Stay home, stay safe

Although tiny specks in the Indian Ocean, D’Arros Island and St Joseph Atoll are home to a dazzling community of species. In March 2020, as the world took shelter from Covid-19, Seychelles declared a phased marine protected area around them.

As I write this, I’m at home. And for much of 2020, and it’s looking like 2021 as well, home has been everything. It’s the office, the gym, it’s where I go for happy hour and team calls. I’m guessing you’re at home too, and if not, are heading back there soon. For many of us, the past year pushed us to both appreciate and lament aspects of home we’d never considered before: the arc of the sun travelling across the kitchen table, the thinness of the walls.

Staying put is not modern human behaviour. It’s uncomfortable. Our cultures are set up around movement and we largely associate freedom with mobility: trips to the grocery store, site visits, long weekends away, visiting family across town or on the other side of the world. By and large, these things didn’t happen in 2020. Today, immobility is a singular experience, shared worldwide. Wherever you were in March 2020, geographically, you’re probably still there now. Cumulatively, how many miles or kilometres have you travelled since then? I’d bet it’s a small number. Despite the trauma, the upheaval, the uncertainty of 2020, we’re all stuck together, individually, at home.

But staying put is natural behaviour for much of the animal world. Although not specifically stated, a large part of the mission of the Save Our Seas Foundation D’Arros Research Centre (SOSF-DRC) is to understand what home means to the myriad of life on and around the island and neighbouring atoll, St Joseph. Are D’Arros and St Joseph a childhood home, a nursery where a species is born and raised until heading for deeper waters in adolescence or adulthood? Are their reefs and lagoon a seasonal getaway, a place to visit when the winds shift, or to start a new generation? Or maybe they’re a permanent residence? Is a fish’s home a single reef or does home stretch across the wider Amirantes Bank?

In a way, 2020 tapped the latent scientist within each of us, waking us to observe movement patterns in our own lives, across space and time, as what was once normal is now disrupted and interrogated and unclear. In the language of scientists and peer-reviewed journals, the year has drawn our attention to our own site fidelity, home ranges and spatial and temporal patterns. If you have travelled since March 2020 beyond your own well-defined home range, perhaps you feel a bit like a study subject, with officials and family alike wanting to know where exactly have you been and for exactly how long. Were you safe? What precautions were in place?

When working to protect species around D’Arros and St Joseph, many of which are threatened at various levels of extinction, these are exactly the questions we ask. And these questions are essential for the conservation of both migratory species that cross oceans and homebodies that maybe consider home to be a dark cave on a reef wall. It is our responsibility to understand what home means, what it takes for a fish to be safe at home.

Photo © Daniel Beecham

MARINE PROTECTED AREAS: A FISH’S REEF IS ITS CASTLE

This is where the mission of SOSF-DRC comes into play; the research centre’s core priority is to achieve and maintain protection for the marine ecosystems and life surrounding D’Arros Island and St Joseph Atoll. Behind every research project is the drive to ensure that when the animals of D’Arros and St Joseph return from a long absence or flow through yet another tidal cycle in their birthplace, they are safe.

Stay home, stay safe. The idea that home is a safe place, a place of sanctuary, is both a legal and a cultural part of modern life and dates at least as far back as the Romans. Castle doctrines, based on British jurist Sir Edward Coke’s 1604 dictum ‘Every man’s house is his safest refuge; every man’s house is his castle’, are common sense to many. Yet this is not true in the natural world. Every fish’s crevice is not its castle, every fish’s reef is not its safest refuge. In fact, the opposite is more often true. A fish’s home is where the fisherman goes.

Marine protected areas (MPAs) are best practice for creating refuges and sanctuaries for marine animals and protecting ecosystems and habitats, the castles of the sea. Understanding home ranges, site fidelity and the spatial and temporal considerations of home is particularly important when designing and delineating these protected areas. How else are decisions made about what’s protected and what’s not? What do the boundaries encompass, whose home and what part of that home is protected? Importantly, do the protected area boundaries create a sanctuary that is equivalent to a safe living room, but where heading to the kitchen is a risk?

