Resounding support for sharks and rays at CITES CoP20

It was action over extinction as shark conservationists ended 2025 ringing in success at the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES) CoP20 as over 70 species of sharks and rays received new protection from international trade. All international commercial trade was banned for Critically Endangered whale sharks, oceanic whitetip sharks and manta and devil rays. With listings that tackle the fin and meat trade, deep-sea sharks and the highly threatened ‘rhino rays’, it is clear that, after 50 years of CITES, sharks and rays are finally firmly on its conservation agenda.

‘Interesting fact,’ begins Sarah Fowler, a Save Our Seas Foundation scientific adviser who recently participated in the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES) CoP20 in Samarkand, Uzbekistan. ‘The Appendix II listing proposal for smoothhound sharks (genus Mustelus) and the tope shark was the first listing proposal for a globally distributed, commercially important shark taxon to be adopted by consensus by a CITES CoP.’

When Sarah says ‘by consensus’, it’s important to understand how this is significant. More than 20 years ago, the whale shark and basking shark first made it onto CITES Appendix II – and it was a battle hard won. It was considered nearly impossible to get sharks onto the trade agenda. Getting the first commercially traded sharks listed on Appendix II was an even longer road. But this year, decades of scientific research came to fruition when decision-makers heard the proposals for the 70-odd species of imperilled sharks and rays to be listed on CITES appendices and unanimously agreed to add regulation and protection for most of them.

‘CoP20 also saw the first consensus adoptions of two Appendix I uplisting proposals – manta and devil rays, and the whale shark,’ says Sarah. ‘And there was a vote on the oceanic whitetip shark.’

Infographic by Kelsey Dickson | © Save Our Seas Foundation

‘We even saw record margins of victory in the species that did go to a vote,’ adds Dr Mark Bond, a researcher and assistant professor at Florida International University. ‘To have that scale of change roughly two decades after many of these species were first listed, and just over 10 years since the first commercially traded sharks were listed, really shows that sharks are becoming a group that are not just thought of as “bycatch”. And it’s also major recognition that, for many species, the key threat they face is overfishing to supply demand in international trade.’

