How overfishing has caused shark and ray populations to collapse

Sharks and rays are in dire need of conservation action. More than a third of their species are at risk of extinction, as their slow population growth rates make them highly susceptible to fishing pressure. Indeed, overfishing is their primary extinction threat. Now, a recent study has created the shark and ray Red List Index to track their extinction risk over time. The results are harrowing.

Shark and ray extinction risk has drastically expanded over 50 years

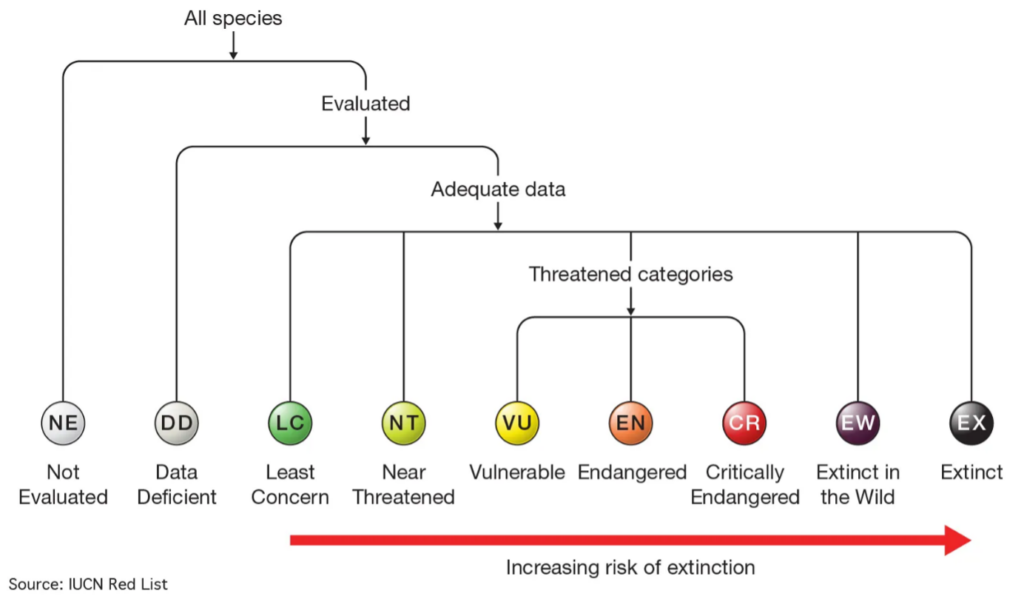

The Red List Index is a conservation indicator that uses changes in the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species over time to measure species’ extinction risk. The new study focused on 1199 shark and ray species, measuring their extinction risks with Red List status changes between 1970 and 2020, as determined by the IUCN Species Survival Commission Shark Specialist group. A whole array of experts was involved in these status assessments – including 322 assessors, 363 contributors, 118 reviewers and 180 members of the specialist group.

