Sobering results from a first survey of Ghana’s sharks and rays

‘To my surprise, there was absolutely no information about Ghana’s elasmobranchs and very little about sharks and rays generally in West Africa,’ says Issah Seidu, a Save Our Seas Foundation (SOSF) project leader and a PhD candidate at Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology. His enthusiasm for his work and his passion for sharks and rays are evident in his prompt response to our interview. Swamped somewhere between the frenzy of grant application deadlines and the pressure of conducting ongoing field work, Issah finds a gap to highlight for us some of the key findings he wants the world to know about from his latest published article.

he explains. ‘We recorded a total of 20 shark and 14 ray species in the study. Of these, 18 sharks and seven rays are threatened with extinction, classified as Critically Endangered, Endangered or Vulnerable on the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species.’ The findings are sobering and point to a critical need for intervention and protection for sharks and rays in Ghanaian waters. ‘The study sheds light on Ghana’s artisanal elasmobranch fisheries and provides baseline data,’ says Issah. ‘This information is indispensable for future monitoring efforts and for devising sustainable management strategies for Ghana’s sharks and rays.’

Issah is something of a late bloomer when it comes to shark conservation. Although he was initially unnerved by their fearsome reputation, his perception changed when he witnessed at first hand how vulnerable sharks and rays are to human activities. ‘I was motivated to study sharks and rays in July 2016 while I was on holiday in Dixcove, where the local fishers target mostly sharks to earn their livelihoods. The increasing rate at which sharks were targeted and landed, with no thought of conservation, and the horrifying scenes of them being butchered at the landing sites sparked my curiosity to launch a pilot study on them.’

Landed canoes at Dixcove. Photo © Issah Seidu

Since then, Issah has founded Aqualife Conservancy, an NGO that focuses efforts to conserve Ghana’s freshwater and marine biodiversity. A project fellow of the EDGE of Existence programme, he believes wholeheartedly in understanding more about sharks and rays to better manage and protect them. ‘There is much to study about Ghanaian elasmobranchs. I want to help fill this knowledge gap and make sure these species are sustainably managed by conducting groundbreaking baseline studies and building local capacity to support my conservation efforts.’

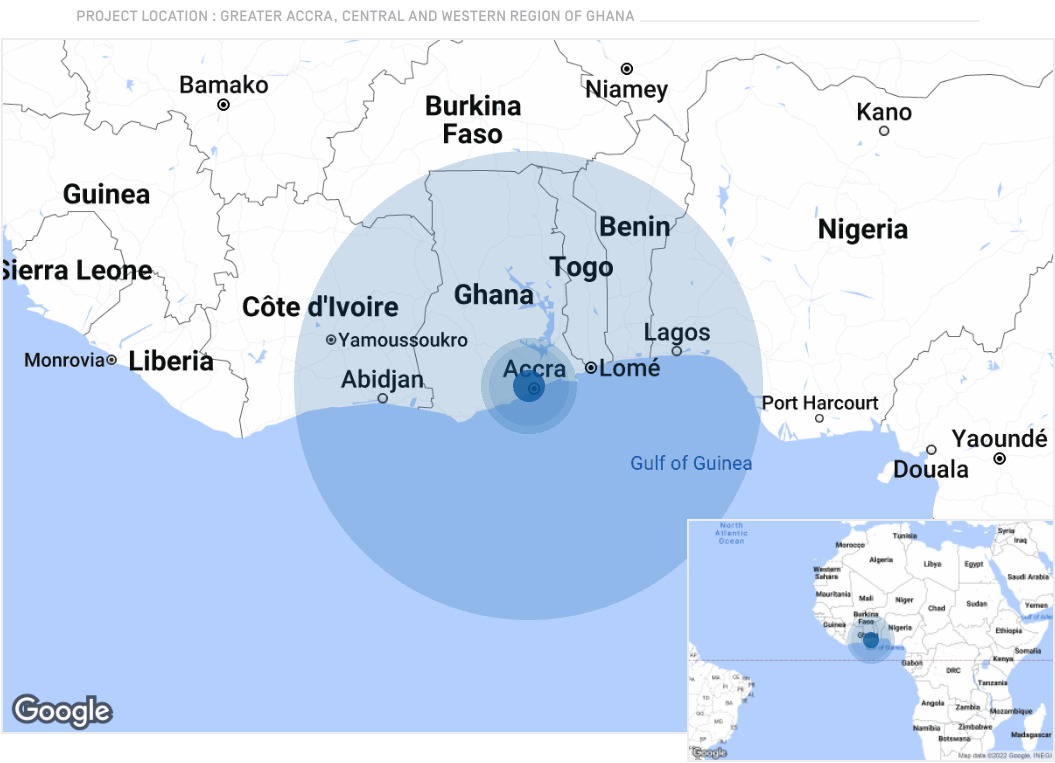

The article ‘Species composition, seasonality and biological characteristics of Western Ghana’s elasmobranch fishery’ was published in Regional Studies in Marine Science in March 2022. Issah and a group of trained local volunteers surveyed the catches at landing sites in five artisanal fishing communities in Western Ghana: Adjoa, Axim, Busua, Dixcove and Shama. The project was not without its challenges. ‘In the beginning,’ recounts Issah, ‘team members were molested and in some fishing communities our cameras were seized. The fishers and canoe owners were very hostile towards us because it is well known that there is controversy – globally speaking – surrounding shark and ray population declines.’