Photo © Byron Dilkes.

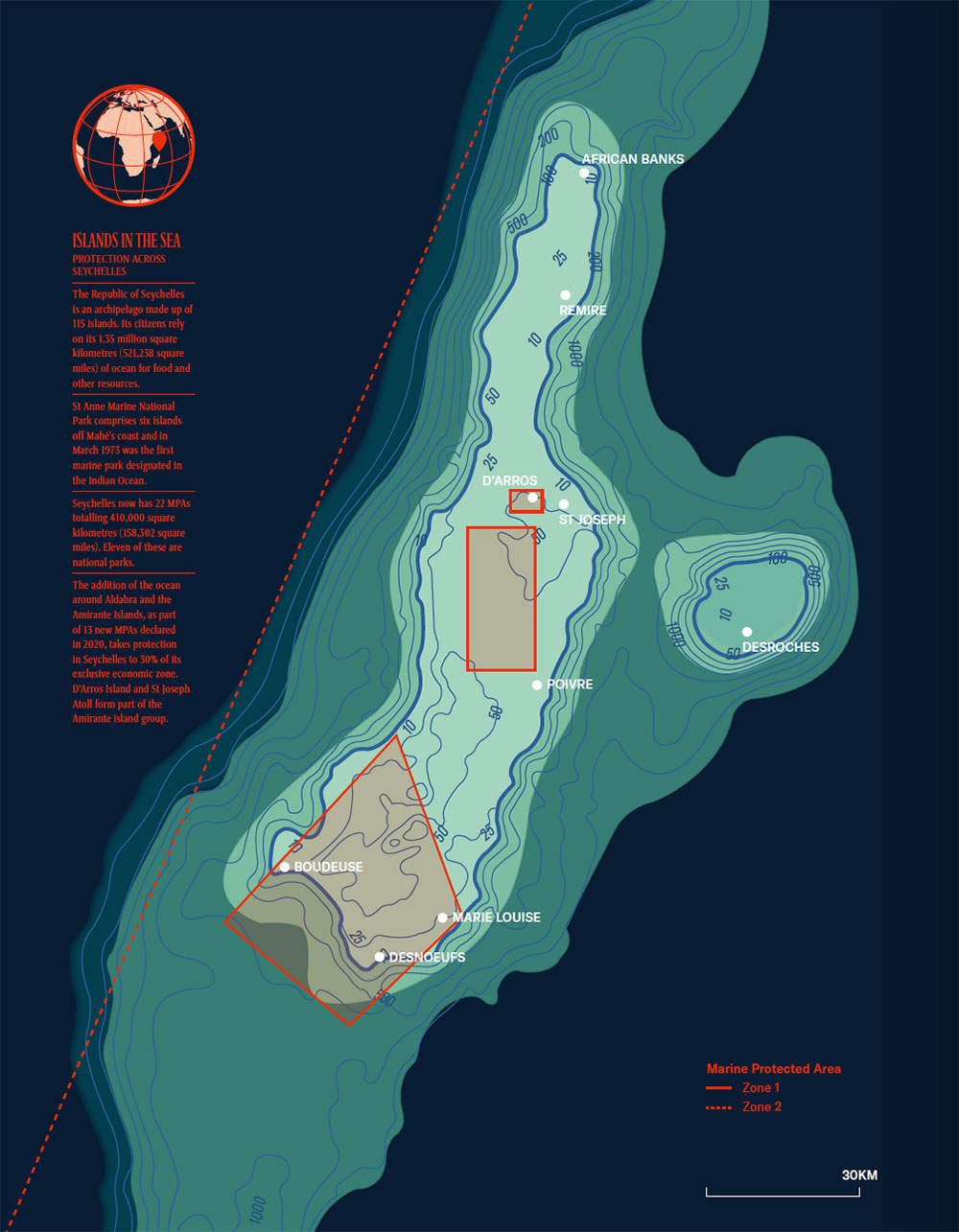

As a nation, Seychelles understands the importance of protecting the marine realm on which its economy and people rely. In March 2020, when much of the world was beginning to ‘shelter in place’, its government committed to sheltering a third of the ocean nation’s territorial waters – 400,000 square kilometres (154,000 square miles) – in MPAs. That’s nearly the size of California and twice the size of Great Britain. In every way, the decree that created 13 new MPAs in Seychelles is an enormous commitment to safeguarding the ecosystems and habitats that a staggering diversity of species call home.

