Of penguins and a pandemic

They say that hindsight gives us 20/20 vision, but anticipating change might allow us to plan for a better future. And it may well be that the only certainty in our world is change, but predicting precisely what that change will be is not always an exact science. Two things then become important: planning to have a view of our world that allows us to measure rapidly the impact of changes when they happen and using our understanding to adapt and manage how we respond.

Dr Tom Hart leads the Polar Ecology and Conservation Research Group at the Department of Zoology at Oxford University. He is also a Save Our Seas Foundation-funded scientist working on a project that presents a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to investigate the potential drivers of decline in the populations of penguins on the Antarctic Peninsula. Tom’s work shows us the value of long-term monitoring and the importance of collecting baseline data at scale. While no one could have predicted the Covid-19 pandemic and its consequences for our planet, Tom’s research can now capitalise on a 10-year monitoring dataset that he can compare with these pandemic years of minimal human presence on the peninsula. The foresight to anticipate change – whatever shape that may take – is what makes this project uniquely placed to disentangle the complex impacts of human visitation, climate change and fishing on adélie, gentoo and chinstrap penguins.

When the world ground to a halt in 2020, Tom Hart’s mind leapt from where he grew up and now works in the United Kingdom to a wilderness seemingly far removed from the panic and confusion that gripped our planet. Many of us grasped at a chance to escape our newfound circumstances and it was not uncommon to hear how our enforced captivity had renewed our appreciation for access to the wild places we may once have taken for granted. The difference is that Tom’s thoughts were not on escape; they were sparks flitting around an idea he had been formulating for more than 10 years – and one that had him realising an unlikely but emerging opportunity. The prospect for any scientist of being stuck roughly 16,000 kilometres from the site of their life’s work to date is not typically a good one and around the world many datasets were interrupted or lost to scuppered field sampling seasons as pandemic-related policies kept us home. For Tom and his research team, the pandemic presented the chance to conduct a strangely serendipitous experiment. As it turns out, it may well be that the loss of access to those very wild spaces that we all lamented was precisely the ‘removal experiment’ that 10 years of Antarctic Peninsula penguin research needed.

Photo © Thomas Peschak.