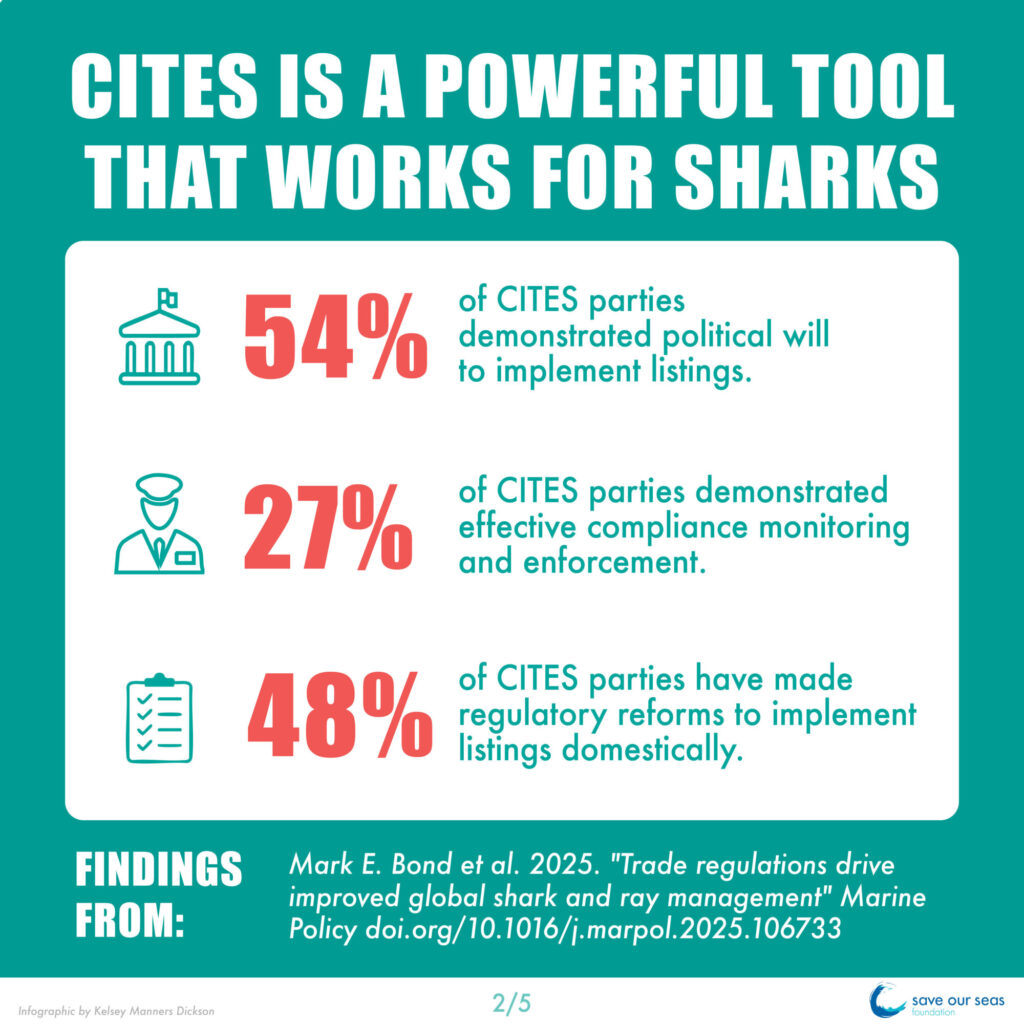

Mark’s most recent publication started tracking the impact and efficacy of CITES listings for sharks and rays. And while these most recent listings are in no way a conservation success since they represent population declines that signal major concern, Mark does agree with Sarah – and the many scientists and policy-makers who compiled the proposals for sharks and rays at CoP20 – that they indicate something of a sea change in how these overfished, highly threatened marine vertebrates are regarded in international conservation and policy.

Infographic by Kelsey Dickson | © Save Our Seas Foundation

‘I would say’, he continues, ‘that the listings – especially the Appendix I listings of highly traded and commercially valuable species, most of which were adopted by consensus – show a real shift, and a global shift at that, in the understanding and appreciation of the conservation concern for sharks and rays.’

What is CITES and how does it work?

The Convention on the International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES) is an agreement between governments to prevent the extinction of plants and animals by ensuring that the trade in their products is regulated and sustainable.

Animals and plants are listed on CITES according to three different appendices – Appendix I, II and III – that each indicate a different threat level. Each appendix applies a different level of trade control and therefore offers a different level of protection. Sarah explains, ‘When there is clearly illegal and/or unsustainable trade in severely threatened species, an Appendix I listing is considered to be the best option available.’ Appendix I offers the highest level of protection and is reserved for species threatened with extinction, as trade in these products is only permitted under special circumstances. Trade in these species caught or collected in their natural habitat is illegal and only allowed for non-commercial purposes, such as for scientific research.

I thought we saved sharks last CITES. So what was on the agenda at CITES CoP20?

The CITES CoP19 in 2022 achieved something incredibly ambitious: the entire family of 56 requiem shark species, one of the largest and most traded families of sharks in the world, as well as all six small hammerhead species and the remainder of the guitarfish family, were listed on Appendix II. It was a move that shifted the needle from regulating 25% to more than 90% of the shark-fin trade.

Many new findings had come to light since the first shark listings in 2003, and climate change had become the reality that is now shaping our oceans. It poses a serious threat to how Critically Endangered species like whale sharks and oceanic whitetip sharks could feasibly recover from overfishing and a level of trade that their biology simply could not sustain.

