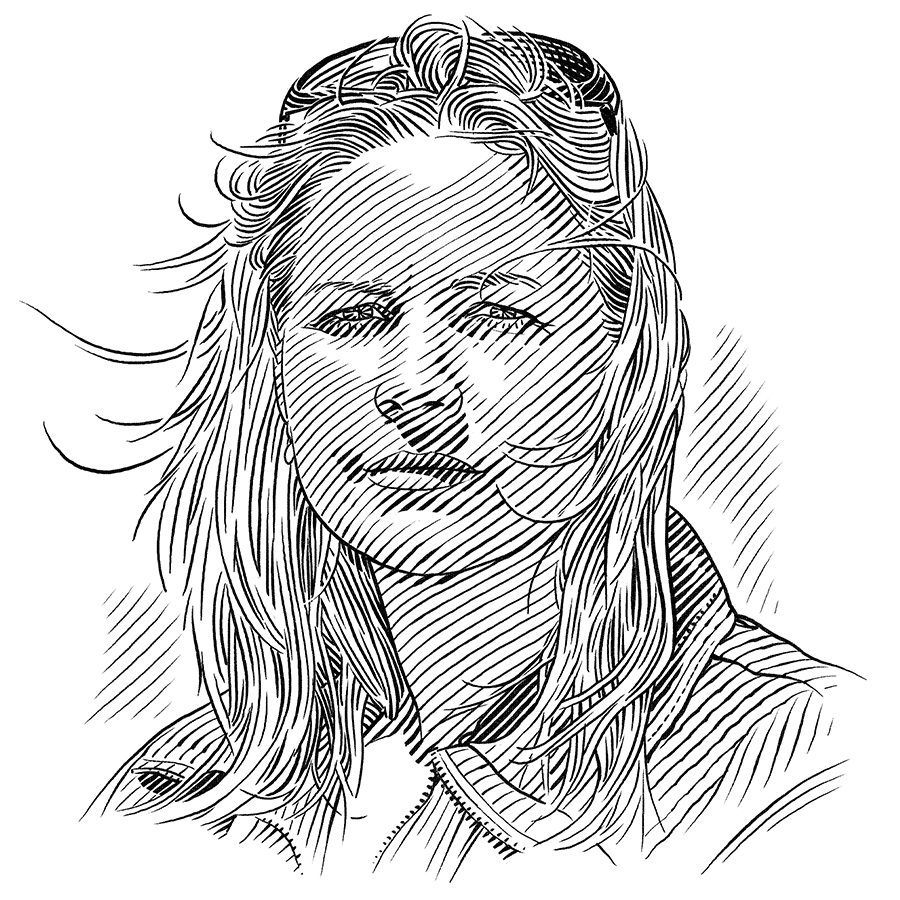

Alison Kock

Who I am

‘My goal is to be a marine biologist.’ This is the hand-made banner that I displayed above my desk all through high school. I have always wanted to be a marine biologist and was fortunate to have parents who fostered my love for the ocean. When I was very young I used to accompany my dad on boat trips to harvest crayfish. We would spend hours at sea, deploying nets and waiting for the crayfish to climb inside. When we retrieved the nets, it wasn’t only crayfish that we found, but small shysharks too. The little sharks would curl up into a ball with their tail covering their eyes and my dad instructed me to kiss them on the head and gently release them back into the water. When I did so, the shysharks would uncurl and swim back down to the bottom.

After high school I enrolled at the University of Cape Town to pursue my career in marine biology and at every opportunity I spent my free time scuba-diving and exploring the incredible underwater world around Cape Town. After my undergraduate degree I had the opportunity to go out on a white shark viewing trip to Seal Island. That was the first time I saw a great white shark launch itself two metres into the air chasing a Cape fur seal. I was hooked. I decided then and there that I was going to be the one to discover the answers to all the questions nobody could answer.

