The X, Y and white sharks; capturing chromosome information

Szu is diving deep into the DNA of white sharks, hoping to capture the first clear images of their chromosomes and sex chromosomes. Part of his aim is to develop the research methodology in a way that is minimally invasive for these animals, and that the process is repeatable and consistent. The results will also help inform the growing field of genomic bio-informatics, supporting the ability to draw conservation conclusions from genomic research with higher confidence.

I was born and raised in Taipei, the capital city of the island country of Taiwan. Surrounded by the Pacific Ocean on all sides, I was constantly reminded of how vast and beautiful an ocean is. As my fascination for biodiversity grew, I leaned into marine biology studies as an undergraduate student, which led me to work with marine fish diversity surveys and undertake taxonomic studies of deep-sea fish, and to my first close interactions with the diverse sharks and rays in these habitats. During this time, I witnessed the beauty of marine organisms as I constantly encountered...

Karyotyping the Great White Shark

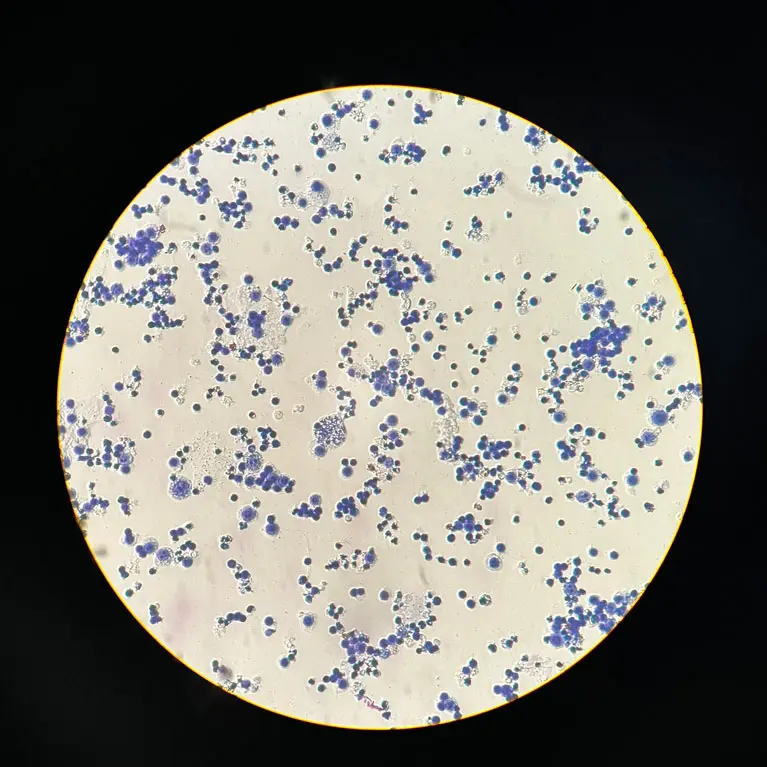

Our objective is to observe and record the chromosome morphology of the white shark by maintaining the species’ blood cells in the laboratory and conducting experiments on the chromosomes.

We want to establish a reliable characterisation of the chromosomes and the sex-specific features of karyotypes in the white shark. This will inform us about sex-determining mechanisms and potential chromosome abnormalities. We will also use the information derived from karyotyping to help our genome assembly work, which will tell us about the population histories, the genes and the potential challenges facing this species.

Sharks are generally considered to have XX/XY sex determination. However, direct evidence from observing the chromosomes has been limited. Shark and ray species whose chromosome numbers and sex chromosomes are known are mostly species that can be kept in an aquarium or are easy to capture. It is far more challenging to obtain this information for large, live-bearing species such as the white shark due to the difficulty of obtaining fresh tissue samples.

While genomic evidence for XX/XY sex determination systems has been emerging in recent years with genome assembly technologies, assembling sex chromosomes can be difficult because of their complex structures, and cytogenetic evidence is required as independent support. It has been reported that the white shark has about 82 chromosomes and a heteromorphic chromosome pair in males, indicating the X and Y chromosomes but without the support of images. Even though we have genome assemblies for the white shark with the X and Y chromosomes, some fragments suggest that some sequences are missing. We therefore want to use the newer methods from recent studies to collect the chromosome images of the white shark and potentially other endangered shark species. These will help us to understand their reproductive system, monitor any chromosomal abnormalities and explore the karyotype evolution of the sharks. We can also use these results to help verify or detect any potential missing pieces when assembling their genomes.

- To acquire and record clear chromosome images of male and female white sharks to observe their chromosomes and sex chromosomes.

- To establish a practice where we can do this consistently and minimise the harm to the animals.

- To use these results to help inform our work on genomic bio-informatics, which can allow us to make conservation inferences from the genomes with even higher confidence.