A long journey south

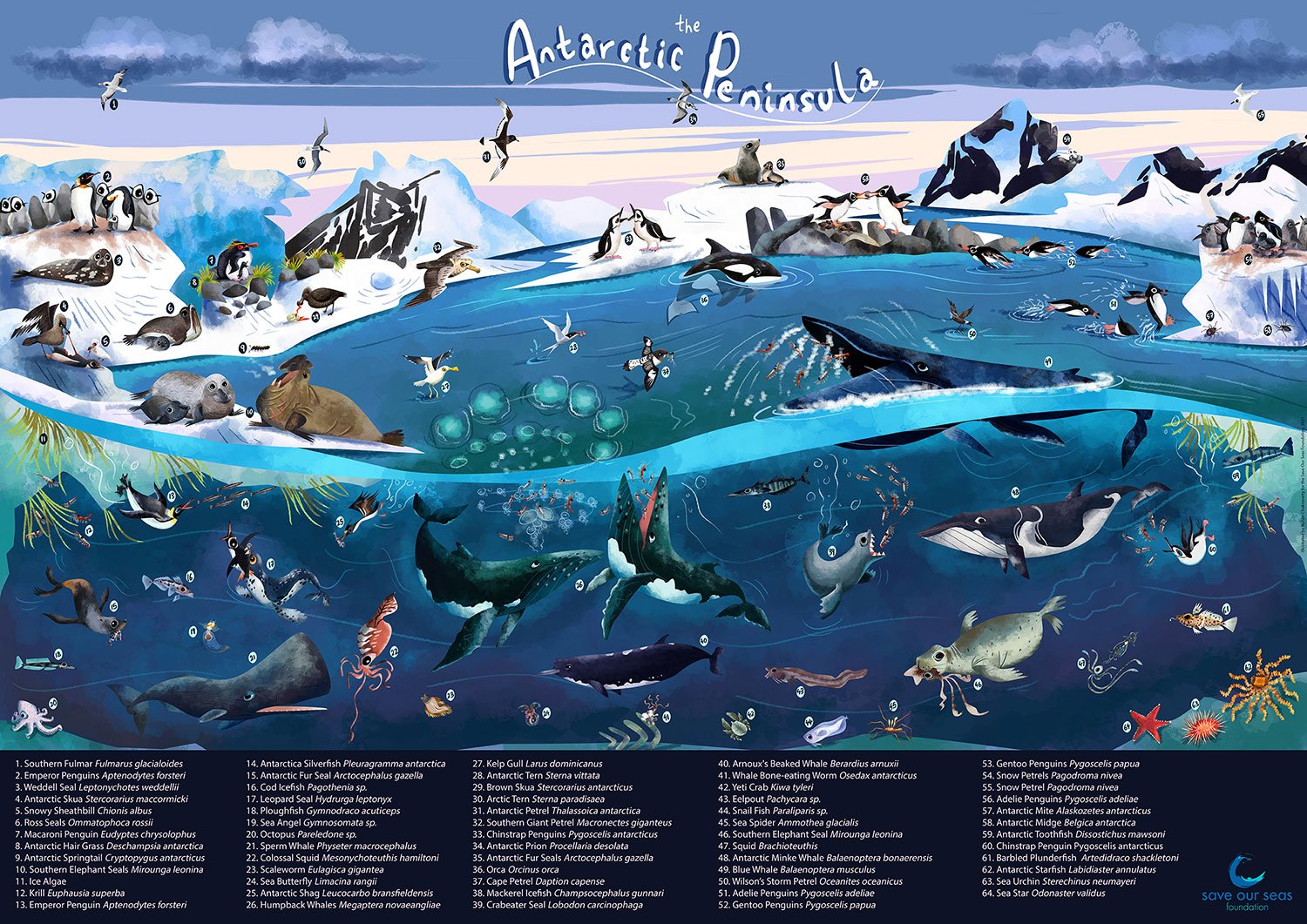

An ocean where the Antarctic Circumpolar Current (ACC) forms a swirling boundary between the slightly colder and less salty waters around the Antarctic continent and the waters to the north of 60° latitude. The Southern Ocean is ecologically rich and hugely consequential for the regulation of our planet’s climate. Bubbling with unique species found there and nowhere else, the productivity of the Southern Ocean also draws the ocean’s nomads to form part of its living tangle of ecosystem threads. The result is an ocean heaving with life; the frigid waters are a source of food for humpback giants, seals, seabirds and, of course, various penguin species.‘I fell in love with South Georgia on first seeing the island,’ says Tom.

Photo © Thomas Peschak.

Data and dedication: the basis for Penguin Watch

While South Georgia might have sealed the Southern Ocean deal for Tom, it was the appeal of penguins as a research focus for the reams of data they present that has seen him cement his work on the coastline of the Scotia Arc. Penguins have been anthropomorphised and idolised by those of us cooing over the likes of the hapless Adélie penguin, whose encounters with the criminal elements of its colony are recounted by David Attenborough’s narration as its nest pebbles are stolen by compatriots in the BBC’s Frozen Planet. But Tom’s commitment to the Adélie, chinstrap and gentoo penguins found on the Antarctic Peninsula and the South Shetland, South Orkney, South Georgia and South Sandwich islands comes from a different passion: that of process. Penguins make for excellent environmental health indicators by which to measure changes in the landscapes to which Tom feels most drawn. ‘It has to be a passion project at some point, otherwise, you simply wouldn’t do it,’ he says. ‘It’s hard and requires the tenacity that passion can give you. It’s just a question of whether that passion is for penguins or a landscape or a process.’

The result of this kind of scientific curiosity and conservation commitment was the projects Tom now runs through the Department of Zoology at Oxford University, including citizen science project Penguin Watch and its sister programmes, Seabird Watch, Seal Watch and the Arctic Bears Project. The aim is to understand how marine predator populations are changing, and in doing so to provide sound scientific data that can underpin strong policies and suitable protection around the Antarctic Peninsula. To achieve this, Tom and his team maintain a network of more than 140 time-lapse cameras across the Scotia Arc that capture images every hour (allowing them to gather hourly data for two continuous years) or, in the case of a penguin breeding season, 20,000 images every minute of every day for three weeks. For penguin populations on the Antarctic Peninsula, this kind of intensive (and extensive) monitoring has shown that their numbers are overall in decline. The correct intervention to manage these declines, however, relies on understanding the main drivers – and the non-linearity – of population changes.

Dr Tom Hart in the field. Photo © Thomas Peschak.

