Attitudes and costs from a new conservation challenge

The Maldives served as a shark sanctuary for 15 years and its hard- won conservation successes have meant that it remains one of the most diverse regions for sharks and rays. But with success comes a new cost: shark population recoveries have brought conflict with fishers, who lose some of their catch to sharks in what is termed depredation. Mina wants to understand the economic cost of and attitudes to depredation, and how depredation impacts local opinion about sharks and the shark sanctuary. She will co-develop mitigation strategies with fishers, taking into account our warming world, and assess how engaging and empowering fishers affects their perceptions.

Growing up in the landlocked state of Colorado in the USA, I never thought I’d feel especially connected to the ocean. Instead, I grew up roaming forests and climbing mountains. When I was 17, my high school science teacher pushed me to embrace an opportunity to join a marine conservation programme as a volunteer and learn to scuba dive. Descending into the depths of a foreign world was a daunting concept for my mountain-raised self, but never one to back down from a challenge, I went for it. From the first moment my head submerged beneath the surface,...

Are hot sharks hungry sharks? Understanding drivers and solutions for depredation amidst a changing climate

This project investigates social, ecological and physiological factors influencing shark depredation in the Maldives and aims to co-develop climate change resilient mitigation strategies with fishers.

The Maldives harbours incredible shark and ray diversity and has a complex history of how sharks and rays have been used. The nation’s waters were designated a national shark sanctuary in 2010, but November 2025 sees the complete ban on shark fishing being lifted. Increasing concern about shark depredation has contributed to loss of fishers’ support for shark conservation initiatives. Understanding the socio-economic factors involved in depredation is crucial for proposing effective mitigation strategies to create long-lasting and sustainable positive outcomes for shark conservation, while safeguarding the livelihoods of small-scale fishers.

The Maldives supports a high diversity of sharks and rays, and its waters served as a national shark sanctuary for 15 years. Today, a new challenge has emerged that threatens hard-won conservation goals in the region: shark depredation. Simply put, shark depredation is when a shark consumes the catch off a fisher’s line before it can be retrieved, resulting in loss of income. Surveys of affected fishers have discovered that many believe that increasing incidents of depredation are evidence of the recovery of local shark populations, directly related to the success of the shark sanctuary. Loss of income for these small-scale fishers threatens their ability to provide for their families, and so unfortunately depredation has diminished fishers’ support for shark conservation.

Two species commonly implicated in depredation events in the Maldives are the blacktip reef shark Carcharhinus melanopterus and the grey reef shark C. amblyrhynchos, which are listed as Vulnerable and Endangered respectively on the IUCN Red List. In addition, ecological data in the region are insufficient to confirm suspicions of these species’ increasing populations. Shark depredation in the Maldives is therefore a key human–wildlife conflict that must be addressed to balance the security of small-scale fishers’ livelihoods with the long-term sustainability of shark and ray conservation objectives.

Meanwhile, rising temperatures in the ocean threaten to alter the metabolic requirements of many marine animals. This will invariably change the interactions between sharks and their prey, fishers and their catch and, subsequently, fishers and sharks. For this reason, shark depredation requires mitigation strategies that are flexible and inclusive of the effects of climate change. In order to achieve this, we need to understand the social, ecological and physiological factors involved in shark depredation.

- To understand the extent and impact of depredation and the social dimensions of depredation conflict.

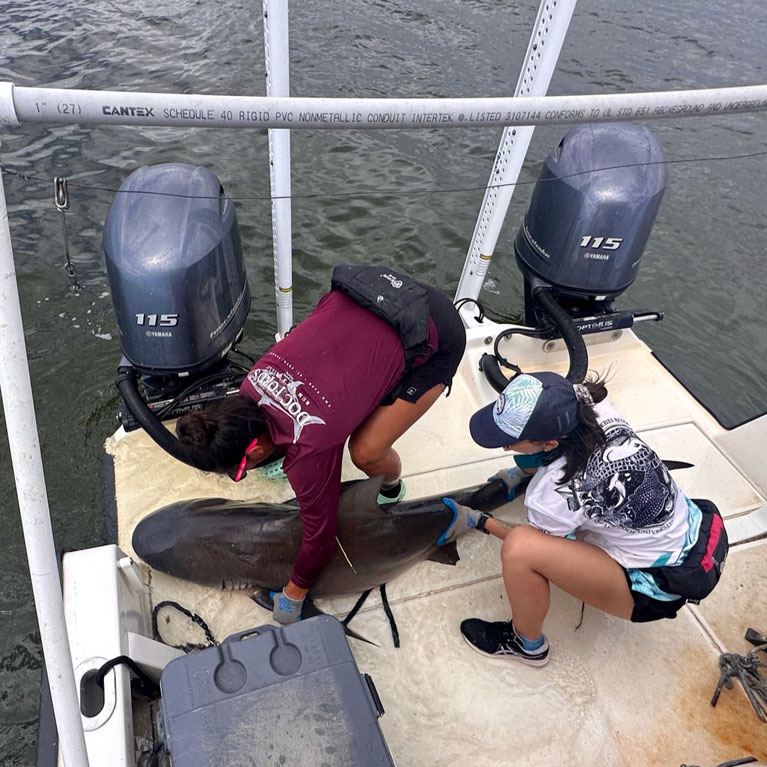

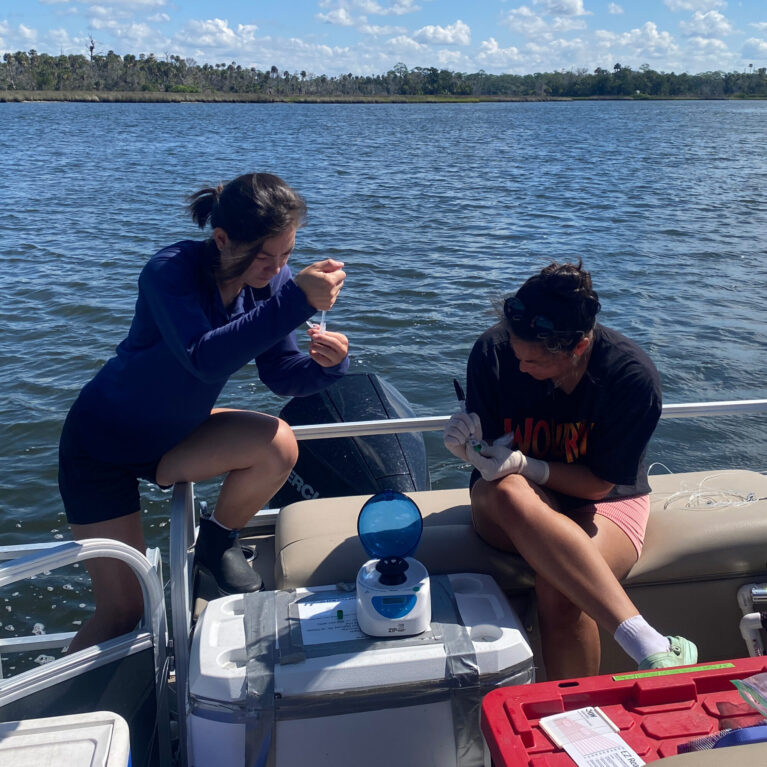

- To quantify depredation instances and assess environmental and ecological factors such as shark ecology, habitat use and behaviour, which may contribute to fisher-shark interactions.

- To understand how shark metabolic requirements change with water temperature and predict metabolic requirements of sharks under predicted future ocean temperatures to inform adaptable and resilient depredation mitigation strategies.

- To co-develop understanding of and mitigation strategies for shark depredation with fishers.