Three years of tracking trevally – what did we find?

The BBC Blue Planet II series launched the Seychellois giant trevally to global fame. To better protect this species, scientists monitored where and why the fish roam as they grow.

In the opening episode of Blue Planet II the giant trevally of Seychelles introduced itself to the world by shooting out of the sea to snatch birds from the sky. The giant trevally, or ‘karang ledan’ as it is known in Seychelles, typically eats fish, not birds. Much like many shark species, this large fish is a key predator, critical for maintaining healthy balanced reef ecosystems. ‘The giant trevally is a popular, sought-after prize fish in Seychelles, particularly in the big game sport fishing industry. Seychelles has a reputation for being one of the best trevally destinations in the world. The species is also caught in the handline fishery,’ explains Helena Sims, the Save Our Seas Foundation’s (SOSF) Seychelles ambassador. Sims was part of the marine spatial planning (MSP) initiative determining what 30% of Seychelles waters should become marine protection areas (MPAs) and has more than a decade of conservation experience.

New research reveals how to improve the sustainability of giant trevally fishing

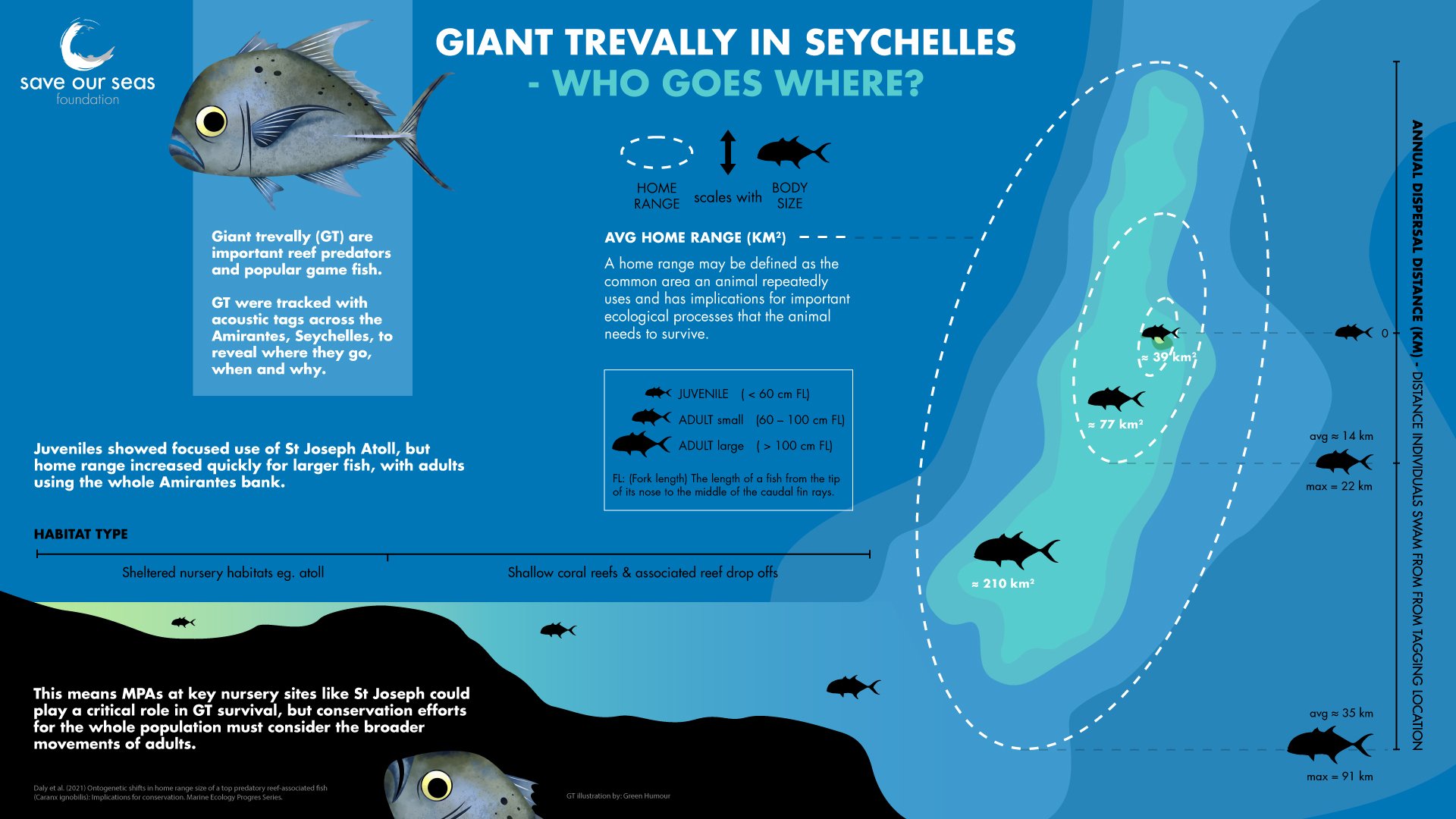

‘Although the giant trevally is very popular and sought after, not much was known about its population dynamics in Seychelles until recently,’ Sims explains. Fishing enthusiasts come to Seychelles from all over the world to catch giant trevally. New research by the Save Our Seas Foundation D’Arros Research Centre (SOSF-DRC) provides recommendations to help ensure that fishing for the species in Seychelles remains sustainable by suggesting which areas to prioritise for protection. The research has revealed that to protect giant trevally throughout their lifespan, the nursery areas of this iconic predator, which are critical habitats for the survival of the next generation, should be conserved. In addition, the larger areas these fish move through and frequently use as adults should be taken into account when conservation planning is undertaken.