Years of focused research and education initiatives of the SOSF-DRC, working in close collaboration with the Seychelles government, have resulted in the inclusion of D’Arros Island and St Joseph Atoll in the larger Seychelles MPA decree. The MPAs are driven to protect whole ecosystems, not just the living room, for multiple marine animals around D’Arros and St Joseph, including 15 species classified by the IUCN as Vulnerable or Endangered. This is largely because the SOSF-DRC’s extensive research and outreach have led to an understanding of the region’s critical importance as a sanctuary for countless species and habitats. The MPA declarations are like a castle doctrine for the ocean, making sure that home is a safe place for its residents.

‘The MPAs are driven

to protect whole ecosystems

for marine animals.’

NO PLACE LIKE IT: CALLING D’ARROS AND ST JOSEPH HOME

There are species that pass by D’Arros and St Joseph that we’ll never know about. When I lived on D’Arros, we had the unprecedented experience of watching a blue whale steam past the island. After years of wondering, we also finally confirmed that tiger sharks occur off D’Arros, although they remain elusive today. There are the wedge-tailed shearwaters and green and hawksbill turtles that return generation after generation to lay their eggs on the beaches and sandy soils of the island and atoll.

SHARKS: THIS MUST BE THE PLACE

St Joseph Atoll is a critically important nursery habitat for two shark species, the blacktip reef and sicklefin lemon. Scientifically, a shark nursery is defined in space and time. First, it must be an area within which pups stay for an extended period of time. Ornella Weideli’s multi-year PhD study on shark pups found that the majority of recaptured blacktip reef and sicklefin lemon sharks were found within 500 metres (1,640 feet) of their original capture location.

Second, a shark nursery must contain multiple generations of young sharks, that is, sharks that stay in the area over an extended period of time. Ornella’s study didn’t just recapture sharks in the same season; some sharks were caught and released over multiple years, meaning that the sharks live out what is equivalent to their childhood years calling St Joseph Atoll home. And then there are the homebodies of D’Arros and St Joseph, the species whose lives are governed by the ebb and flow of the atoll tides and that mark their years by the shifts the monsoons bring to their reef and lagoon homes. These are the species that stay home and now, with the MPA declarations, stay safe in the waters of D’Arros and St Joseph.

Another aspect of Ornella’s study found that these shark pups have a unique advantage over their cousins in other parts of the world. In St Joseph Atoll they benefit from the abundance of food the atoll provides, illustrating how important the protection of a species’ entire home is for successful growth into adulthood. Protect the place and the species within it will thrive. The near-pristine nature of St Joseph Atoll provides a fine-scale, spatially explicit opportunity for the meaningful protection of shark pups – and the MPAs make the most of it.

But blacktip reef and sicklefin lemon shark pups share the same space for more than brief moments of early life. The long-term research of the SOSF’s CEO James Lea on sharks across the Amirantes Islands has shown that these two species probably call the lagoon and coastal reef habitats home for their entire lives. Again, while the declaration of MPAs around D’Arros and St Joseph was not a call for shelter in place, many species already use the area as a sanctuary. The declaration means that these sharks’ home is safe.

Photo © James Lea

HUMPHEAD WRASSE: OH, THE PLACES YOU’LL STAY

In the December 2018 issue of this magazine, I described efforts to acoustically tag 20 humphead wrasse. That 2018 SOSF-DRC survey remains globally the largest study of this charismatic but Endangered and conservation-dependent species – and for me personally one of the most fun research experiences ever. At the time of writing that article, we were awaiting results from the study, but field work had already determined that Seychelles, specifically the channel between D’Arros Island and St Joseph Atoll, may be home to the highest known densities of this species in the world. For an underappreciated species and one whose global decline is being driven primarily by its delicacy status in the live food fish trade, the difference between conservation success or failure in Seychelles may rest on a clear definition of what home means to this population.

