Scientists create a ray of hope for Critically Endangered species, despite ongoing trade

Scientists have assessed how the 2019 CITES Appendix II listing of highly threatened wedgefish and giant guitarfish affected the international trade in these species. Worryingly, their prevalence in the Hong Kong fin market has remained at pre-CITES listing levels. But the researchers also developed a fast and cheap PCR (genetic) test for border control officials to detect endangered rays in shipments that lack CITES permits. Their work has identified the sites where illegal trade can be intercepted most effectively.

We’re right to worry about wedgefish (family Rhinidae) and giant guitarfish (family Glaucostegidae), those slow-growing rays with their coveted shark-like fins. They are among the most threatened sharks and rays on earth, and recent re-assessments have classified all but one of the 18 species in these families as Critically Endangered. And, according to a new study by Demian Chapman and co-authors, the international trade in the fins of these highly threatened rays is ongoing, despite regulations that come from their 2019 listing on CITES (the Convention on International Trade of Endangered Species of Wild Flora and Fauna) Appendix II. The high value of their fins encourages fishers to retain these animals rather than release them, even where they are caught as bycatch. To prevent their extinction, it is critical that the international trade in these species is regulated.

Artwork by Kelsey Dickson | © Save Our Seas Foundation

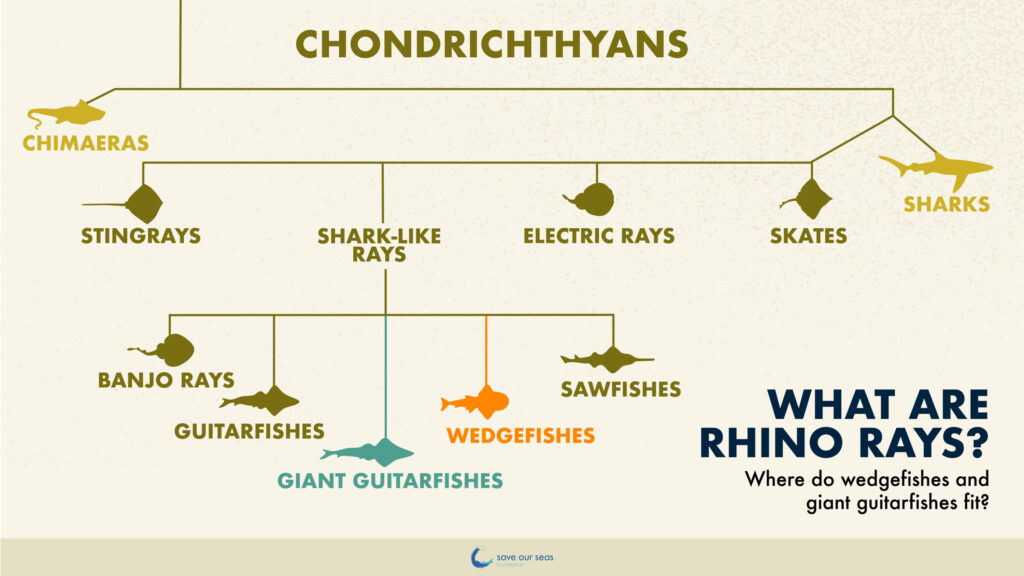

What are the shark-like, or 'rhino' rays?

