Disentangling the drivers of Antarctic Peninsula penguin colony declines

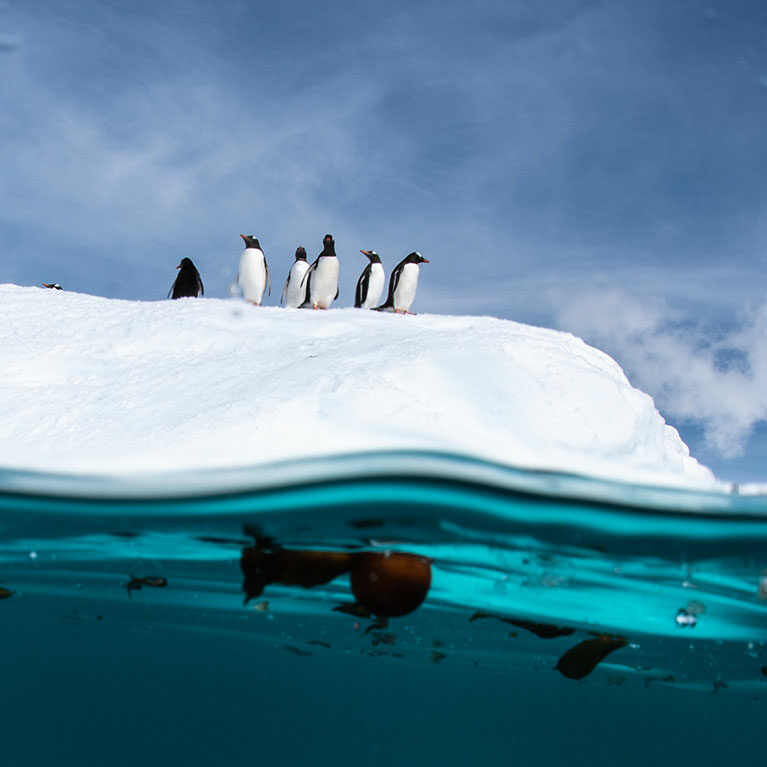

Tom has a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to tease apart the impacts of human visitation, climate change and fishing on Adélie, Gentoo and Chinstrap penguins. Using drone footage, camera data and faecal samples collected in 2020/21 and into 2022, he’s monitoring Antarctica in years with minimal human footprint due to the Covid-19 pandemic. Tom wants to know whether rising sea temperatures, increasing krill fishing or a growing tourism presence is driving declines of Antarctic Peninsula penguins. By comparing 10 years’ of monitoring data to these data, he hopes to use his findings to inform policy decisions to conserve the Antarctic Peninsula’s penguin colonies.

I grew up in the United Kingdom, where I developed a passion for wildlife and extreme environments. I escape to cold and wild places as often as my research allows me and they are always a great reminder of what I am trying to conserve. I have dedicated my career to protecting the unique polar environments in a rapidly changing world. While my work requires analysis and data to change policy, I love that I can frequently get into the polar regions for field work and, particularly, to South Georgia with my favourite penguin species, the macaroni penguin.

Disentangling the drivers of Antarctic Peninsula penguin colony declines

With this project I aim to collect monitoring data in Antarctica and the South Shetland Islands in years when there has been virtually no tourism and very little scientific presence due to the Covid-19 pandemic. The decline of these two factors will help us to determine the effect of human visitation, climate change and fishing on penguin populations.

Penguin numbers have declined on the Antarctic Peninsula, but the drivers of this decline are unclear. By contrast, sea temperatures are rising and krill fishing and tourism are growing rapidly. Because these stressors overlap on the Antarctic Peninsula, it has been difficult to disentangle them to understand the causes of penguin decline. To separate the local threats (like fishing) from wider impacts like climate change, we collect data on a much larger geographical and temporal scale.

Seabird populations are threatened globally by pollution, climate change, fishing and other human disturbances. With my team, I have been monitoring populations across the Scotia Arc since 2009 and have built up a 10-year dataset using time-lapse cameras, drones and counts on the ground, as well as a time series of samples that we use to monitor penguin disease, diet and stress. The Covid-19 pandemic has created a unique natural experiment in which the effective removal of tourism and the temporary closure of many national research programmes means that we are able to unravel some of the threats penguins face in the Southern Ocean.

Using faecal samples and drone/camera data collected from the 2020–2021 and 2021–2022 field seasons, we intend to:

- Analyse samples of penguin poo for stress hormones and compare these with samples taken when more humans are present;

- Obtain a baseline pattern of penguin population numbers and behaviour and look for changes in response to climate change and fishing;

- Explore the overlap between fishing effort and penguin colony foraging areas.

We will use the monitoring data collected over the past 10 years to compare the years with virtually no human presence to historical data. This will help us to disentangle the effect of human visitation, climate change and fishing on wildlife and better inform policy decisions to conserve the Antarctic Peninsula’s penguin colonies.