Consider the humphead wrasse a homebody. It appears to call the dark caves along the reef wall of the channel home, rarely venturing far during daylight hours and returning to the same cave at the end of each day. Over a period of nearly 500 days, not one of the 20 tagged individuals was recorded beyond a one-kilometre (1,093-yard) radius of D’Arros and St Joseph. Remember that number of miles or kilometres of travel from home you calculated earlier? I bet it was more than a humphead wrasse’s cumulative movement over a 500-day period – and that’s without travel restrictions. Humphead wrasse are model shelter-inplace practitioners, which in part makes protecting their immediate habitat easier.

If they stay in one place, make sure that place is as safe as can be. The new MPAs ensure that these humphead wrasses’ home is their safest refuge.

Humphead wrasses mature late, change sex and live for up to 30 years, traits that make them vulnerable to overfishing. They are classified as Endangered. Photo: Gregory Piper

Photo © Dan Beecham

REEF MANTA RAYS: HAVE WINGS, WON’T TRAVEL

For four years the PhD study of SOSF-DRC researcher Lauren Peel tracked acoustically and via satellite reef manta rays around the Amirante Islands of Seychelles and built up a photo-ID database of individuals known to frequent the popular manta cleaning station off D’Arros. Were the manta rays merely stopping over as they moved through the territorial waters of Seychelles?

Understanding where these manta rays travel to, and where they stay, is an important conservation strategy for a species that faces global population declines based on its market value in the Eastern traditional medicine trade. Lauren suspected that juvenile reef manta rays may stick around D’Arros and St Joseph more than adults and that there may be differences between male and female habits over space and time around the island and atoll. But the mantas gave surprising results over the four-year period: 89 per cent of all acoustic detections were within 2.5 kilometres (1.5 miles) of D’Arros and St Joseph, and tagged mantas were present 64 per cent of the days they were tracked, the equivalent of four and a half days a week. That rate well exceeds the minimum length of stay many countries require for a foreigner to claim residency. The manta rays are not just passing by; D’Arros and St Joseph are home.

PORCUPINE RAYS: WHEN THE GOING GETS TOUGH, STAY HOME

It’s a purely subjective opinion, but the porcupine ray is in tight competition with the humphead wrasse as the most charismatic study subject in the history of SOSF-DRC research. This staunch species is barbless, meaning that the capture method for Chantal Elston’s PhD work on it entailed a gloved rodeo-style approach that rewarded stealth but, like handling anything spiky, required respect. As in the case of the humphead wrasse, it’s possible that the porcupine ray population around D’Arros and St Joseph is one of the densest in the world. Understanding what habitats the porcupine ray calls home is, as for any Vulnerable species, a global conservation concern. Chantal’s study monitored porcupine rays over two and a half years and determined that they too stay within what are now the boundaries of the newly declared MPAs. In particular, the majority of tagged porcupine rays were detected within St Joseph Atoll for close to or more than a year, once again highlighting the benefits that would accrue if the atoll were to be designated a multi-species sanctuary.

Photo by Rainer von Brandis | © Save Our Seas Foundation

Photo © Dan Beecham

A NATION’S BLUE HEART

Perhaps most importantly, Seychelles is home to people who care deeply about the ocean now and for generations to come. It is because of these people, and the visionary actions of the Seychelles government, that D’Arros Island and St Joseph Atoll can act as a sanctuary home to so many important marine species. Uncertainty still lies ahead – external factors like climate change will increasingly impact ocean ecosystems – but taking the steps now to protect near-pristine and critical habitats like those declared as MPAs in Seychelles is an essential step towards ensuring best-possible outcomes for conservation in the future.