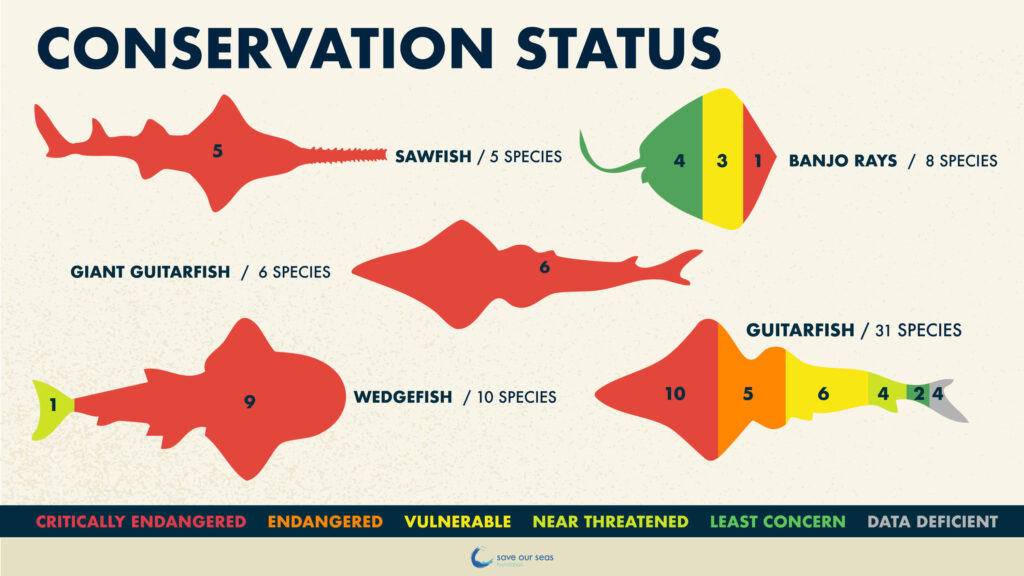

With bodies flattened to suit a life on the seabed, shark-like rays comprise 62 species across five families: sawfish, wedgefish, giant guitarfish, guitarfish and banjo rays. All the sawfish species are Critically Endangered and listed on CITES Appendix I, which prohibits any international trade in sawfish-related products. The wedgefish, giant guitarfish and guitarfish species are also considered to be the most threatened in all the shark and ray families. All species in this group are slow-growing and slow to mature, have low birth rates and are therefore incredibly vulnerable to overexploitation. The term ‘shark-like’ comes from the pronounced fins that are common to the species in the group.

Artwork by Kelsey Dickson | © Save Our Seas Foundation

Why are these species at threat of extinction?

Artwork by Kelsey Dickson | © Save Our Seas Foundation

According to CITES, the shark-like rays have been ‘quietly overfished for decades’. Many of these species are caught as bycatch or in multi-species fisheries and they are retained because their fins are highly valuable for shark-fin soup in South-East Asia. Most of them occur in the tropics and subtropics and inhabit shallow coastal waters, where they are easily accessible to fishers. In fact, these rays fetch the highest prices and occupy the most valuable category of the fin trade – the premium ‘Qun’ or ‘Qun Chi’ category. Since unsustainable levels of international trade have caused them to be overfished, in 2019 all wedgefish and giant guitarfish species were listed on CITES Appendix II. This means that, since 2020, any export of their products (like fins) has had to be certified as legal, traceable and sustainable by the exporting country.

What did this study do?

Scientists wanted to know how the 2019 CITES Appendix II listing of all wedgefish and giant guitarfish species affected their prevalence in international trade. They compared how often the species turned up in the Hong Kong fin market before the CITES listing (2014–2019) and after it (2020–2021).

They also developed a polymerase chain reaction or PCR (genetic) test that could be a cost-effective and time-efficient tool that would enable border officials of importing nations to detect these rays’ fins where they are mixed in ‘shark fin’ shipments that lack CITES documents.

And what did they find?

