Juliana López-Angarita

Colombia and Panamá are some of the countries considered as a high priority for the development of species-specific national legal protection of the largetooth sawfish. And since the historical and contemporary status of sawfish populations was largely unknown, our team at Talking Oceans set off to find more about this fish in the tropical eastern Pacific region, where much of the coast is potential sawfish habitat. Thanks to the support of Save Our Seas and other partner institutions, we travelled along most of the Pacific coast of Colombia and Panamá between 2014 and 2016 visiting small fishing villages to talk to fishers about past and recent sawfish encounters. We complemented our interviews using fisheries landings analysis and historical research to consolidate all known records of sawfish in Panamá and Colombia and map areas of potentially extant sawfish populations.

Juliana with a proud fisher showing the rostrum he keeps at his house in Chomes, Costa Rica. Photo © Juliana López-Angarita

We found that sightings of largetooth sawfish decline with time in our study area, mirroring global trends for this species. In both countries, the majority of records were dated from the 20th century, with more than 70% of all observations occurring before the year 2000. Most fishers agreed with this decline and they attributed it primarily to mangrove deforestation and overfishing. Fishers most frequently cited the increased use of gill nets as the reason for sawfish decline in shallow areas, given that the fish entangles easily with these nets. Local names for sawfish used by fish workers in Colombia and Panamá were ‘pez sierra’ (saw fish), ‘guacapa’, ‘pez espada’ (swordfish), and ‘pejapa’. In our spatial analysis of sawfish distribution, we defined ‘bright spots’ as areas that were hotspots of sawfish occurrences within the last 10yrs. Bright spots identified were as the Darién region in Panamá (Tuira River) and Northern Chocó in Colombia (Utría National Park and Golfo de Tribugá). These locations are characterised by high coverage of mangrove forests and low human population density, which coincides with similar findings by other sawfish studies in the region. In Costa Rica, Valerio-Vargas & Espinoza (2019) found sawfish remained in areas of densely protected mangrove forest, such as the Térraba-Sierpe National Wetlands. In Perú, Mendoza et al. (2017) reported them in Tumbes region in the north of the country.

Our study, published recently in the open-access journal Endangered Species Research, is the first to identify priority areas for the protection of sawfish in Colombia and Panama. However, this protection for sawfish will only be possible if interventions and regulations are established with local communities to ensure local legitimacy, enforcement, and compliance (Rohe et al. 2017) Sawfish embody the very human fascination with the unknown, and as our minds are hardwired to be inquisitive, we will continue to be captivated by this creature whose appearance seems to challenge the rules of this world. We hope our research promotes more efforts in the region to raise awareness, investigate and protect this critically endangered species.