Simply put, not all fish in the sea can be fished in the same way: species like sardines have a live-fast, die-young strategy that is quite different from that of manta rays. And even populations of fast-growing, quick-to-multiply species collapse when they are incorrectly managed – and face compounding issues of climate change and pollution. Moving oceanic whitetip sharks, whale sharks and manta and devil rays from Appendix II to Appendix I recognises their very different strategy. Experts from the Manta Trust point out that the incredibly conservative and vulnerable biology of manta and devil rays means that we probably should never have let them be fished and traded to this extent in the first place.

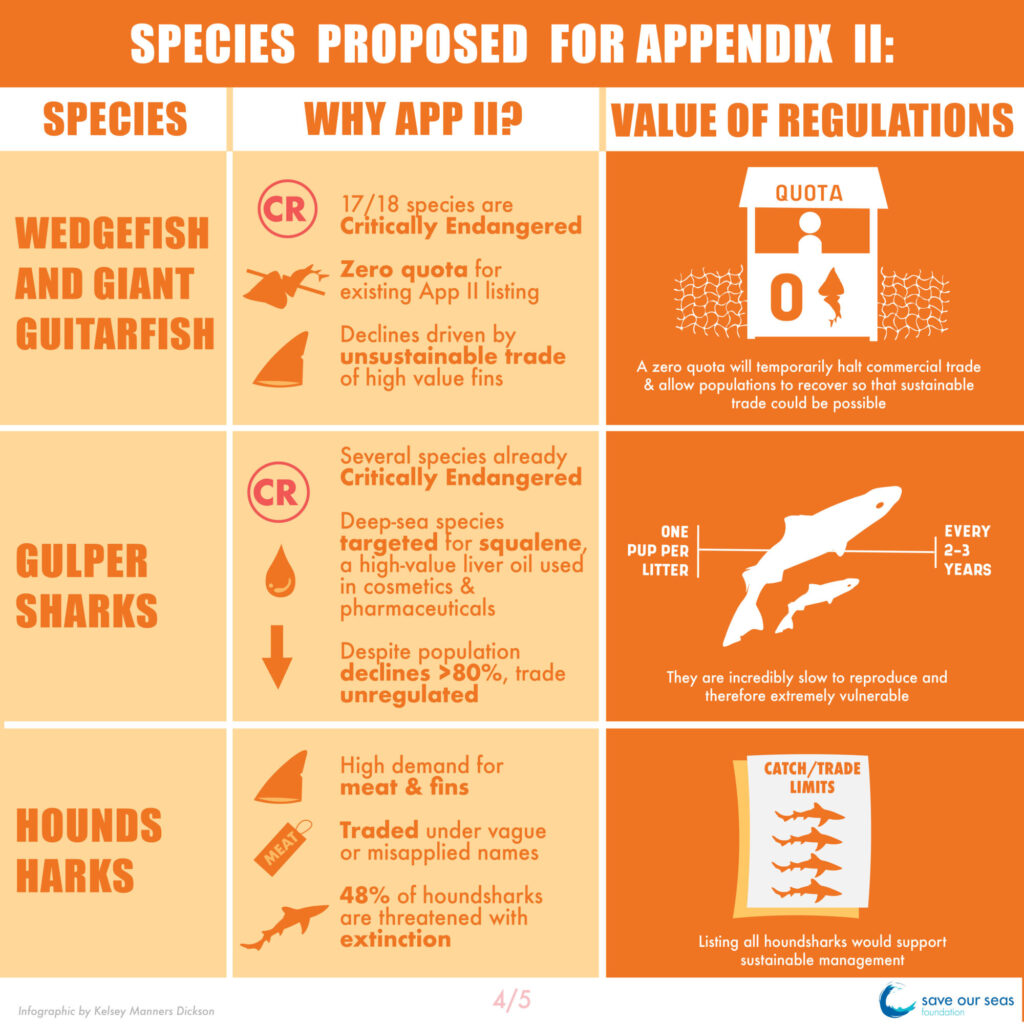

Up for consideration were also species we’d not known much about previously, like the deep-sea gulper sharks. And while shark fins are of higher value than shark meat and the global fin trade has received more attention, the global trade in the meat of sharks and rays is larger in volume and value than the global trade in fins. CoP20’s proposal that the houndshark family be regulated marked an important step for species that have been seriously impacted by both trades.