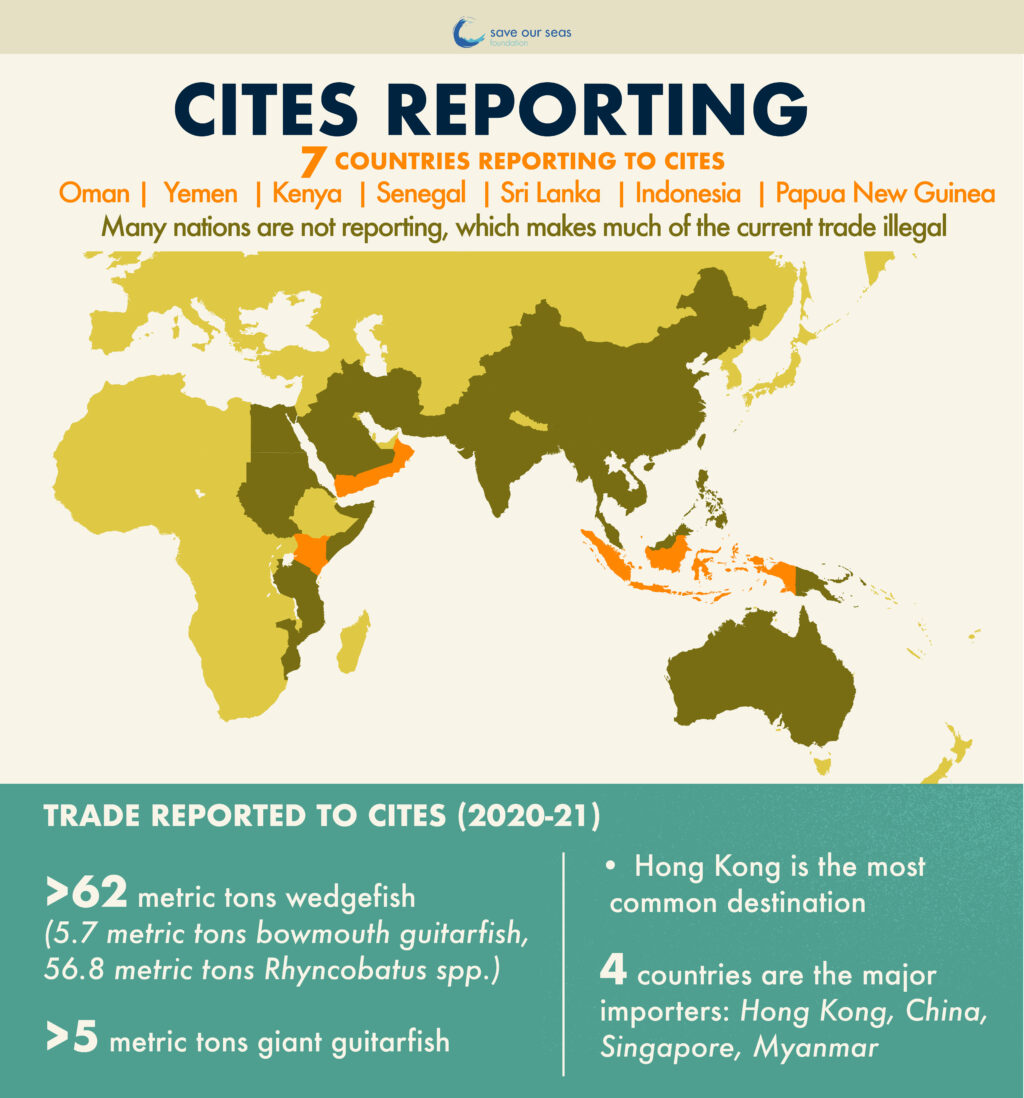

The study ‘Ongoing trade of fins from critically endangered rays (wedgefish and giant guitarfish) despite international regulations and a novel PCR test to detect rays among ‘shark fins’ was published in the journal Conservation Genetics. The researchers showed that the frequency of trade in wedgefish and giant guitarfish remained at pre-CITES listing levels throughout the study period. In fact, the trade in these species was substantial: more than 62 000 kilograms (136 700 pounds) of wedgefish fins and over 5000 kilograms (11 000 pounds) of giant guitarfish fins were reported to CITES in 2020 and 2021. The most common destination was Hong Kong.

Landing wedgefish and giant guitarfish is legal in many places. A CITES Appendix II listing only makes it illegal if the resultant products (like fins) are traded internationally without the requisite CITES export permits.

Artwork by Kelsey Dickson | © Save Our Seas Foundation

Artwork by Kelsey Dickson | © Save Our Seas Foundation

A positive sign of improved regulation as required by CITES is that the legal trade of these species was reported by some nations – notably Yemen and Oman, Kenya and Senegal, Sri Lanka and Indonesia, and Papua New Guinea – during the study period. However, most countries are not supplying a Non-Detriment Finding (NDF), which is a requirement to scientifically pledge that the continued trade from that nation is sustainable (only Indonesia had a publicly available NDF). Grounds for trade by even those countries that are supplying an NDF are questionable, given that all species are Critically Endangered (and therefore, by definition, trade in them is simply no longer sustainable at any level). It is also highly likely that there are many more range states (those fishing nations where the relevant species occur) that are simply not reporting at all to CITES and are therefore trading illegally.

But where’s the ray of hope here?

Artwork by Kelsey Dickson | © Save Our Seas Foundation

Unlike several shark species, wedgefish and giant guitarfish species can still breathe when caught in nets and lines. This means that they are typically alive when caught and could be released.

A business-as-usual approach would mean managing domestic fishing in the exporting nations whether they are reporting legal trade or not. This would involve a significant effort to monitor and manage not only the fisheries, but also the trade in these species all along the supply chain. This is still something that could – and should – happen, but the researchers suggest that there is a solution that could be more effective and also reduce the immediate burden on fishing nations, many of which lack capacity for the data collection, monitoring and enforcement required to comply with CITES regulations.

By properly regulating trade at the borders of international trade hubs, it may be possible to discourage the retention of wedgefish and giant guitarfish at source. This is because there are relatively few trade hubs in South-East Asia: notably, Hong Kong, China, Singapore, Thailand and Myanmar. These countries often have more capacity than fishing nations to intercept illegal shipments of dried fins, and they have clear legal authority to enforce CITES regulations as products arrive at their borders.

To this end, there have also been some very positive strides. Hong Kong – the dominant importer of legal fins and a recipient of shipments from some 83 nations annually – has emerged as a leader in the region for combining the visual identification guides for unprocessed fins with PCR technology to confirm species identification in the field. The result has been the seizure of more than 43 metric tons of illegal shark fins moving through Hong Kong since 2014.

There is a loophole, however. If there are individual fins in a shipment that are not positively confirmed to be from a listed species in a seized shipment, those products are released to the importing individual or company. And so, the species that are trickier to identify slip through the conservation cracks.

But herein lies the value of the second part of the study: a cheap (US$1, after the initial equipment investment) and fast (quicker than four hours) PCR test will complement visual identification guides, providing border officials with as many tools as possible to positively identify fins.

There is a strong chance of conservation success if trade is properly regulated. The enforcement of CITES regulations would discourage the retention of these species and promote live release over landing, as the local market value of their meat is low. This is what is needed to enable these species to recover and potentially open up the option for sustainably managed fisheries in the future.

References

Demian D. Chapman, Diego Cardeñosa, Kwok Ho Shea, Elizabeth A. Babcock, Rima W. Jabado, Huarong Zhang, Stephan W. Gale & Kevin A. Feldheim. Ongoing trade of fins from critically endangered rays (wedgefish and giant guitarfish) despite international regulations and a novel PCR test to detect rays among ‘shark’ fins. Conservation Genetics. 2025

DOI: 10.1007/s10592-025-01716

Read the paper here.