Following a four-year period when I worked as a field guide on the ocean with the sharks and in the terrestrial environment with other wildlife, I went back to university and initiated a research project on the behavioural ecology of white sharks in False Bay, which was one of the six inaugural projects funded by the Save Our Seas Foundation. Seventeen years since my first great white shark sighting, I am still studying these sharks, now in the role of research manager for Cape Town’s pioneering Shark Spotters programme. I no longer kiss the sharks on the head, but I did achieve my goal and have my dream job.

Where I work

Cape Town, South Africa, is a major city with an ocean wilderness as a backyard. It encompasses False Bay, a special place where you can visit African penguin colonies, view massive southern right whales breaching up to 15 times in a row from shore, encounter thousands of common dolphins on a boat trip, watch fishermen hauling in nets filled with yellowtail and, if you’re lucky, sit at a mountain lookout and watch great white sharks swim lazily by.

Just six kilometres from the coast is a small granite island that is home to 70,000 Cape fur seals at the peak of the season. It is here that you can witness the incredible raw power of the sharks as they pursue their seal prey in a game of survival. Nowhere else on earth can these encounters be observed with such consistency and it is a spectacle that deserves to be preserved.

One of the best things about working in Cape Town is that it is a hop, skip and a 20-minute boat ride to get to my field sites. This means that I can regularly and consistently conduct field work throughout the year. So far, my team and I have established that False Bay is a critical area for the conservation of white sharks because a significant proportion of South Africa’s white shark population uses the area throughout the year. But the sharks’ high fidelity to this coastal area has implications for them, as the environment is heavily impacted by fishing, pollution and disturbance resulting from coastal development. It also has implications for the large proportion of Cape Town’s four million residents who swim, surf, kayak, windsurf, kite-board, fish and dive along these shores. Shark incidents have increased over the years and conserving a threatened apex predator in conflict with people is a major conservation challenge. To maintain the balance between white shark conservation and public safety, I believe it is imperative that we have a strong scientific foundation on white shark ecology and behaviour, coupled with non-lethal mitigation methods to reduce shark incidents and supported by a comprehensive education and awareness strategy.

What I do

My role is to conduct applied research on the ecology and behaviour of Cape Town’s white shark population. So far my team and I have answered questions relating to the ‘when’ and ‘where’ of white shark occurrence. We have discovered that they are present all year round in False Bay, but use the bay very differently depending on the season. In autumn and winter, male and female sharks spend most of their time around Seal Island, preying on naive seal pups. However, come spring and summer, the sharks spend little time around the island and instead many of the female sharks move inshore, closer to the coast.

Although we have a good understanding of why white sharks visit the island, our understanding of why they spend so much time inshore is still limited. We do know that within the inshore area there are specific hotspots, like the northern shores of False Bay, which are used significantly more than other inshore areas. But we don’t know what makes the inshore area so attractive. We have also determined that most of the sharks are juveniles and sub-adults.

My research now focuses on the ‘why’. To achieve this goal I will use a combination of direct observation, photo-identification, acoustic monitoring and animal-borne cameras. With a hypothesis-driven approach, I will investigate the drivers of white shark presence in False Bay, both environmental (such as water temperature) and biological (such as prey availability). This will enable us to model which factors relate to high shark activity and can be incorporated into shark safety strategies.

Furthermore, I will examine the interactions between white sharks and their prey to define the species’ ecological role in a temperate ecosystem. Predators can shape the ecosystems in which they live in a direct way by reducing prey numbers, which in turn can affect populations lower down the food chain. They can also influence the structure and function of the ecosystem by causing prey populations to modify their behaviour in response to predation risk. I hope that with enough information we can predict what would happen to the ecosystem if their populations changed significantly.

The overarching goal is to contribute to the conservation of the South African white shark population, its critical habitats and its prey resources. Even though white sharks have an extensive range, their high site fidelity to False Bay gives us an opportunity to contribute to the long-term conservation of this critical habitat and continue to foster co-existence between people and sharks.