Critically Endangered sharks and rays get the same protection as elephants and rhinos

In a landmark policy moment, Critically Endangered whale sharks, oceanic whitetip sharks and manta and devil rays were granted CITES’s highest level of protection when the proposals to move them from Appendix II to Appendix I were approved. ‘Incidentally’, says Sarah, ‘the Appendix I listings agreed to here (two out of three by consensus) were for species listed a long time ago: about 20 years ago for whale sharks, 15 years ago for oceanic whitetips and almost 10 years ago for manta and devil rays.’

Mark explains further. ‘The Appendix I listings for whale sharks, oceanic whitetips and manta and devil rays harmonise regulations that exist across multiple multilateral environmental agreements, most notably the Convention for Migratory Species (CMS). There is always discussion on how best to harmonise these multiple agreements because some countries adhere to certain ones and not others, and vice versa. And so I think that by having an Appendix I listing, considering that CITES just focuses on international trade, makes life easier for enforcement officials because they don’t have to discern which regulations to enforce depending on threat and circumstances. There is just a blanket ban on fishing domestically and in areas beyond national jurisdiction (for CMS) and on international trade (for CITES).’

According to the Manta Trust, overfishing is driving manta and devil rays into decline. These rays are caught both incidentally and as the target of fisheries, and are retained to supply a lucrative demand for gill plates in Asian markets and an international meat trade, as well as domestic markets for meat consumption. The Manta Trust’s Betty Laglbauer published her findings (with a huge cohort of co-authors) last month and showed that fisheries kill around 265,000 rays each year, mostly in small-scale fisheries (small-vessel fisheries account for 87% of global mortalities). India, Indonesia, Sri Lanka, Peru and Myanmar are hotspots for highest risk and collectively account for 85% of all catches.

By making all international trade in manta and devil rays illegal, much of the reason for targeting them is gone. ‘But a large effort will be needed in years to come to track any remaining illegal trade, monitor a potentially adaptive and elusive black market and eliminate the demand for gill plates,’ cautions the Manta Trust. ‘Halting fisheries-related declines in manta and devil rays also includes many other things, like addressing gaps in protective legislation in key nations, enforcing already existing national and international protections, better population and landings monitoring, implementing safe handling and release guidelines, and encouraging alternative livelihoods for fishing communities. But the prohibition of trade can be a game-changer and a wake-up call for manta and devil ray protection worldwide.’

Jonathan R. Green A scientist swims alongside a huge female whale shark to get her photo ID at Darwin Arch.

A lifeline for deep-sea dwellers

Gulper sharks are deep-sea dwellers that grow very slowly, mature late (some species take longer than 20 years to grow to adulthood!) and give birth to one pup every two to three years. This makes these sharks extremely vulnerable to fishing pressure – and yet, because their large livers with their high squalene content (used in skincare and supplements) have the highest-value liver oil, gulper sharks are increasingly overfished throughout their range as both target and bycatch species.

Once they’re overfished, gulper sharks are unlikely to recover easily, if at all, as researcher Brit Finucci and her colleagues have convincingly shown. In fact, gulper sharks are gaining notoriety as one of the ocean’s most endangered groups: 11 of the 15 species are now considered threatened. In some places, their numbers have dropped by up to 80%.

Aside from their popularity in trade, these sharks are very difficult to distinguish from one another once they have been caught and are being circulated in international markets. So it makes cautionary sense to have gulper sharks listed on Appendix II, which will require trading nations to supply a non-detriment finding (NDF) and impose the first major regulation that these species receive in international trade.

