Satnav in the sea?

Sharks use magnetic maps to migrate

Can you imagine attempting to travel thousands of miles without a map, compass, or GPS to guide you? Many of us would struggle to navigate across a city this way. Yet, migratory marine species manage to navigate their way across seemingly endless oceans to the same locations year on year. Sharks are one of the most iconic migrants, travelling thousands of miles to feed or mate, often at incredible speeds.

So, how exactly do they do it?

Well, that’s a question we’ve been trying to answer for a while. In turtles, researchers have found evidence of magnetoreception – the ability to detect Earth’s magnetic field. It’s thought that females use this sense to guide themselves faithfully to the same nesting beach every year.

Could the same be true of sharks?

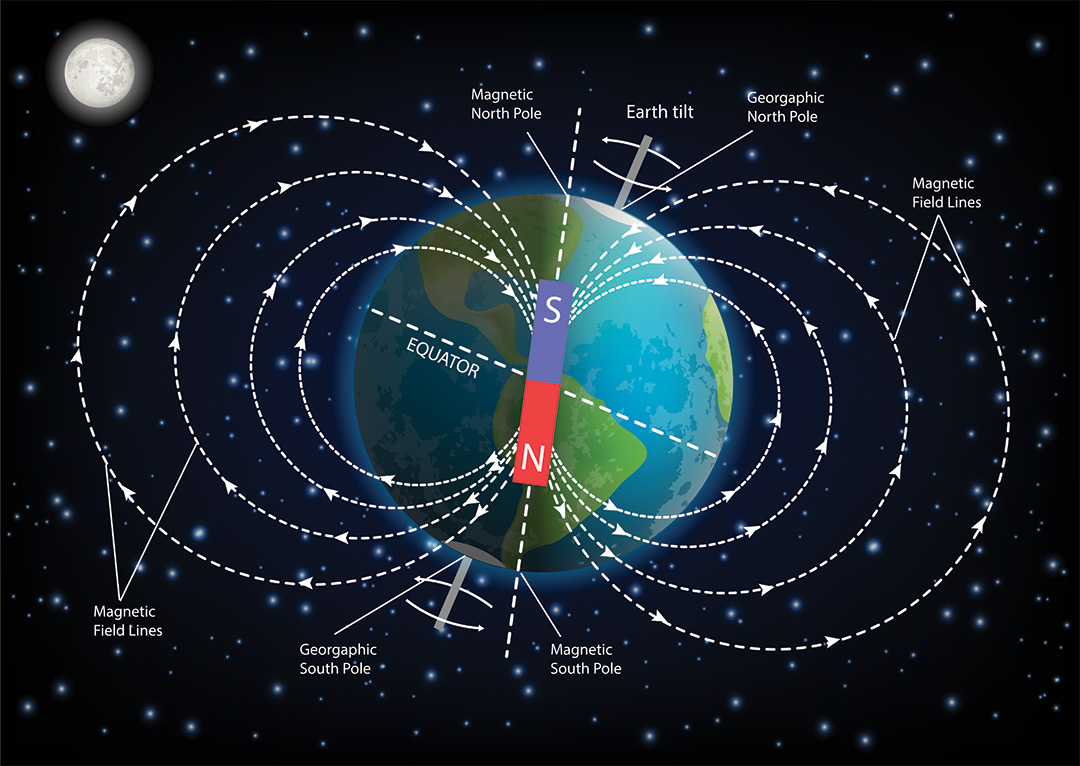

We know that sharks are also sensitive to Earth’s magnetic fields. We’ve even found that swimming direction in wild sharks seems to be associated with the magnetic signals around seamounts and feeding grounds. But do they use this sense to navigate, like a magnetic map?

Scientists have long speculated that this might be the case, but sharks are notoriously difficult to study. Their elusive nature means they can be hard to find, and tricky to research. Despite them being really important species ecologically (many are top predators, controlling the populations of other ocean life) we still know relatively little about them.

But now we’re beginning to unravel the mysteries of shark migration. In a new study in Current Biology, scientists have provided the first solid evidence of the use of these so-called ‘magnetic maps’ in sharks. They studied Bonnethead sharks, a species that are relatively easy to study due to their small(ish!) size, with a maximum length of around 120 cm. Bonnetheads return to specific locations, like their ‘home’ estuary or bay, every year.

The theory was simple – that sharks use the Earth’s magnetic field like some kind of satnav in the sea, giving them the same information as a map and compass, so they can successfully migrate to specific locations.

To test this, the researchers captured 20 juvenile Bonnetheads off the coast of Florida and transported them to their specialist marine lab at Florida State University.

They used ‘magnetic displacements’ to expose the sharks to magnetic conditions which represented locations hundreds of miles from where they were caught. They tested three different magnetic locations in the lab: the capture site (‘home’); south of the capture site (in the Gulf of Mexico); and north of the capture site (continental USA). Shark movements were recorded using a GoPro.

How did they respond to each magnetic location?

Their findings solve some of the puzzles of how migratory routes are maintained in the marine environment – where sharks are pretty much free to go where they want when they want. When sharks were exposed to the southern magnetic location, they moved northwards, towards ‘home’. Interestingly, when they were exposed to the northern magnetic location (Continental USA), not much happened. This could be because this is an unfamiliar place for the sharks.

All of this suggests that a shark’s magnetic map might be learned.

Fascinatingly, these magnetic differences could even be part of the reason for genetic differences between shark populations. The researchers found this to be particularly true when looking at the mitochondrial DNA – a part of the genome that is only passed on from the mother. This makes sense because females show an even stronger affinity to areas like their nursing grounds, where they return to breed than males.

So, sharks use magnetic maps by sensing Earth’s magnetic field to guide their migrations. And this amazing ability may even explain some of the genetic structure of their populations. Research like this, supported by Save Our Seas Foundation, is crucial in our efforts to conserve these understudied yet extremely vulnerable species.