Understanding change on the Antarctic Peninsula

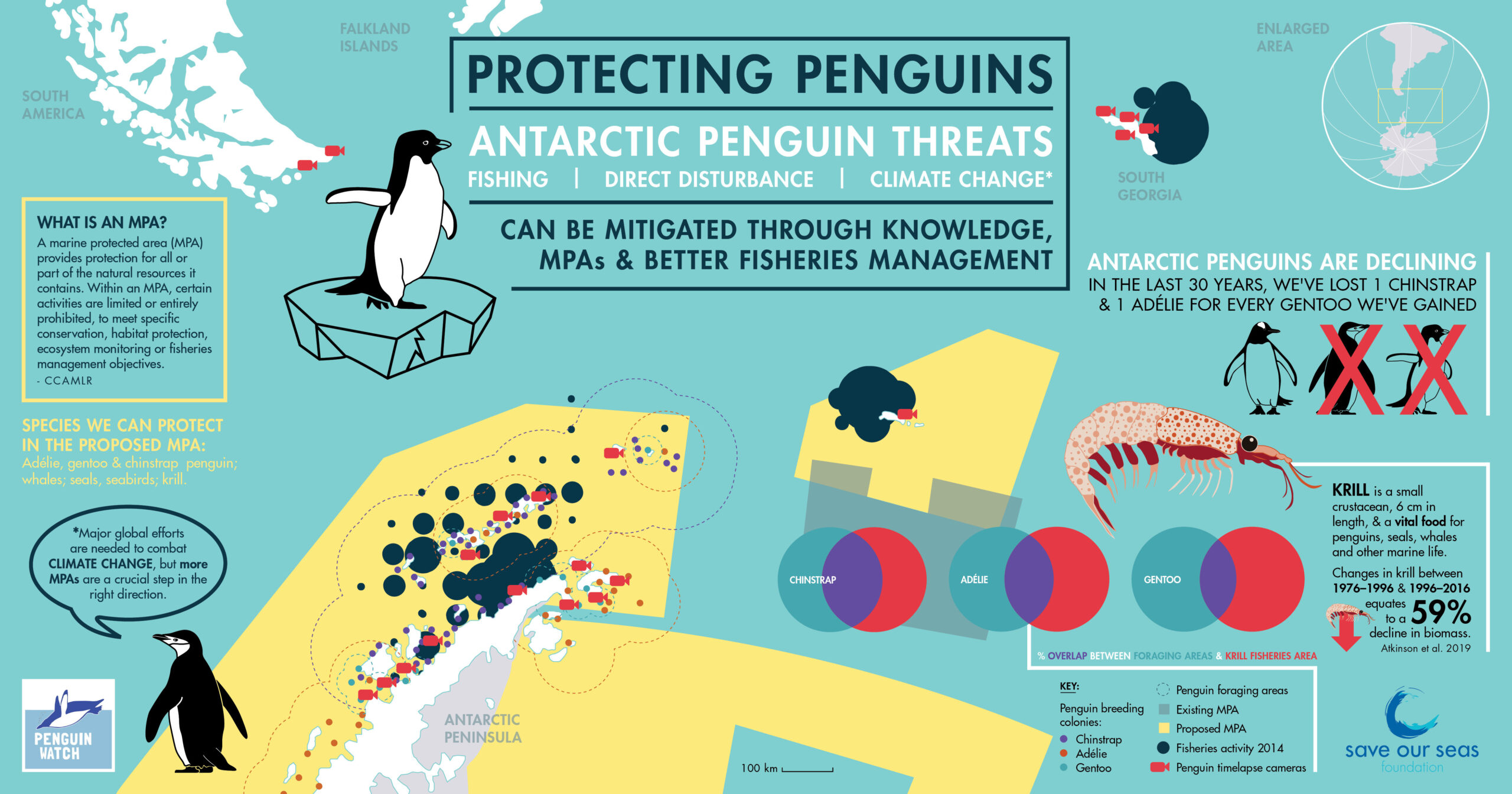

Remote as it may be, the Antarctic Peninsula has the densest human presence on the entire continent. As scientists offload from research vessels to join expeditions and set up scientific bases, tourists disgorge from visiting ships for an adventure that many of us would covet for our bucket-lists. Add to this the footprint of commercial krill fisheries that overlap with the foraging grounds of the chinstrap and Adélie penguins, the krill specialists of the Southern Ocean; a changing climate that is warming the waters around the Southern Ocean and Antarctica; and a conservation success story (but complicated ecological factor) in the return of the great whales. Together these components create a confusing (and interacting) web of stressors that might be driving penguin declines. Some areas of Antarctica and the Southern Ocean are protected in marine protected areas where human activities are regulated, but the Antarctic Peninsula currently represents a region where potential protection is still only at the proposal stage and many conflicting interests and threats to Antarctica’s biodiversity overlap.

Artwork by Rohan Chakravarty | © Save Our Seas Foundation.

By the time proposals for marine protected areas are on the table and under discussion, it is already almost too late to start collecting the kind of information that can help guide where protection is best placed around the peninsula to help halt the declines in penguin numbers and how large these areas need to be. This is where the importance of Tom’s work becomes clear: a time series of data over the course of a decade gives us the kind of insights into real trends that is needed to guide decision-making. This kind of dataset also allows us to measure how effective a marine protected area is once it’s in place, because there is an overview that shows us what the ecosystem looked like before – and after – protection measures were applied. Moreover, these data can’t be collected in limited areas; the spatial scale needs to be as big and ambitious as the time scale. To paraphrase some of what scientist Simon Levin delivered in his Robert H. MacArthur award lecture called ‘The Problem of Pattern and Scale in Ecology’, scale is essential to everything in ecology: the patterns we observe may change according to the resolution and extent of our analysis in both space and time. The trick about scale in Antarctica lies in being able to achieve it in an extreme environment where researchers might only visit single locations once a year.