Closing the gap in the trade in shark fins and meat

‘The shark listings adopted by CITES CoP19 in Panama three years ago brought more than 90% (by volume) of the international shark-fin trade into regulation. Most of this volume is blue shark fins,’ explains Sarah. “But there was still a big gap in regulation of the fin trade in smaller shark species, such as the houndshark family (including tope and smoothhounds), which made up about one third of the small fins sampled recently in Hong Kong markets. More than 20% of all small shark fins were from smoothhounds. Tope was the 14th most highly traded species in the global shark-fin trade overall, despite the huge reductions in its populations and legal protection for some stocks.’

The family Triakidae is made up of 40-odd small and medium-sized sharks that are widely eaten around the world, especially in southern Europe. In many places, their meat isn’t labelled, so many consumers have no idea that their fish and chips is one of these little sharks.

‘Since more than 90% of the global fin trade was already regulated following CoP19, the focus has now shifted to the trade in shark meat (and, to a lesser extent, shark liver oil),’ Sarah continues. ‘Tope, as one of the larger of the small coastal sharks, has been targeted for its meat since well before records began. As an interesting aside, a Save Our Seas Foundation (SOSF) project investigated one of these fisheries (which also took other, smaller houndsharks) and incidentally identified some of the first records of international trade in tope fins.’

We also now know, thanks to Dr Aaron MacNeil and colleagues, that volumes of small coastal sharks in the international meat trade are far larger than previously realised and that after excluding blue shark, surprisingly, the pelagic sharks (already listed in CITES) are less important than we thought. Excluding blue shark, the common smoothhound is the fifth most abundant in the meat trade, the tope shark is the ninth and the Patagonian narrownose smoothhound (astonishingly, considering it is so badly depleted) is 17th. Two other smoothhound species, listed as look-alikes, are also in the top 20.

Three endangered species – the tope shark (Galeorhinus galeus), common smoothhound (Mustelus mustelus) and Patagonian narrownose smoothhound (M. schmitti) – and 26 look-alike species in the family are now listed on CITES Appendix II. ‘The CITES II listings, for stocks where the development of NDFs encourages better data recording, will provide better-quality information on quantities of animals in trade to supplement fishery data and can also be used in stock assessments,’ says Sarah.

‘As long as Appendix II is implemented and enforced well, then it should do virtually the same job for species affected by unsustainable fisheries,’ she concludes. ‘This is because of the CITES system behind the issuing of export permits. The products require a form of certification that testifies they have been acquired legally and are non-detriment (that is, trade in them must be sustainable), and it must be possible to trace them between exporting, importing and re-exporting countries. Appendix II is also the only option for regulating trade in look-alike species. Only when there is clearly illegal and/or unsustainable trade in severely threatened species is Appendix I considered to be the best option. The other option available is a zero quota for Appendix II species, which also prohibits international trade but may be regarded as more temporary or reversible than Appendix I.’

Deceased juvenile barbeled houndshark found on the shores of Nouadhibou. Photo © Carolina de la Hoz Schilling

Reprieve for ‘rhino rays’

Finally, zero-quota listings were agreed, by very large majorities, for wedgefish and giant guitarfish species. These highly threatened members of the ‘rhino rays’ group are the species with the most coveted fins in international trade. Even though wedgefish and giant guitarfish were already listed on Appendix II, their severe declines and their high value in trade warranted more immediate action: a study in 2019 had suggested that other slow-growing species (shovelnose rays) could potentially recover if fishing mortality was kept low. A zero-export quota for wedgefish and giant guitarfish pauses trade until their populations can support sustainable trade limits and would prevent an Appendix I listing in the future. This measure encourages the development of domestic management measures and data collection.

A bottlenose wedgefish glides over the sandy ocean floor, Republic of Maldives. Photo © Sirachai "Shin" Arunrugstichai | Crossroads Project | Singha Estate