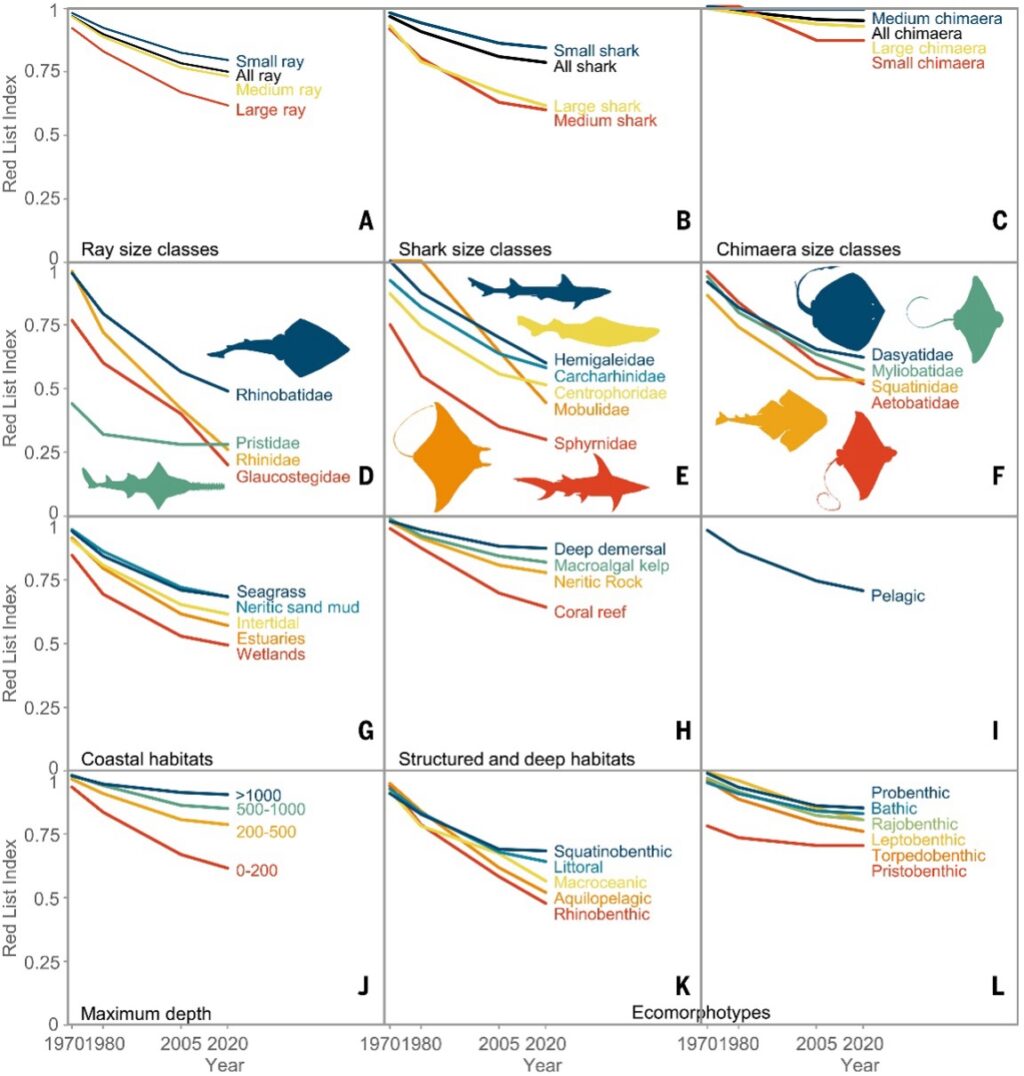

The most eye-opening finding was how sharks and rays exponentially became endangered over 50 years. In 1970, only 37 of the 1,199 species (3.5%) were threatened based on their IUCN status. By 1980, 157 species had become threatened; by 2005, 339 were threatened; and by 2020 the figure had risen to 391 – leaving 37.5% of species at risk of extinction. Global catch numbers further revealed a 50.1–56.2% reduction in abundance since 1970. In short, as well as over a third of species becoming threatened, shark and ray populations have halved in the past 50 years.

Coastal and large-bodied species have the highest extinction risk

Strikingly, the study also revealed precisely which sharks and rays are at the greatest risk of extinction.

Species living in rivers, estuaries and coastal habitats had the highest proportion of threatened species. This includes river sharks, eagle rays and benthic coastal species sensitive to trawl fishing, such as angel sharks and rhino rays; many of these have now been rendered Critically Endangered. Such a result is particularly alarming as coastal habitats harbour highly biodiverse shark and ray communities. Although deep-sea species had the smallest proportion of threatened species, it should be noted that even their populations are already substantially declining due to fishing for oil and meat. This may reflect the fact that fisheries are expanding into deeper and more open waters as inshore yields collapse.

In addition, the largest sharks and rays became threatened much more quickly than smaller species. This is most likely because large species are the most sensitive to overfishing, owing to their slow growth and inherently small population sizes. This is in line with the consensus that large-bodied species are highly associated with extinction risk in modern oceans.

Erosion of ecological roles

As the extinction risk has expanded, there will also have been a natural decline in ecological function. Although they are widely labelled as apex predators, sharks and rays actually play a wide variety of ecological roles, including nutrient transporters and lower-level predators. The range of these functions is called functional richness and is quantified using combinations of ecologically relevant traits such as body size and habitat.

Using four traits, the study projected functional losses through time as the most threatened species are lost to overfishing. The loss of all threatened species was projected to cause a 22% decline of functional richness, suggesting that shark and ray communities will lose variety in their ecological roles. Such losses are comparable to previous declines seen in the shark fossil record. Since prehistoric species never faced the threat of overfishing, with their functional changes spanning millions of years, this puts into perspective the severity of human-induced threats to sharks and rays.

Notably, the projected decline was 8% greater than expected when species losses were randomised. This indicates that threatened species are disproportionately important for maintaining functional richness, playing rare or extreme ecological roles. Among such species would be the very largest species, which have rapidly become endangered over the past 50 years. With current marine protected areas inadequately protecting elasmobranch diversity hotspots, these results further highlight the peril facing sharks and rays not just on a species level, but on a functional one too.

Photo © Simon Hilbourne

So what can we do to avert further depletion?

The alarming nature of these results, coupled with the fact that fisheries are chronically undermanaged, solutions to the crisis are urgently needed. A report published last year by the IUCN Species Survival Commission Shark Specialist group highlighted that the scale of shark and ray population declines may outstrip current conservation research and policy. For example, although spatial protections such as Important Shark and Ray Areas show promise of being manageably conserved while focusing on highly threatened species of particular habitats or life histories, they will need stricter management. Furthermore, these and other protected areas will need to be expanded to cover more hotspots of shark and ray biodiversity, and will probably have to be expanded further as climate change shifts species distributions. CITES listings are already driving national fisheries assessments and monitoring to regulate fishing, but these will need stronger enforcement, since fishing pressure is the single biggest driver of shark and ray extinction risk. Ultimately, if current protection is not strengthened, sharks and rays will continue to decline alarmingly, with devastating consequences for oceans worldwide.

**Reference

Dulvy NK, Pacoureau N, Matsushiba JH, Yan HF, VanderWright WJ, Rigby CL, Finucci B, Sherman CS, Jabado RW, Carlson JK, Pollom RA, Charvet P, Pollock CM, Hilton-Taylor C, Simpfendorfer CA. 2024. Ecological erosion and expanding extinction risk of sharks and rays. Science 386: eadn1477.