Overfishing: driving extinction

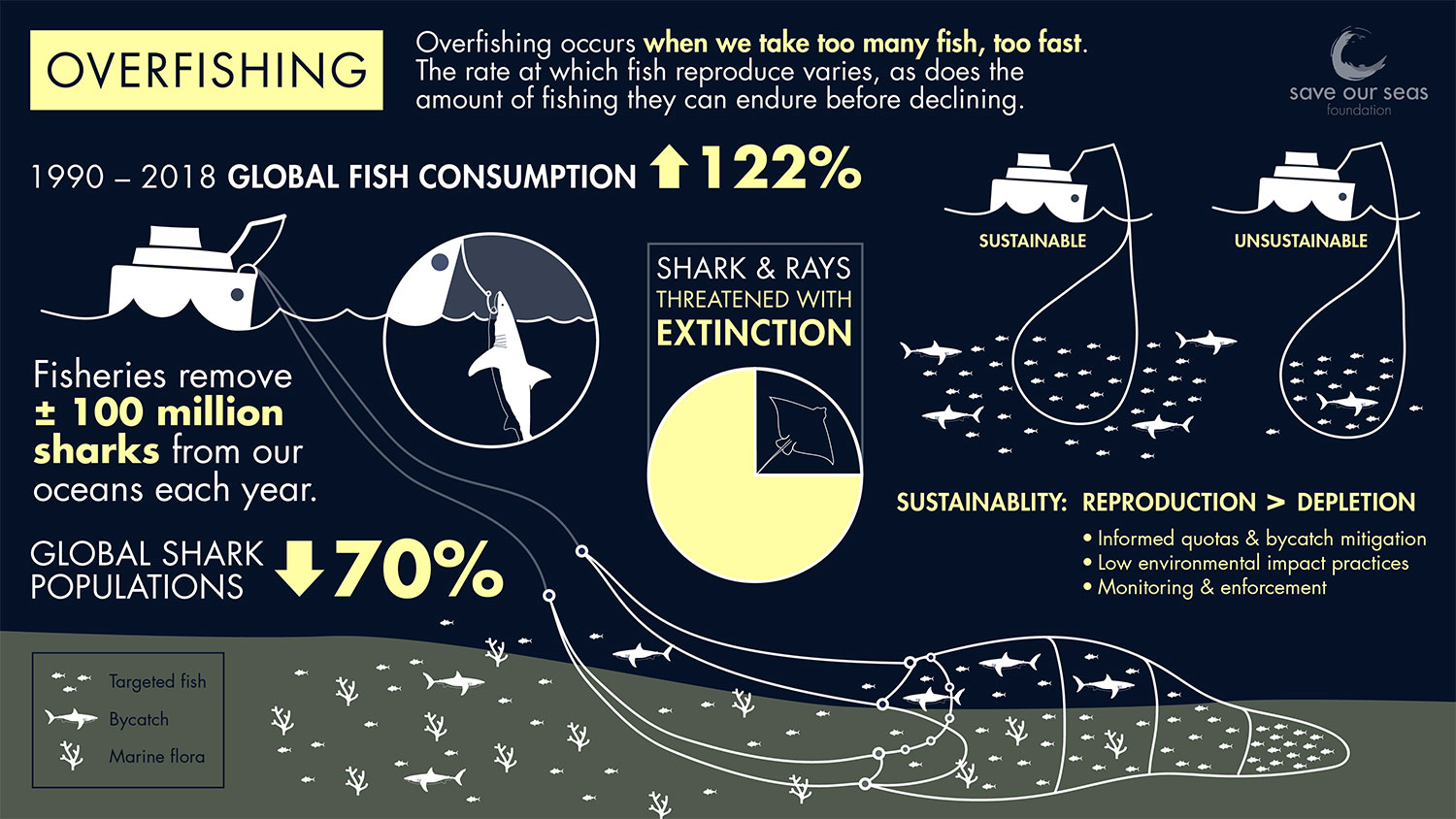

The latest IUCN Red List assessments for sharks and rays are in, and it’s official: overfishing is driving extinction.

For the first time since the initial IUCN Red List assessment, scientists, including the Save Our Seas Foundation’s Project Leader David Ebert, have reassessed the extinction risk to all 1,199 chondrichthyan* species. And the news is bad. Despite having survived at least five mass extinctions during their 420-million-year history, more than one-third (37.5%) are now estimated to be threatened with extinction. That’s up from around a quarter (24%) in 2014.

From the majestic reef manta ray to the giant great hammerhead shark, and even the bioluminescent velvet belly lanternshark, they all have one thing in common: they’re caught (often unintentionally) in fisheries, and it’s threatening their survival.

*Sharks, rays, and chimaeras (ghost sharks)

Whale sharks feeding around the fishing nets hanging from floating fishing platforms in Cenderawasih Bay, West Papua, Indonesia. Photo © Wildestanimal | Shutterstock

And it’s not just the ‘mega-stars’ such as the great white shark...

But the lack of media attention doesn’t mean these ‘lost sharks’ are free from the dangers of overfishing. Many are disappearing, some may have already gone extinct, and it’s hardly been noticed! A staggering 99.6% of all chondrichthyan species are threatened by overfishing.

The verdict is unanimous: fisheries, particularly industrial fisheries, have been found guilty of driving extinction.

Photo © Aymeric Bein | Shutterstock

But how exactly do fisheries unintentionally threaten sharks and rays?

It’s not that fisheries are purposefully targeting sharks and rays. Yes, sometimes they do catch them on purpose, often on account of the value of their fins or gill rakers. But more often than not sharks and rays are caught as incidental catch (or bycatch) by fishing vessels that are going after other species such as tuna. Sometimes they’re retained (kept onboard) and used (for their meat or for other products, like liver oil) and sometimes they’re discarded (thrown back into the ocean), dead or alive.

Sharks and rays tend to have long pregnancies and produce only a few young. On top of this, they may not reproduce every year. Overfishing is like felling a forest more quickly than it can regrow – and this is why we’re seeing such dramatic declines in populations that are heavily fished.

Recovery is no easy feat, but solutions do exist

So, how do we tackle overfishing? It’s not as simple as telling people not to fish sharks. ‘In many areas, and developing countries in particular, where sharks and rays are heavily fished, it’s for food security – people need to eat,’ explains David. The trade in shark meat, in fact, now tops that in shark fins. We need to work with the fishing communities in these areas to find new approaches that provide alternative livelihoods.

But what about industrial fisheries and incidental catch? The solution lies in science-based management, like the strict protection of species and the declaration of large-scale marine protected areas, and enforcing them efficiently. When this is done right, we know it can work. In fact, three species of skate have seen positive IUCN status changes since 2014 – and this is probably due to effective fisheries management!

The public’s perception of sharks often conjures up images of a large, fearsome, toothy predator, its large dorsal fin slicing through the water’s surface

‘However, the reality is that sharks and their relatives come in a variety of sizes, shapes and colours, and they can tell us about the health of the marine environment,’ says David.

Sharks are vital for the health of certain ocean habitats; among other things, they help to maintain balance in delicate coral reef ecosystems. As our knowledge of the depths increases, so does our ability to protect the vulnerable species that live in them. And by doing so, we’re helping to protect the ocean as a whole. The onus is on us, and one thing is for sure – we need immediate action today to prevent further extinctions tomorrow.

You can find out more about David’s work here, or find out more about how overfishing threatens sharks and rays on our World of Sharks website.

Artwork by Nicola Poulos | © Save Our Seas Foundation