Following fish

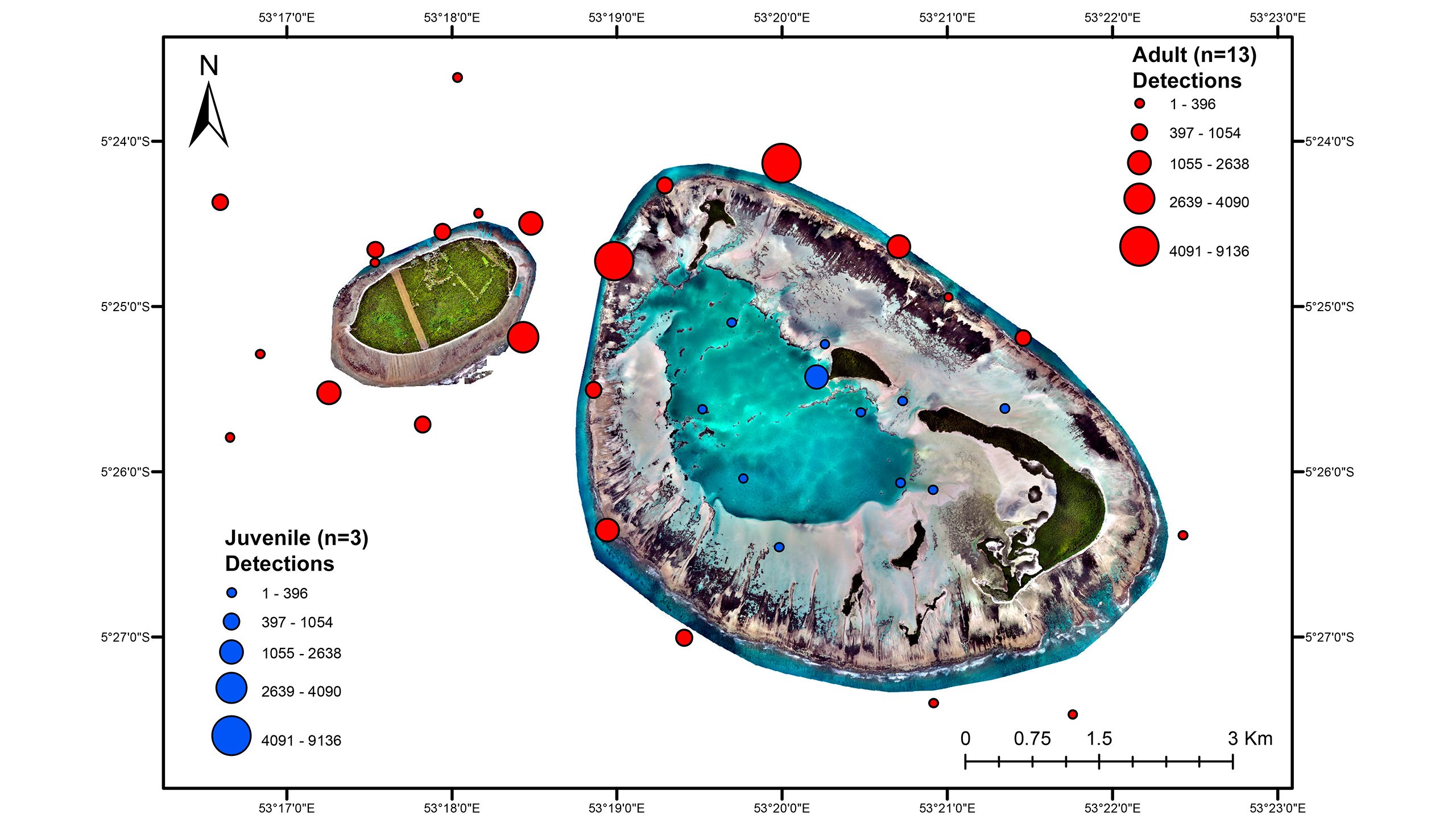

In 2016, to find out where giant trevally went in the Amirantes island group, as well as when and why, a number of individual fish were fitted with acoustic tags. Their positions were tracked by the SOSF-DRC’s network of 88 acoustic receivers, which are positioned around St Joseph Atoll, D’Arros Island and all the rest of the Amirantes. This receiver network is the only one of its size and kind in the Amirantes and for more than three years it tracked some of the tagged giant trevally as they moved through these waters.

What did the research find?

The research revealed that juvenile giant trevally stayed around St Joseph Atoll, although the extent of the area they frequently used increased quickly as they grew bigger. By the time the fish were adults, they were using the whole Amirantes Bank. Although small and large adults used similar areas, large adults sometimes travelled longer distances, probably driven by their growing appetites as they needed to eat more and more food to sustain their increasing body size. Both the reduced risk of predation on account of their increased body size and the onset of sexual maturity appear to be linked to them using a larger area and a wider diversity of habitats.

This study showed that the area giant trevally frequently used was larger than had been reported from other tropical islands and atolls around the world. Dr Ryan Daly, a former director of the SOSF-DRC, explains that the study showed that ‘it took some giant trevally a surprisingly long time – on average 18 months but sometimes more than 30 – to use the full extent of their home range. This emphasises the need to follow, track and monitor threatened species in the marine environment for long enough to appreciate the full extent of their home ranges and thus to understand how spatial protection like MPAs is going to be effective.’ Daly led the research, which was published as ‘Ontogenic shifts in home range size of a top predatory reef-associated fish (Caranx ignobilis): Implications for conservation in Marine Ecology Progress Series on 15 April 2021. This study provides insight useful for marine spatial planning in Seychelles.

This year Seychelles will achieve the 2030 international marine protection targets