Photo © Thomas Peschak.

Hacking tradition and doing things differently

The team also deploy drones and collect penguin faecal samples when they are physically on the Antarctic Peninsula. The remote camera network, however, gathers data continuously, even when the researchers are not on site. ‘For some really remote places, we are now easily getting a year’s worth of data from an hour-long initial visit,’ Tom explains. ‘If we did this the conventional way, it would mean establishing a camp or science base. That fixes the logistics in some way, because it only allows you to visit the colonies from this point. However, this method doesn’t scale. What we do know is that a lot of different sites in Antarctica are visited several times a year; they’re just not visited long enough to conduct typical science. We thought about what we could do that would facilitate remote monitoring so that our equipment could be put in place to collect good data in a meaningful way during the course of a single hour-long visit to a site.’ The result was Tom’s group’s network of cameras that have been collecting information across the Scotia Arc since 2009, with the bonus of drone footage, on-the-ground counts and faecal samples that can help them understand penguin diets, diseases and stress levels.

The question remains: how did Tom get here? He muses for a moment before rejoining with an answer that pushes the bounds of traditional practicality and scientific conservatism. ‘You really want to ask the question “How can I know everything from everywhere?” He pauses for a moment and then continues, ‘The question then becomes “If I thought on a much greater scale, how would that change what I thought and how I acted?” That line of enquiry gets us to a network of cameras very quickly.’

‘Long-term monitoring is vital and yet it’s seldom funded,’ he continues. ‘Everyone has 20/20 hindsight vision of what they know as a truth once they’ve seen it as a time series. And yet the value of these kinds of data are repeatedly underestimated. The beauty of these cameras is that they are still relatively cheap to keep going, and we had them in place before the pandemic changed things. For a start, no one really believed we could successfully leave a camera out year-round. Then the cameras survived and we didn’t need to replace them. Now, by measuring change less invasively by not visiting these areas as frequently – and by targeting areas that are not typically reached – you manage to gather a different (and fuller) research story.’

Photo © Thomas Peschak.

Conflict and complexity: disentangling drivers of change

Tom’s project with the Save Our Seas Foundation now capitalises on this bold, large-scale and long-term thinking. His aim is to continue to collect monitoring data over the course of 2020, 2021 and 2022: anomalous years that have entirely removed, or radically reduced, human presence on the Antarctic Peninsula and around the Scotia Arc. The disappointment of a lost holiday as tourism was eliminated in the Southern Ocean, and the panic of lost opportunities as many national research programmes were temporarily halted or closed, are not necessarily Tom’s to share. The pang of a lost visit to the wild landscape he loves so much is perhaps a small price to pay for the potential this project now has to measure the difference between 10 years’ worth of monitoring data and these years of human absence. In doing so, Tom and his team will be able to better tease apart the complicated web of stressors that usually overlap in space and time on the Antarctic Peninsula. Now he is able to look at a change in baseline penguin population numbers and behaviour and analyse any changes in response to climate change and fishing without the confounding factor of the stress that tourists and scientists add to the peninsula’s penguins. The team also hope to look at the overlap between commercial fishing effort and where penguins are foraging – the kind of information that will give accurate insights to policy-makers guiding the creation of a potential Antarctic Peninsula marine protected area.

Disentangling the threats faced by Antarctica's penguin populations by looking at where colonies and feeding grounds overlap with possible threats. Artwork by Nicola Poulos | © Save Our Seas Foundation

Photo © Thomas Peschak.

A future for Antarctic penguins

And so we return to the concept of anticipating change. That our world changes is a given; whether we notice, or remember that it changes, is a matter of perspective. Fisheries scientist Professor Daniel Pauly coined the concept of ‘shifting baselines’ to explain how, when we measure change in different systems, we do so in reference to earlier states – but that these ‘reference points’ that we use as comparative anchors might actually be altered in relation to an even earlier reference state. He puts it best in his TED Talk ‘The Ocean’s Shifting Baseline’ when he says, ‘We transform the world, but we don’t remember it. We adjust our baseline to the new level and we don’t recall what was there.’ When pressed for what he might have said about penguins and their populations, and about what the drivers of their declines might be, if he’d only started scrambling to measure things as the pandemic broke, Tom bursts into a spontaneous chuckle. ‘Wouldn’t have a clue!’ he says.

No one could have foreseen the Covid-19 pandemic, and certainly no one would have wished for the consequences that have rippled out across our planet. But change is a certainty, and there is clear value in being able to monitor its effects even when we are caught unawares by change’s particular guise. As Tom’s cameras continue to capture the secret lives of penguins across the Antarctic Peninsula, there is a strange kind of hope to be found in the power of the project that may emerge in the absence of our presence.