The fishers were antagonistic at first, but Issah’s team still needed to get information from them to piece together a picture of the diversity of sharks and rays caught at different sites and at different times of the year in Western Ghana. ‘Most of the fishers were suspicious of our activities because they believed we were collecting information that could be used against them. These challenges stalled our project for months.’ It was time for a collective re-think. ‘So we organised a series of meetings in small groups and had discussions with the fishers about the rationale and objectives of the study. Doing this gave us an opportunity to build their trust in us.’ It seemed that the problem was solved, but from time to time Issah still encounters a resurgence of these challenges in his work. ‘Even after all these discussions, occasionally we still run into a pocket of hostility from some of the fishers who are operating illegally. These situations delay our progress in the field because we have to halt our work and develop new strategies to approach the fishers whenever they attack us.’

Project leader Issah Seidu measuring a blackchin guitarfish at Apam community.

Issah found that the blue shark and the African brown skate dominated catches; that shark catches were highest in Shama and ray catches were highest in Axim; and that catch numbers and species richness were highest between August and November, Ghana’s minor rainy season. ‘It was surprising that many sharks and rays are targeted and landed without any thought of conservation, even though they are species that are listed on Appendix I of CMS (the Convention on the Conservation of Migratory Species of Wild Animals) and Appendix II of CITES (the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species),’ he says.

Issah’s work highlights the disconnect between international agreements and the on-the-ground reality of shark and ray landings, where there are challenges to enforcement and conservation management. ‘For example,’ he explains, ‘species such as the ragged-tooth and oceanic whitetip sharks and the sicklefin and bentfin devil rays are all listed on Appendix I of CMS. Considering that Ghana is a signatory to this convention, these species should have received strict protection in this country. And all these species, as well as the big-eye and common thresher sharks, the blackchin guitarfish, the shortfin mako shark and the scalloped and great hammerhead sharks, are listed on CITES Appendix II. International trade is restricted on these species. However, these international conventions are poorly implemented.’ He continues, ‘I doubt whether fishers and traders are even aware of the conventions protecting these species, or aware enough to warrant their strict implementation in Ghana.’

Community members waiting for the catch from the canoes. Photo © Issah Seidu

But Issah remains hopeful, despite the disconcerting findings.

Moreover, his work will continue. ‘Our immediate next step for the project is three-fold,’ says Issah. ‘First, our study has given us an understanding of the complex dynamics of shark and ray fisheries in Western Ghana. When the project began, we anticipated that migrant fishers were not actively involved in shark and guitarfish fisheries. However, over its course we established that migrant fishers from the Dogo and part of Manford communities in Central Region have specialised gill nets that are used mostly to target large rhino rays. We therefore plan to talk with these migrant fishers to understand their fisheries, their motivation and their migration routes, as well as the areas where they mostly target these large, shark-like rays. It is critical that we do this so that policy measures can be drawn up quickly based on this information and put in place across Ghana and in neighbouring countries.’

The timing of Issah’s findings is crucial to the conservation of some of the most threatened elasmobranchs in the ocean. But finding a way forward for the fishers whose livelihoods depend on healthy elasmobranch populations is also on the radar. ‘We hope, as a second step, to discuss and pilot alternative livelihood strategies for some fishers who now target sharks and rays. We will discuss these livelihood options further with both resident and migrant fishers before we implement them.’

Finally, Issah’s vision is to make his science relevant to policy and to influence positively the direction of shark and ray conservation in Ghana. ‘We have gathered substantial baseline data on sharks and rays in Western Ghana and are hoping to extend our efforts into equally important coastal fishing communities along the country’s central and eastern coasts. We can gather holistic information about sharks and rays and liaise with governmental organisations like the Ministry of Fisheries and Aquaculture and the Fisheries Commission of Ghana to develop legislative instruments to protect some of the species of sharks and rays that are most at risk.’

The community of Axim. Photo © Issah Seidu

Publication available online here.

**Reference: Issah Seidu, David van Beuningen, Lawrence K. Brobbey, Emmanuel Danquah, Samuel K. Oppong, Bernard Séret.