Seychelles is leaps and bounds ahead of most countries in terms of meeting marine protection targets. Scientists have called for 30% of the ocean to be MPAs by 2030 and governments of Parties to the UN Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD) may soon agree to this target when CoP-15 is held in Kunming, China, in October this year. While the rest of the world is still to agree and commit to this target, Seychelles last year released the final details of a network of MPAs that increases the percentage of its protected waters from 0.04 to 30%. Implementing these MPAs is set to begin this year. As part of the 30% set to become protected, the Seychelles government has incorporated the entire Amirantes Bank, including St Joseph Atoll, into part of a larger Zone 2 MPA.

How does this study contribute to marine spatial planning?

Daly recommends that St Joseph Atoll’s Zone 2 status should not allow fishing of giant trevally because the area is a refuge for the next generation. If fishing is to be allowed at the atoll, he advises that it should only be catch-and-release. He suggests the areas that the adults commonly use and occasionally move through, as revealed by this study, should also be considered when further marine spatial planning is carried out in the region. Daly explains that it will be important to find a balance between harvesting giant trevally as a food source and high-value giant trevally catch-and-release fishing. He encourages this form of fishing for the trevally, but stresses that regardless of the balance chosen, it is important to protect nursery areas like St Joseph Atoll so that giant trevally fishing is sustainable.

Going forward

Sims explains, ‘For Seychelles, it is important to study the ranges of targeted species to better understand how to manage and conserve them effectively. It is very positive to see a push for catch-and-release fishing through the efforts of local associations, such as the Seychelles sportfishing club and others. It will be better yet to see increases in catch-tag-and-release fishing. Equally important, however, are studies on survival rates post-catch-and-release.’ She adds, ‘We need such sound science to inform key policy and management decisions for these species not only to ensure ecological sustainability but also to protect local livelihoods and provide financial security to local businesses in the long term.’